The arcuate ligament is a fibrous arch that joins both pillars of the diaphragm to both sides of the aortic hiatus. This ligament usually runs above the origin of the celiac trunk.

Clinical vignette A 43-year-old woman was admitted with pain in the epigastrium and right upper quadrant that radiated to the back and was associated with nausea and dry heaves. The pain had started suddenly 5 days earlier. She described it as burning, pressure-like, and intermittent unrelated to food. She had no vomiting, fever, chills, changes in bowel habits, or recent unintentional weight loss. She had a history of chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease and she had had multiple episodes of this epigastric pain over the past few years, but she always thought it was related to her reflux and was never this severe. She had never undergone an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. |

- On physical examination , there was mild pain on palpation in the epigastric area. Laboratory studies were essentially normal.

- Ultrasound of the right upper quadrant showed an abnormal gallbladder and biliary tree.

- Computed tomography ( CT) of the abdomen revealed compression of the celiac artery by the arcuate ligament.

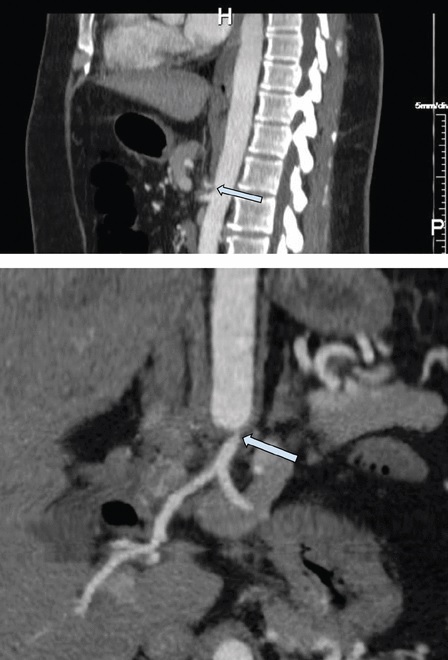

- Subsequently, a CT angiography of the abdomen was performed , which showed severe stenosis

of the origin of the celiac artery with associated soft tissue attenuation, suggestive of median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS) (Figure 1).

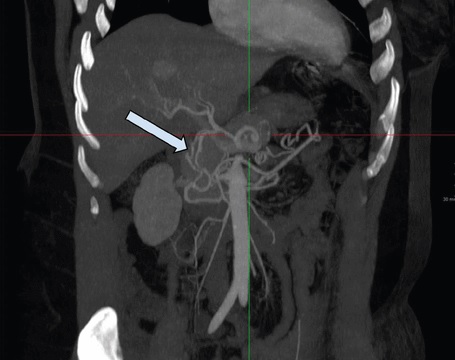

The celiac artery beyond the area of narrowing was widely patent. There were prominent arterial collaterals in the peripancreatic region, with some prominence of the gastroduodenal artery likely related to the contribution to the celiac distribution of the superior mesenteric artery (Figure 2). The superior mesenteric artery and the inferior mesenteric artery were widely patent without radiographic evidence of intestinal ischemia.

Figure 1 Contrast-enhanced computed tomography angiography, sagittal (top) and three-dimensional coronal (bottom) views, showed severe stenosis at the origin of the celiac artery (arrow) with associated soft tissue attenuation, suggestive of median arcuate ligament syndrome. .

Figure 2 Contrast-enhanced computed tomography angiography showed prominent poststenotic arterial collaterals in the peripancreatic region (arrow), with prominence of the gastroduodenal artery related to the contribution to the celiac distribution of the superior mesenteric artery, indicating that the stenosis is chronic. and hemodynamically significant.

It was unclear whether his symptoms were related to compression of the arteries or to a severe form of gastritis or peptic ulcer disease, with median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS) as an incidental finding. She was subsequently evaluated by a gastroenterologist and a general surgeon for a possible laparoscopic ligament release.

