Summary Theories of scientific and technological change view discovery and invention as endogenous processes in which accumulated prior knowledge enables future progress by allowing researchers to, in Newton’s words, "stand on the shoulders of giants ." Recent decades have witnessed an exponential growth in the volume of new scientific and technological knowledge, thus creating the conditions that should be ripe for breakthroughs. However, contrary to this view, studies suggest that progress is slowing in several important fields. Here, we analyze these claims at scale over six decades, using data from 45 million articles and 3.9 million patents from six large-scale data sets, along with a new quantitative metric, the CD index, which characterizes how papers and patents change Citation networks in science and technology We find that papers and patents are increasingly less likely to break with the past in ways that push science and technology in new directions. This pattern holds universally across fields and is robust across multiple different citation- and text-based metrics. We subsequently link this decrease in perturbation to a reduction in the use of prior knowledge, allowing us to reconcile the patterns we observe with the ’shoulders of giants’ view . We find that the observed declines are unlikely to be driven by changes in the quality of published science, citation practices, or field-specific factors. Overall, our results suggest that slowing rates of disruption may reflect a fundamental change in the nature of science and technology. |

Comments

The number of science and technology research papers published has skyrocketed in recent decades, but the "disruption" of those papers has declined, according to an analysis of how the papers radically depart from previous literature.

Data from millions of manuscripts show that, compared with research from the mid-20th century, research conducted in the 2000s was much more likely to advance science incrementally than to veer in a new direction and render earlier work obsolete. . Analysis of patents from 1976 to 2010 showed the same trend.

“The data suggest that something is changing,” says Russell Funk, a sociologist at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis and co-author of the analysis, which was published in Nature . “You don’t have the same intensity of revolutionary discoveries that you once had.”

Revealing quotes

The authors reasoned that if a study was highly disruptive, subsequent research would be less likely to cite the study’s references and would instead cite the study itself. Using citation data from 45 million manuscripts and 3.9 million patents , the researchers calculated a measure of disruption, called the CD index, in which values ranged from -1 for the least disruptive work to 1 for the most disruptive. .

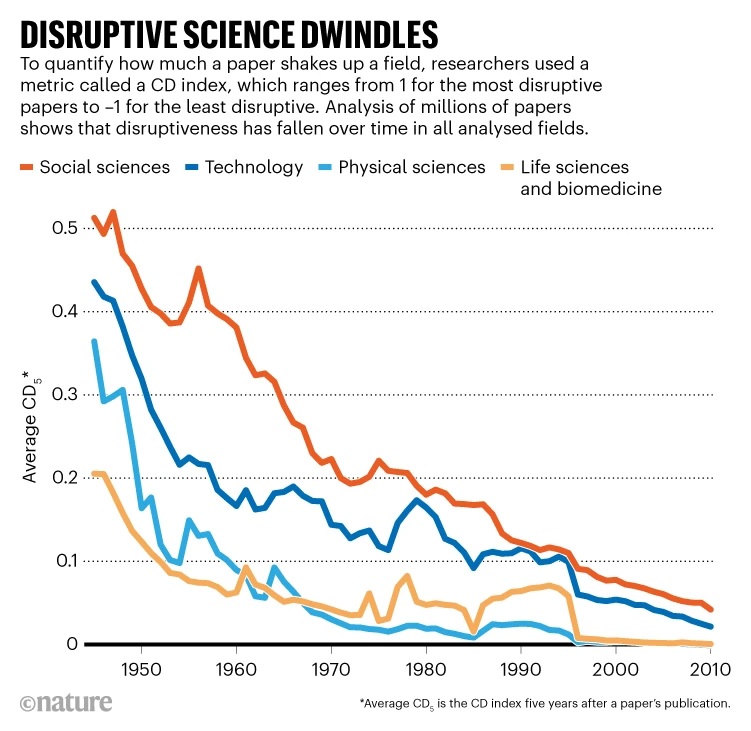

The average CD rate decreased by more than 90% between 1945 and 2010 for research manuscripts (see ’Disruptive science declines’) and by more than 78% between 1980 and 2010 for patents. Disruption decreased across all research fields and patent types analyzed, even when possible differences in factors such as citation practices were taken into account.

The graph shows that the disturbance of articles has decreased over time in all fields analyzed.

The authors also analyzed the most common verbs used in the manuscripts and found that while research in the 1950s was more likely to use words evoking creation or discovery, such as "produce" or "determine" , that carried out in the 2010s were more likely to refer to incremental progress, using terms such as ’improve’ or ’increase’ .

“It’s great to see this [phenomenon] so meticulously documented,” says Dashun Wang, a computational social scientist at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, who studies disruption in science. “They look at it 100 different ways, and overall I find it very compelling.”

Other research has suggested that scientific innovation has also slowed in recent decades, says Yian Yin, also a computational social scientist at Northwestern. But this study offers a "new beginning for a data-driven way to investigate how science changes," he adds.

Disruption is not inherently good, and incremental science is not necessarily bad, says Wang. The first direct observation of gravitational waves, for example, was revolutionary and a product of incremental science, he says.

A healthy mix of incremental and disruptive research is ideal, says John Walsh, a science and technology policy specialist at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta. “In a world where we worry about the validity of findings, it might be good to have more replication and replication,” he says.

Because?

It’s important to understand the reasons for the drastic changes, Walsh says. The trend could come in part from changes in the scientific enterprise. For example, there are many more researchers now than in the 1940s, which has created a more competitive environment and increased the risks for publishing research and seeking patents. That, in turn, has changed the incentives for how researchers do their work. Large research teams, for example, have become more common, and Wang and his colleagues have found that large teams are more likely to produce incremental rather than disruptive science.

Finding an explanation for the decline won’t be easy, Walsh says. Although the proportion of disruptive research decreased significantly between 1945 and 2010, the number of highly disruptive studies has remained almost the same. The rate of decline is also puzzling: CD rates fell sharply from 1945 to 1970, then more gradually from the late 1990s to 2010. 2000, he says.