Scientists used modern human DNA to estimate when new generations were born in 250,000 years, and the age of the parents at conception.

Human generation times in the last 250,000 years Summary The generational times of our recent ancestors can inform us about the biology and social organization of prehistoric humans, placing human evolution on an absolute time scale. We present a method to predict historical male and female generation times based on changes in the mutation spectrum. Our analyzes of whole-genome data reveal an average generation time of 26.9 years over the past 250,000 years, with fathers consistently older (30.7 years) than mothers (23.2 years). Changes in average generation times by sex have been driven primarily by changes in age at parenthood, although we report a substantial increase in female generation times in the recent past. We also found a large difference in generation times between populations, dating back to a time when all humans occupied Africa. |

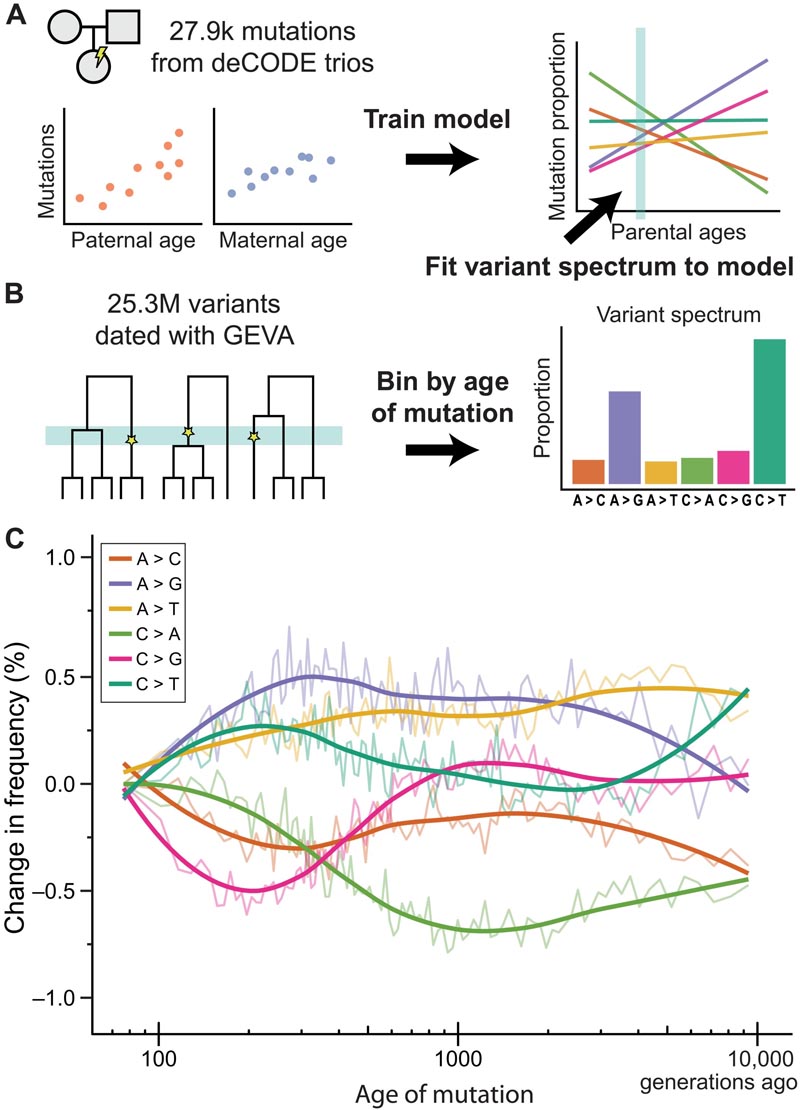

The mutation spectrum changes with human generation time. (A) Data on de novo mutations from 1,247 Icelandic trios (14) were used to train a model predicting the effect of maternal and paternal age on the mutation spectrum. (B) Data from 25.3 million segregating variants whose date of origin was estimated using GEVA (15) were used to evaluate the mutation spectrum at different periods in the past. The mutation spectrum from each time period (bin) was used as input to the model in (A) to estimate the generation interval for males and females. (C) Differences in the frequency of each of the six different types of mutation over time, compared to the most recent time period (smoothed local regression lines). Figure S15 presents the absolute frequencies of the same mutation data over time.

Comments

Men have always had children later than women throughout human history, a study suggests. The research used genetic mutations in modern human DNA to create a timeline of when people have tended to conceive children over the past 250,000 years, since our species emerged. The timeline suggests that men, on average, have conceived children about seven years later than women.

Without historical records, knowing when in their lives people had children is difficult. In recent years, sequencing technologies and large genetic data banks have allowed researchers to extract clues from DNA. But previous estimates have been limited to roughly the last 40,000 years. To look further back in time, Richard Wang, an evolutionary geneticist at Indiana University in Bloomington, and his colleagues tracked mutations that arose spontaneously in modern human DNA.

All children have new mutations that their parents do not have. These mutations arise when DNA is damaged before conception or due to random errors during cell division. Research suggests that older parents transmit more mutations than younger parents, with differences between men and women.

Mutation tracker

Wang and his colleagues used software to analyze data from a study of about 1,500 Icelanders and their parents that tracked age at conception and genetic changes across three generations. The program learned to associate certain mutations and their frequencies with the age and sex of the parents. The team then applied the newly trained model to the genomes of 2,500 modern people living around the world, to identify mutations that arose at various points in human history.

By dating when these mutations arose, the team was able to determine the average age of moms and dads over the millennia. The researchers found that 26.9 years was the overall average age of conception over the past 250,000 years. But breaking this down by sex showed that men were on average around 30.7 years old when they conceived a child, compared to 23.2 years for women. The numbers fluctuated over time, but the model suggested that men always had children later than women.

The longer generation times for men can generally be explained by the fact that men are biologically capable of having children later than women, which increases the average age of parenthood, Wang says.

Social pressure

The finding could also point to social factors , says Mikkel Schierup, a population geneticist at Aarhus University in Denmark, such as the pressure on men in patriarchal societies to build status before becoming fathers.

Population geneticist Priya Moorjani of the University of California, Berkeley, says the model does not sufficiently account for other factors, including environmental exposure, that could determine when mutations appear. This means that mutations with various causes could be unfairly attributed to the age of the parents, which could bias the results of studies like this one, Moorjani and others argued.

Although this is a valid concern, Wang says his team’s study takes into account some other factors that cause mutations. Definitively reconstructing when people became parents will require sampling more populations, Schierup says. In the meantime, this study provides "sensible estimates" that can help researchers better understand the lives of early humans, she says.