Low back pain (LBP) is the leading cause of years lived with disability worldwide. It is the second most common symptom-related reason for seeking care from a primary care provider. In 2016 in the United States, an estimated $134.5 billion was spent on health services for patients with low back and neck pain (ranked first among 154 health conditions), and this spending is increasing rapidly each year. Nonspecific low back pain is the guideline-recommended label for the vast majority of LBP cases. This refers to low back pain in which it is currently not possible to identify a specific structural cause (e.g., radiculopathy, fracture, malignancy).

The view that we cannot identify the cause of most low back pain is unpopular and therefore the label of non-specific low back pain is heavily criticized.

Opponents of the non-specific label claim that it is cumbersome to use with patients; conveys that the doctor does not know what is wrong with the patient; it does not provide a pathologic basis for low back pain and is a barrier to the provision of individualized care. In fact, the North American Spine Society (the largest spine medical society in the United States), in its 2020 clinical guideline for the diagnosis and evaluation of low back pain, appeared to reject the label of nonspecific low back pain; ’The term “non-specific low back pain” does not provide a biological basis for low back pain or aid in clinical decision making’ and ’further studies of non-specific low back pain are not warranted’ (North American Spine Society, 2020).

Doctors often use other labels to describe low back pain that is not related to a specific structural cause. For example, a survey study of 1,093 primary contact physicians found that 74% think it is possible to identify the source in all cases of low back pain and that physicians treat it differently based on the sign and symptom patterns of the suspected causes. Structural sources of low back pain, including intervertebral discs, facet joints, lumbar ligaments, and lumbar muscles. Diagnostic labels signifying pathology related to these structures are used in clinical practice. These include ’disc bulge’, ’degeneration’, ’arthritis’ and ’lumbar sprain’ . All feature prominently in disease classification systems, including the International Classification of Diseases.

Like non-specific low back pain, the use of these specific structural labels is considered problematic for three reasons:

(1) Clinical tests used to identify possible structural sources of low back pain (e.g., disc degeneration) have little validity.

(2) The actual clinical significance of these structural findings is debatable. For example, a systematic review (33 studies, 3,310 asymptomatic people) concluded that the prevalence of disc bulge was 30% in people aged 20 years, 60% in people aged 50 years, and increased to 84% in people aged 80 years. among asymptomatic people, while the prevalence of disc degeneration among asymptomatic people increased from 37% in people aged 20 years to 90% in people aged 80 years (Brinjikji et al., 2015).

(3) Some structural labels may have negative connotations and influence recovery expectations and beliefs about work and physical activity. For example, the label ’degeneration’ may convey to a patient that his or her back is fragile.

Diagnostic labels can be important as patients want an explanation for their low back pain.

However, concerns have been raised that clinicians may lack an adequate vocabulary to explain low back pain not related to a specific structural cause. It is unclear whether the current labels used for this form of low back pain reassure patients that their low back pain is not dangerous or improve the expectation of a positive outcome. Certain labels could trigger a "therapeutic misadventure . " For example, some labels (e.g., disc degeneration) may have the potential to influence patients’ desire for unnecessary lumbar imaging.

In fact, physicians often report that patient desire is a key driver of imaging ordering behavior. Unnecessary images can cause harm. Misinterpretation of imaging results by physicians could lead to unhelpful advice (e.g., taking time off work) and a cascade of medical interventions. For example, asymptomatic disc degeneration is common, and therefore unnecessary imaging could lead to overdiagnosis and overuse of ineffective and expensive treatments (e.g., lumbar fusion surgery).

Consequently, there is no strong evidence to guide clinicians’ use of different labels. Therefore, we investigated the effects of diagnostic labels for LBP on patients’ perceived need for imaging. Secondary objectives were to evaluate the effects of labeling on willingness to undergo surgery, beliefs about the need for a second opinion, perceived severity of low back pain, expectations of recovery, and beliefs about ability to participate in work. and physical activities.

Background

Diagnostic labels may influence treatment intentions. We examined the effect of labeling low back pain (LBP) on beliefs about imaging, surgery, second opinion, seriousness, recovery, work, and physical activities.

