New research led by scientists at the University of Colorado Boulder suggests that the eyes really may be the window to the soul—or, at the very least, the way humans move their eyes can reveal valuable information about how they make decisions.

The vigor of saccades reflects the increase in decision variables during deliberation.

Highlights

|

Summary

During deliberation, as we calmly consider our options, neural activities representing decision variables that reflect the goodness of each option increase in various regions of the cerebral cortex.

If the options are represented visually, we make saccades , focusing our gaze on each option. Do the kinematics of these saccades reflect the state of the decision variables? To test this idea, we engaged human participants in a decision-making task in which they considered two difficult options that required walking across various distances and inclines. As they deliberated, they made saccades between symbolic representations of their options. These deliberation period saccades did not influence the effort they would exert later, but saccade velocities increased gradually and differentially: the rate of increase was fastest for saccades toward the option they later indicated as their choice. In fact, the rate of increase coded the difference in the subjective value of the two options. Importantly, participants did not reveal their choice at the end of deliberation, but instead waited for a delay period and finally expressed their choice by making another saccade. Surprisingly, the vigor of this saccade was reduced to baseline and no longer encoded subjective value. Thus, saccadic vigor appeared to provide a real-time window into the hidden process of option evaluation during deliberation.

Comments

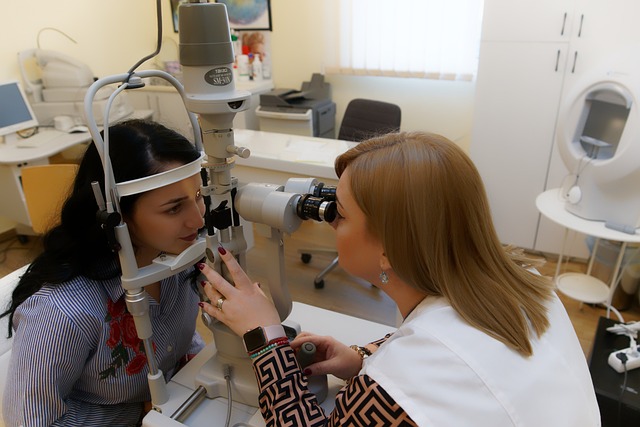

The new findings offer researchers a rare opportunity in neuroscience: the chance to look at the inner workings of the human brain from the outside. Doctors could also use the results to one day screen their patients for diseases like depression or Parkinson’s disease.

"Eye movements are incredibly interesting to study," said Colin Korbisch, a doctoral student in the Paul M. Rady Department of Mechanical Engineering at CU Boulder and lead author of the study. “Unlike your arms or legs, the speed of your eye movements is almost entirely involuntary. “It is a much more direct measure of these unconscious processes that occur in your brain.”

He and his colleagues, including researchers at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, published their findings in the journal Current Biology .

In the study, the team asked 22 human subjects to walk on a treadmill and then choose between different configurations displayed on a computer screen: a short walk up a steep incline or a longer walk on flat terrain. .

The researchers found that the subjects’ eyes gave them away: Even before making their decisions, the treadmill users tended to move their eyes faster when looking toward the options they ultimately chose. The more vigorously they moved their eyes, the more they seemed to prefer their choice.

“We discovered an accessible measure that will tell you, in just a few seconds, not only what you prefer but how much you prefer it,” said Alaa Ahmed, lead author of the study and associate professor of mechanical engineering at CU Boulder.

suspicious eyes

Ahmed explained that how or why humans make decisions (tea or coffee? dogs or cats?) is notoriously difficult to study. Researchers don’t have many tools that allow them to easily look inside the brain. Ahmed, however, believes that our eyes could give insight into some of our thought processes. She is particularly interested in a type of movement known as a "saccade."

“The main way our eyes move is through saccades,” Ahmed said. “That’s when your eyes quickly jump from one fixation point to another.”

Rapidly is the key word: Saccades typically take only a few dozen milliseconds to complete, making them faster than an average blink.

To find out if these rapid movements give clues about how humans make decisions, Ahmed and his colleagues decided to hit the gym.

In the new study, the team set up a treadmill on the CU Boulder campus. Study subjects exercised at various inclines over a period of time and then sat in front of a monitor and a high-speed camera-based device that tracked their eye movements. While on the screen, they weighed a series of options, getting 4 seconds to choose between two options represented by icons: Did they want to walk for 2 minutes on a 10% grade or for 6 minutes on a 4% grade? Once that was done, they returned to the treadmill to feel the burn depending on what they chose.

The team found that the subjects’ eyes underwent a marathon of activity in a short period of time. As they considered their options, individuals flitted between the icons, first slowly and then faster.

“Initially, saccades for either option were equally vigorous,” Ahmed said. “Then as time went on, that vigor increased and increased even faster for the option they ultimately chose.”

The researchers also found that the people who made the hastiest decisions, perhaps the most impulsive members of the group, also tended to move their eyes more forcefully. Once the subjects decided on their choice, their eyes slowed down again.

“Real-time readouts of this decision-making process typically require the placement of invasive electrodes in the brain. Having this easier-to-measure variable opens up a lot of possibilities,” Korbisch said.

Disease diagnosis

Rapid eye movements may be important for much more than understanding how humans make decisions. Studies in monkeys, for example, have suggested that some of the same pathways in the brain that help primates choose between this or that may also go awry in people with Parkinson’s, a neurological disease in which people experience tremors, difficulty to move and other problems.

“Slow movements are not only a symptom of Parkinson’s, but also appear in many mental health disorders, such as depression and schizophrenia,” Ahmed said. “We think these eye movements could be something that medical professionals track as a diagnostic tool, a way to identify the progress of certain diseases.”