A study of more than ten million births finds that shared birth months are statistically common.

Summary The number of births varies depending on the season. Research on birth seasonality has shown that women’s birth season somewhat influences that of their children, but the factors underlying the intergenerational transmission of birth seasonality are still unknown. Using data from Spain and France, we analyzed the possibility of transmission of the season of birth between generations, checking whether relatives tended to be born in the same season. The results indicated that there was an association (a similarity) between the birth seasons of parents and children, which partially explains the stability of seasonal patterns over time. This association also existed between the birth seasons of the parents. Although the parental association is directly explained by an excess of marriages with spouses born in the same month, the general association can be explained by two facts: different sociodemographic groups show differentiated birth patterns and family members share sociodemographic characteristics. Birth season appears to be related to family characteristics, which should be controlled for when evaluating the effects of birth month on subsequent health and social outcomes. |

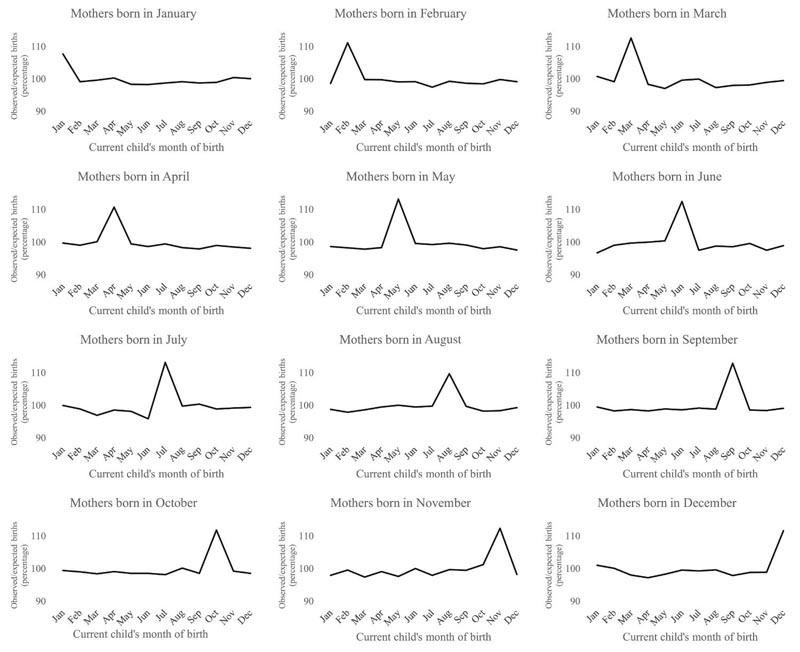

Figure: Monthly ratios of observed/expected births for the current birth months of the child and the mother, Spain 1980-83. Source: Authors’ analysis of vital statistics for Spain (National Institute of Statistics Citation2020) and metropolitan France (INSEE Citation2022).

Comments

Do you celebrate your birthday the same month as your mother? If so, you are not alone.

The phenomenon occurs more frequently than expected, according to a new study of millions of families. Siblings also tend to share each other’s birth month, as do children and parents, analysis of 12 years of data shows, while parents are also born in the same month more often than one might expect. predict.

Previous research has found that the season of birth of women somewhat influences that of their children. But this research, published in the peer-reviewed journal Population Studies , is the first to show that women are more likely to have children in the same month they are born .

Researchers from Spain and the United States analyzed official data on more than 10 million births. We searched for all births in Spain from 1980 to 1983 and from 2016 to 2019 and all births in France from 2000 to 2003 and from 2010 to 2013. The records provided the month of birth of the child, as well as that of his parents and the brother closest to them in age.

Births in a particular country tend to follow a pattern, with more babies being born at certain times of the year than at others. This is known in academic literature as birth seasonality .

But when the researchers divided the birth data into groups based on the mothers’ birth month , the births did not follow the expected pattern. Instead, there was an increase in January births among mothers who were born in January, an increase in February births among mothers who were born in February, and so on. Overall, there were 4.6% more births in which mother and child shared the same birth month than expected. This was true for both countries and all four periods studied.

This was also the case for siblings (there were 12.1% more births than expected in which adjacent siblings had the same birth month), parents with the same birth month (4.4% more births) and when a child had the same birth month as his father (2% more births).

A second, less detailed analysis of all births in Spain from 1980 to 2019 and all births in France from 2000 to 2019 confirmed the result. The phenomenon is likely to have its roots in relatives who share sociodemographic characteristics: people from similar backgrounds are known to form couples and are more likely to give birth at certain times of the year, say researchers Dr. Adela Recio Alcaide, from the University of Alcalá in Spain, and Professor Luisa N. Borrell, from the City University of New York in the United States.

In Spain, for example, a woman with higher education is more likely to give birth in spring than a woman without higher education. If she has a daughter, in addition to being more likely to be born in the spring, this daughter may be more likely to have higher education, since her mother does. And so, when this daughter has children, she will be more likely to have them in the spring as well. That is, this daughter will be more likely to have children in the same season in which she was born because she has maintained her family sociodemographic characteristics – specifically the higher educational level – that make her more likely to give birth in a certain time – spring – and , as a result, the season (and even month) of birth is passed down from generation to generation.

Factors that can affect fertility biology , such as food availability and sunlight exposure, can also vary depending on a person’s background.

“What could cause family members to be more likely to be born in the same season? The possible explanations seem to be both social and biological,” says Dr. Adela Recio Alcaide, epidemiologist at the University of Alcalá.

“The excess of children with a father and mother born in the same month seems to be due to social or behavioral causes prior to conception that are related to the choice of a partner born in the same month, as we have observed this excess with marriage statistics, spouses being more likely to mate with someone of the same month.”

"This," adds co-author Professor Luisa Borrell of the City University of New York, "may not be surprising given that things like associations tend to be made up of people with similar sociodemographic characteristics."

"In addition, biological factors known to affect birth seasonality, such as photoperiod exposure, temperature, humidity, and food availability , also depend on sociodemographic characteristics, as different social groups are exposed to these factors. to varying degrees," says Professor Borrell, a social epidemiologist in the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at City University’s Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy.

Strengths of the study include the large number of births included in the analysis and the inclusion of data from different decades and different countries. However, one limitation is that the analysis assumes "independence of the results, but that may not be the case and therefore dependence of the results within families may have affected the results." To adjust for this, the team repeated their analyzes to account for the dependence of the results within families and the results were very similar to those presented. Although this is a novel finding, more research is needed to confirm and deepen the results and their implications.

| In summary , this study has demonstrated the tendency of family members to be born in the same season. While parental similarity is directly explained by an excess of marriages with spouses born in the same month, overall similarity can be explained by different sociodemographic groups showing distinct birth patterns and relatives sharing sociodemographic characteristics. Rather than being a random variable, birth season appears to be related to family characteristics, which should be controlled for when evaluating the effects of birth month on subsequent outcomes. This study has added evidence about the dynamics underlying birth seasonality by unraveling a similarity that can only be discovered by using large sets of microdata. |