Case 1 A 68-year-old man with a history of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH) and hypertension (HTN) presented to the emergency department with fatigue, subjective fevers lasting two days, and dysuria. He supports myalgia and lumbar discomfort. He denies any recent surgeries, procedures or antibiotic use. He had an episode of nonbloody, nonbilious vomiting prior to his arrival. The patient reports that his blood sugar levels at home today were 273 and 315. He is currently complaining of bladder pressure and has not urinated in 6 hours. He is tachycardic and febrile. What should be considered in the differential diagnosis? What tests should I ask for? What imaging studies might be helpful? Case #2 An 82-year-old man with a history of BPH, HTN, diabetes, coronary heart disease (CHD), and vertigo presents to the emergency department with weakness. His wife reports that his urologist performed a procedure a few days ago, but she is not sure of his name. Today he has been vomiting and seems dehydrated. The patient has been lying in bed since yesterday, but is normally quite active with a walker. They have a big trip planned for tomorrow and are wondering if they should cancel it. Vital signs include HR 90, BP 105/76, RR 13, temperature 38.4 C, SatO2 98% in RA. |

What should you look for on the exam? What medications should I prescribe? Does the patient need to be hospitalized?

What is prostatitis?

Prostatitis can be divided into several subcategories:

| Category | Description |

| Acute bacterial prostatitis | • Severe prostate symptoms • Acute UTI • Systemic infection |

| Chronic bacterial prostatitis | • +/- symptoms of prostatitis • Recurrent UTI due to the same organism with no specific duration, but patients typically have symptoms for 3 months or more. |

| Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome | • Negative for UTI, but with voiding symptoms • Symptoms include sexual dysfunction, pelvic pain, and voiding difficulties for more than three months • Divided into inflammatory and non-inflammatory subcategories |

| Asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis | • Prostatic inflammation without genitourinary symptoms |

For the purposes of this article, we will focus on acute bacterial prostatitis.

Prostatitis syndromes are relatively common, especially in the nonelderly population. The estimated prevalence of all prostatitis syndromes is 8.2%. For patients under 50 years of age, it is the most common urological condition and for older patients, the third most common diagnosis.

In men with at least one previous episode of prostatitis, their cumulative probability of having another episode of prostatitis was 50% in patients aged 80 years and increased with age. The exact incidence and prevalence of acute bacterial prostatitis is unknown in the emergency department setting, but it is estimated that acute bacterial prostatitis contributes to 4-10% of overall prostatitis cases seen in the community.

One of the feared complications of acute bacterial prostatitis is prostatic abscess, a localized accumulation of purulent fluid within the prostate. The highest incidence of prostate abscesses occurs in men between 50 and 60 years old.

The incidence of prostate abscess in men with asymptomatic HIV and AIDS is 3% and 14% respectively. Men undergoing a urological procedure such as prostate biopsy are another notable group, with approximately 10% of these patients developing prostate abscesses.

How is prostatitis caused?

Although the prostate has natural mechanisms to help prevent infection, including immunological (antibacterial secretions) or mechanical (ejaculation and evacuation to clean the prostatic urethra), insufficient drainage or urinary reflux from the urethra or bladder into the prostate can cause stones, fibrosis or inflammation.

Seeding can also occur by inoculation after procedures involving the urethra and prostate.

Acute bacterial prostatitis is probably caused by a urinary infection ascending to the intraprostatic ducts.

The organisms involved in prostatitis may also have higher levels of certain virulence factors compared to simple cystitis or other genitourinary infections.

What are the risk factors for developing prostatitis?

| Category | Example |

| Concurrent genitourinary infections | Cystitis Urethritis Epididymitis |

| Mechanical obstruction Neurophysiological abnormalities | Urethral stricture Phimosis |

| Instrumentation | Chronic Foley catheter use Intermittent bladder catheterization Condom catheter Prostate biopsy Cystoscopy |

| Immunosuppression | HIV |

| Others | Receptive anal intercourse |

Other risk factors have been mentioned in the literature: trauma, withdrawal and dehydration, but high-quality evidence to support this is lacking.

What organisms cause prostatitis?

Similar to genitourinary infections, gram-negative bacteria are the most common cause. E. Coli constitutes the vast majority (up to 88% of cases of acute bacterial prostatitis). Other species of Enterobacteriaceae such as Klebsiella and Proteus constitute approximately 10-30% of known cases. Less commonly, Pseudomonas and other Enterococcus are involved.

Other organisms, specifically gram-positive cocci such as Staphylococcus aureus , should also be considered, as experts believe the prevalence is increasing. Bacteremia from Staphylococcus aureus infections can acutely infect the prostate. This should also warrant investigation of an occult infection in another location, such as endocarditis, soft tissue, or a vascular catheter.