Methods

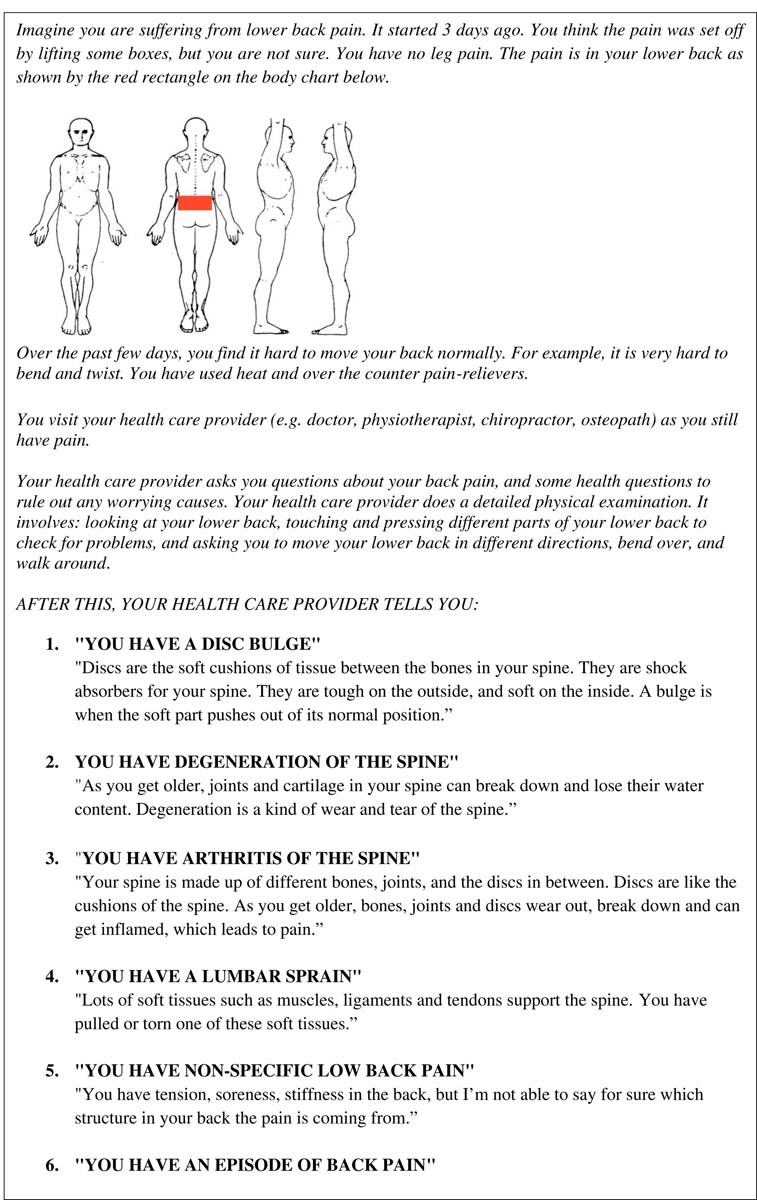

Six-arm online randomized experiment with blinded participants with and without low back pain. Participants were given one of six labels: ’disk bulge’, ’degeneration’, ’arthritis’, ’lumbar sprain’, ’non-specific low back pain’, ’back pain episode’ . The primary outcome was belief about the need for images.

Results

A total of 1375 participants were included (mean [SD] age, 41.7 years [18.4 years]; 748 women [54.4%]). Need for imaging was rated lowest with the labels “back pain episode” (4.2 [2.9]), “lumbar sprain” (4.2 [2.9]), and “non-specific low back pain” (4.4 [3.0]) compared to the labels ’arthritis’ (6.0 [2.9]), ’degeneration’ (5.7 [3.2]), and ’disc bulge’ (5. 7 [3,1]).

The same labels led to higher expectations of recovery and lower ratings of need for a second opinion, surgery, and perceived severity compared to ’disk bulge,’ ’degeneration,’ and ’arthritis.’

Differences were greatest among participants with current low back pain who had a history of seeking care. No differences were found in beliefs about physical activity and work between the six labels.

Conclusions

’Back pain episode’, ’lumbar sprain’ and ’non-specific low back pain’ reduced the need for imaging, surgery and a second opinion compared to ’arthritis’, ’degeneration’ and ’disc bulge’ among the public and patients with low back pain, as well as reducing the perceived severity of LBP and improving recovery expectations.

The impact of labels appears most relevant among those at risk for poor outcomes (participants with current low back pain who had a history of care seeking).

Summary of key findings This randomized experiment provides evidence that assignment of some diagnostic labels (back pain episode, lumbar sprain, non-specific low back pain) reduced the perceived need for imaging, surgery, and second opinion compared to other labels (arthritis, degeneration, and disc bulging) between individuals with and without LBP. Assigning the same labels (lumbar sprain, nonspecific low back pain, and back pain episode) also reduced the perceived severity of LBP and increased expectations of recovery. Importantly, the impact of labels appears most relevant among those at risk for poor outcomes (participants with current low back pain who had a history of seeking care), suggesting that what may be a benign label (e.g. ., disc bulge) among many could be dangerous/risky among the vulnerable. Interestingly, no differences were found in beliefs about physical activity and work being harmful across the six labels. This experiment suggests that certain diagnostic labels (arthritis, degeneration, and disc bulging) have the effect of encouraging testing (e.g., lumbar imaging) and treatments (e.g., surgery). |

Final message

Episodes labeled as back pain, low back sprain, and nonspecific low back pain reduced the perceived need for imaging, surgery, and a second opinion compared to disc bulge, arthritis, and degeneration among the public and low back pain patients, as well as reduce the perceived severity of low back pain and improve recovery expectations.

The impact of labels appears most relevant among those at risk for poor outcomes (participants with current low back pain who had a history of care seeking). Little or no difference was found in beliefs about physical activity and work being harmful across the six labels.

Clinicians should consider not using the labels bulging disc, degeneration, and arthritis as part of the explanations and reassurance provided to people with nonspecific low back pain. Changing the way we label low back pain may help reduce unnecessary medical testing and treatment and increase the acceptability of watchful waiting, self-management, and less intensive treatment options recommended in guidelines for the management of nonspecific low back pain. .