A mouse study found that dietary sugar alters the gut microbiome, triggering a chain of events that leads to metabolic diseases, prediabetes, and weight gain.

The findings, published in Cell , suggest that diet is important, but an optimal microbiome is equally important for the prevention of metabolic syndrome, diabetes and obesity.

Diet alters the microbiome

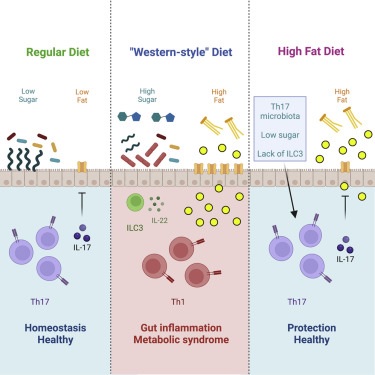

A Western-style high-fat, high-sugar diet can lead to obesity, metabolic syndrome and diabetes, but it is unknown how the diet initiates unhealthy changes in the body.

The gut microbiome is indispensable for an animal’s nutrition, so Ivalyo Ivanov, PhD, associate professor of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, and colleagues investigated the early effects of diet Western style in the microbiome of mice.

After four weeks on the diet, the animals showed features of metabolic syndrome, such as weight gain, insulin resistance, and glucose intolerance. And their microbiomes had changed dramatically, with the number of segmented filamentous bacteria, common in the gut microbiota of rodents, fish and chickens, dropping sharply and other bacteria increasing in abundance.

Changes in the microbiome alter Th17 cells

The researchers found that reducing filamentous bacteria was critical to the animals’ health through its effect on Th17 immune cells. Decreasing filamentous bacteria reduced the number of Th17 cells in the intestine, and subsequent experiments revealed that it is Th17 cells that are necessary to prevent metabolic diseases, diabetes, and weight gain.

“These immune cells produce molecules that slow the absorption of ’bad’ lipids from the intestines and decrease intestinal inflammation,” says Ivanov. “In other words, they keep the intestine healthy and protect the body from the absorption of pathogenic lipids.”

Sugar vs fat

What component of the high-fat, high-sugar diet led to these changes? Ivanov’s team found that sugar was the culprit.

“Sugar eliminates filamentous bacteria and, as a consequence, the protective Th17 cells disappear,” says Ivanov. “When we fed the mice a high-fat, sugar-free diet, they retained intestinal Th17 cells and were completely protected from developing obesity and prediabetes, even though they consumed the same amount of calories.”

But eliminating sugar didn’t help all the mice. For starters, among those lacking filamentous bacteria, removing sugar had no beneficial effect and the animals became obese and developed diabetes.

“This suggests that some popular dietary interventions, such as minimizing sugars, may only work in people who have certain bacterial populations within their microbiota,” says Ivanov.

In those cases, certain probiotics could be helpful. In Ivanov’s mice, filamentous bacteria supplements led to recovery of Th17 cells and protection against metabolic syndrome, despite the animals’ consumption of a high-fat diet.

Although people do not have the same filamentous bacteria as mice, Ivanov believes that other bacteria in people may have the same protective effects.

Providing Th17 cells to mice also provided protection and may also be therapeutic for people. “The microbiota is important, but the real protection comes from the Th17 cells induced by the bacteria,” says Ivanov.

“Our study emphasizes that a complex interaction between diet, microbiota and the immune system plays a key role in the development of obesity, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes and other conditions,” says Ivanov. "It suggests that for optimal health it is important to not only modify your diet, but also improve your gut microbiome or immune system, for example by increasing Th17 cell-inducing bacteria."