A somatocognitive action network alternates with effector regions in the motor cortex

Summary The motor cortex (M1) has been thought to form a continuous somatotopic homunculus extending across the precentral gyrus from the foot to facial representations despite evidence of concentric functional zones and complex action maps. Here, using precision functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) methods, we find that the classical homunculus is disrupted by regions with distinct connectivity, structure and function, alternating with effector-specific areas (foot, hand and mouth). These inter-effector regions exhibit reduced cortical thickness and strong functional connectivity with each other, as well as with the cingulate-opercular network (CON), critical for physiological action and control, arousal, errors, and pain. This interdigitation of motor effector regions and those linked to action control was verified in the three largest fMRI data sets. These results, together with previous studies demonstrating complex actions evoked by stimulation and connectivity with internal organs such as the adrenal medulla, suggest that M1 is marked by a system for whole-body action planning, the somatocognitive action network (SCAN). . In M1, two parallel systems intertwine, forming an integration-isolation pattern: specific effector regions (foot, hand, and mouth) to isolate fine motor control and the SCAN to integrate goals, physiology, and body movement. |

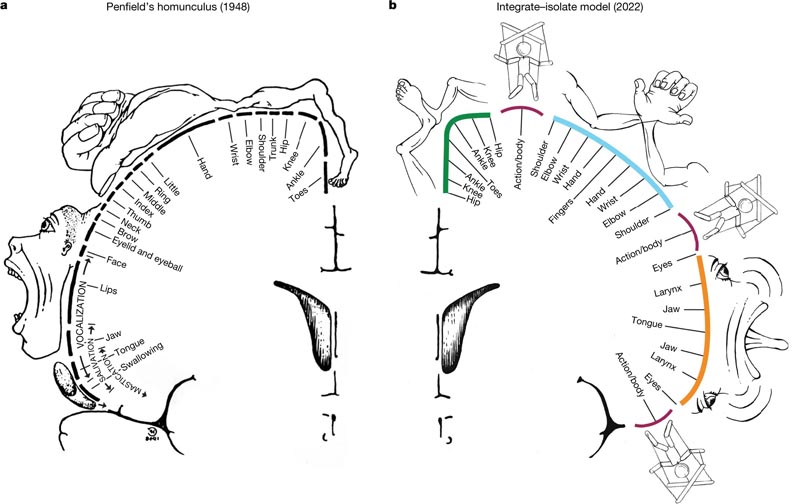

The interrupted homunculus, an integrated-isolated model of action and motor control. a, the classical Penfield homunculus (adapted from reference 2), representing a continuous map of the body in the primary motor cortex. b, In the integrated-isolated model of the M1 organization, the effector-specific functional zones (foot (green), hand (cyan), and mouth (orange)) are represented by concentric rings with proximal body parts surrounding relatively distal ones. more isolatable ( fingers, toes and tongue). The inter-effector regions (maroon) sit at the intersection points of these fields, forming part of a somato-cognitive action network for the integrative and allostatic control of the entire body. As with Penfield’s original drawing, this diagram is intended to illustrate organizational principles and should not be overinterpreted as an accurate map.

The interrupted homunculus, an integrated-isolated model of action and motor control. a, the classical Penfield homunculus (adapted from reference 2), representing a continuous map of the body in the primary motor cortex. b, In the integrated-isolated model of the M1 organization, the effector-specific functional zones (foot (green), hand (cyan), and mouth (orange)) are represented by concentric rings with proximal body parts surrounding relatively distal ones. more isolatable ( fingers, toes and tongue). The inter-effector regions (maroon) sit at the intersection points of these fields, forming part of a somato-cognitive action network for the integrative and allostatic control of the entire body. As with Penfield’s original drawing, this diagram is intended to illustrate organizational principles and should not be overinterpreted as an accurate map.

Comments

Calm body, calm mind, say mindfulness practitioners. A new study by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis indicates that the idea that the body and mind are inextricably intertwined is more than a mere abstraction. The study shows that parts of the brain area that control movement are connected to networks involved in thinking and planning, and in the control of involuntary body functions such as blood pressure and heartbeat. The findings represent a literal mind-body link in the very structure of the brain.

The research, published April 19 in the journal Nature , could help explain some puzzling phenomena, such as why anxiety makes some people want to pace; why stimulating the vagus nerve , which regulates internal organ functions such as digestion and heart rate, can relieve depression; and why people who exercise regularly report a more positive outlook on life.

"People who meditate say that by calming their body with breathing exercises, they also calm their mind," said first author Evan M. Gordon, PhD, assistant professor of radiology at the School of Medicine’s Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology. “Those kinds of practices can be really helpful for people with anxiety, for example, but until now there hasn’t been much scientific evidence of how it works. But now we have found a connection. We’ve found the place where the highly active, goal-oriented part of your mind connects with the parts of the brain that control breathing and heart rate. “If you calm one down, it should absolutely have feedback effects on the other.”