The patient’s symptoms were not typical of MALS; They were new and I had not lost weight, had no abdominal pain after eating, and had no aversion to food. The surgeon did not attribute his abdominal pain to MALS and did not recommend surgery.

The gastroenterologist recommended an upper digestive endoscopy , which showed no acute pathology to explain his symptoms and the biopsy studies were negative.

His symptoms improved during his hospital stay and he was advised to follow up with his primary care physician for further testing if necessary.

The clinical picture of median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS)

The median arcuate ligament is a fibrous arch that connects the pillars of the diaphragm that form the aortic hiatus and lie above the celiac artery. MALS, also known as Dunbar syndrome or celiac artery compression syndrome , is a rare phenomenon caused by extrinsic compression of the celiac trunk by the median arcuate ligament.

Women with MALS outnumber men by a ratio of 2:1 to 3:1, and the typical age of onset is in the fourth and fifth decades . The history and physical findings are often nonspecific. The most common clinical manifestation is chronic epigastric abdominal pain , most often postprandial or exercise-induced.

Other symptoms include nausea, vomiting, bloating, weight loss, and fear of pain caused by eating, leading to avoidance of food. Physical examination may reveal epigastric tenderness or a murmur that is amplified with expiration, but these are nonspecific.

What causes epigastric pain?

Theories regarding the pathophysiology of epigastric pain associated with MALS include foregut ischemia due to compressed celiac artery, midgut ischemia due to vascular steal syndrome, and overstimulation of the celiac plexus with subsequent vasoconstriction and splanchnic ischemia. Recently, ideas about the etiology of MALS have shifted from a vascular disease to a neurogenic disorder with compression of the surrounding celiac plexus and ganglion.

MALS Imitations

MALS resembles several other abdominal disorders in its symptoms, presenting a diagnostic challenge for the clinician. It may be confused with gastroparesis, gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, hepatitis, cholecystitis, biliary dyskinesia, appendicitis, chronic pancreatitis, colorectal malignancy, or chronic mesenteric ischemia secondary to atherosclerotic disease.

Most patients undergo extensive workup for other diagnoses with abdominal ultrasound, abdominal CT, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, and hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid scintigraphy.

MALS is considered a diagnosis of exclusion and can coexist with other intra-abdominal pathologies and be a confounding factor.

CT angiography , magnetic resonance angiography , and abdominal duplex ultrasound during deep inspiration and expiration are the most common diagnostic studies for MALS. The increasing use of CT in the evaluation of abdominal pain has led to a more frequent diagnosis of MALS.

Additionally, many asymptomatic patients have radiographic evidence of celiac compression, and mild compression can usually be seen during expiratory CT angiography; Inspiratory imaging can confirm that the narrowing is real.

Petnys et al demonstrated that 3% of patients without symptoms have celiac artery compression on CT angiography. In a retrospective study, Heo et al demonstrated that 87% of patients with MALS were asymptomatic and the disease was diagnosed incidentally by CT.

Anatomically, up to 24% of the population may have celiac artery compression; however, less than 1% of them have symptoms.5

To improve the benefit of surgical intervention, studies aimed at improving the ability to reliably diagnose MALS are required. Surgery should be reserved for patients who would benefit from it, and patient selection remains a challenge as there is a relatively poor correlation between radiographic findings of celiac artery compression and the presence or severity of symptoms . It is generally accepted that asymptomatic or accidentally discovered MALS does not warrant intervention.

- Laparoscopic arcuate ligament release has become a widely accepted treatment.

- Endovascular therapy may also be necessary, given the possible recurrence of the stenosis.

Multidisciplinary evaluation by a general surgeon, vascular surgeon, radiologist, and gastroenterologist is useful.

Cienfuegos et al offered the following selection criteria for laparoscopic treatment:

- Young woman.

- Intense postprandial pain.

- Trunk stenosis greater than 70%.

- Development of collateral circulation.