Gordon and senior author Nico Dosenbach, MD, PhD, associate professor of neurology, did not set out to answer long-standing philosophical questions about the relationship between the body and mind. They set out to verify the long-established map of the brain areas that control movement, using modern brain imaging techniques.

In the 1930s, neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield, MD, mapped such motor areas of the brain by delivering small electrical shocks to the exposed brains of people undergoing brain surgery and recording their responses. He discovered that stimulating a narrow strip of tissue in each half of the brain causes specific parts of the body to contract. Additionally, the control areas of the brain are arranged in the same order as the body parts they target, with the toes at one end of each strip and the face at the other. Penfield’s map of the brain’s motor regions, depicted as a homunculus or "little man" , has become a staple of neuroscience textbooks.

Gordon, Dosenbach, and their colleagues began replicating Penfield’s work with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). They recruited seven healthy adults to undergo hours of fMRI brain scanning while they rested or performed tasks. From this high-density data set, they built individualized brain maps for each participant. They then validated their results using three large publicly available fMRI data sets: the Human Connectome Project, the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study, and the UK Biobank, which together contain brain scans from approximately 50,000 people.

To their surprise, they discovered that Penfield’s map was not quite right. The foot control was in the place Penfield had identified. The same for the hands and face. But interspersed with those three key areas were three other areas that didn’t seem to be directly involved in movement at all, even though they were located in the motor area of the brain.

Additionally, the non-movement areas looked different than the movement areas . They appeared thinner and were strongly connected to each other and to other parts of the brain involved in thinking, planning, mental activation, pain, and the control of internal organs and functions, such as blood pressure and heart rate. Other imaging experiments showed that while non-moving areas do not activate during movement, they do activate when the person thinks about moving.

“All of these connections make sense if you think about what the brain is actually for,” Dosenbach said. “The brain is there to behave successfully in the environment so that you can achieve your goals without hurting or killing yourself. You move your body for a reason. Of course, motor areas must be connected to executive function and the control of basic body processes, such as blood pressure and pain. Pain is the most powerful feedback , right? You do something and it hurts, and you think, ’I’m not going to do that again .’"

Dosenbach and Gordon called their newly identified network the Somato (body)-Cognitive (mind) Action Network, or SCAN. To understand how the network developed and evolved, he scanned the brains of a newborn, a 1-year-old, and a 9-year-old. They also analyzed data that had previously been collected on nine monkeys. The network was not detectable in the newborn, but was clearly evident in the 1-year-old and almost adult-like in the 9-year-old. Monkeys had a smaller, more rudimentary system without the extensive connections seen in humans.

“This may have started as a simpler system to integrate movement with physiology so that we don’t faint , for example, when we stand up,” Gordon said. “But as we became organisms that do much more complex thinking and planning, the system was updated to connect a lot of very complex cognitive elements.”

Clues to the existence of a mind-body network have existed for a long time, scattered in isolated documents and unexplained observations.

“Penfield was brilliant, and his ideas have been dominant for 90 years, and they created a blind spot in the field,” said Dosenbach, who is also an associate professor of biomedical engineering, pediatrics, occupational therapy, radiology and psychological and human sciences. brain. “Once we started looking for him, we found a lot of published data that didn’t match his ideas and alternative interpretations of him that had been ignored. “We gathered a lot of different data plus our own observations, zoomed in and synthesized it, and came up with a new way of thinking about how the body and mind are linked.”

A network for mind-body integration

Two behavioral control systems are interspersed in human M1. One well-known system consists of effector-specific circuits for precise, isolated movements of highly specialized appendages (fingers, toes, and tongue), the type of dexterous movement necessary for speaking or manipulating objects. A second integrative results system , SCAN, is more important to monitor the organism as a whole. SCAN integrates body control (motor and autonomic) and action planning, consistent with the idea that aspects of higher-level executive control can derive from movement coordination. The SCAN includes specific regions of M1, SMA, thalamus (VIM and CM), posterior putamen, and the postural cerebellum, and is functionally connected to dACC regions linked to free will , parietal regions representing movement intentions, and insular regions for somatosensory processing, pain and interoceptive visceral signals.

The apparent relative expansion of SCAN regions in humans could suggest a role in complex actions specific to humans, such as coordination of breathing for speech and integration of hand, body, and eye movement for tool use. . A common factor in this wide range of processes is that they must be integrated if an organism is to achieve its goals through movement while avoiding injury and maintaining physiological allostasis . The SCAN provides a substrate for this integration, allowing for anticipatory postural, respiratory, cardiovascular and arousal changes prior to the action (such as tension in the shoulders, increased heart rate or "butterflies in the stomach" ).

The finding that action and body control merge into a common circuit could help explain why mind and body states interact so frequently .