> Special populations

People with recent prostate procedures may be more likely to be infected by fluoroquinolone-resistant bacteria and Pseudomonas , probably due to the use of prophylactic antibiotics. Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae can also be seen in sexually active patients, regardless of the patient’s age.

In addition to common bacterial pathogens, HIV patients may also have Salmonella typhi or Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Travelers to Asia and Australia may have Burkholderia pseudomallei , which has also been linked to the development of prostate abscesses. Immunocompromised individuals, such as patients with diabetes or HIV, are more likely to develop prostate abscesses.

Clinical presentation of acute bacterial prostatitis

Classically, patients with acute bacterial prostatitis will present with fever and constitutional symptoms in addition to urinary discomfort such as urge incontinence or hesitancy. They may also report cloudy urine and genitourinary pain.

Other patients may simply present with flu-like symptoms (nausea, weakness, chills), so taking a good history is essential to ensure you don’t miss this diagnosis.

> Physical examination

When approaching the physical examination in male patients with genitourinary complaints, physicians should be sure to visually inspect the perineum and genitals, palpate masses or other abnormalities, and perform a digital rectal examination.

The prostate is usually tender, edematous and soft on digital rectal examination, with a sensitivity of 63.3% and a specificity of 77.7%. Other sources report that more than 95% of patients have prostate tenderness on examination.

Fluctuation may suggest an abscess , with a wide incidence of 16-88%. In some cases, this is all that is needed to establish the diagnosis. Prostate massage is not recommended, but palpation of a soft prostate itself is generally safe.

Palpation of the abdomen to investigate bladder distention or flank tenderness may also be helpful when considering other diagnoses. There may also be spasm of the rectal sphincter.

> Laboratory and imaging studies

Although definitely not necessary to confirm the diagnosis, patients may have leukocytosis and elevated inflammatory markers such as ESR or CRP. Currently there are no quantitative studies that evaluate its role in the diagnosis of acute bacterial prostatitis. Serum PSA is generally not available in the emergency department and is of limited usefulness in the acute phase of the disease.

Urinalysis may be important for bacteria and pyuria. The results of midstream culture along with Gram stain are also useful in determining the responsible microbe. (Canadian Urological Association: Level IIA Recommendation).

Urine testing before and after prostate massage has been used to diagnose chronic prostatitis, but prostate massage is contraindicated in acute bacterial prostatitis due to the possibility of causing bacteremia.

One study determined that nitrite sensitivity was 55-58% and leukocyte esterase 81-83% in patients with acute bacterial prostatitis. Testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia should be considered in sexually active patients. Unless patients have valvular disease, suspected endocarditis, or sepsis, routine blood cultures are not necessary.

Bottom line: Prostatitis is a clinical diagnosis! Urine analysis and culture may be negative, so be sure to consider the broader clinical picture.

Imaging studies are usually not necessary unless there is a high suspicion of prostate abscess or the patient is high risk, with ultrasound and CT being the possible imaging modalities (Canadian Urological Association: Level IIIB/IIA recommendation).

Transrectal ultrasound is recommended first-line as a cheap imaging modality compared to other alternatives, with a sensitivity of 80-100% for prostate abscesses.

However, this modality is contraindicated in patients with intense pain, fistulas and severe hemorrhoids. This approach also has the benefit of a therapeutic intervention such as needle aspiration, with one case series reporting a success rate of 86%.

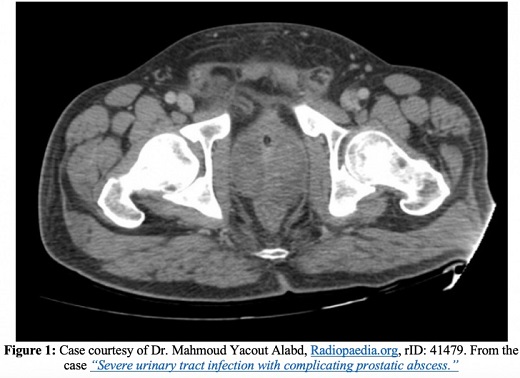

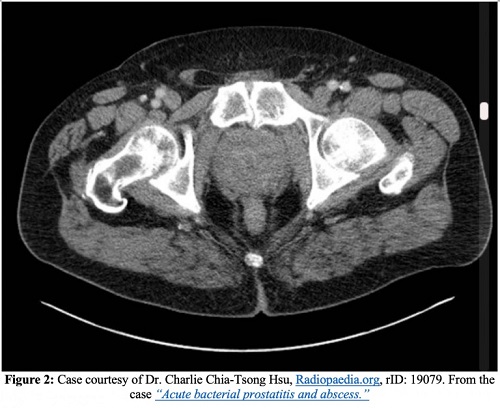

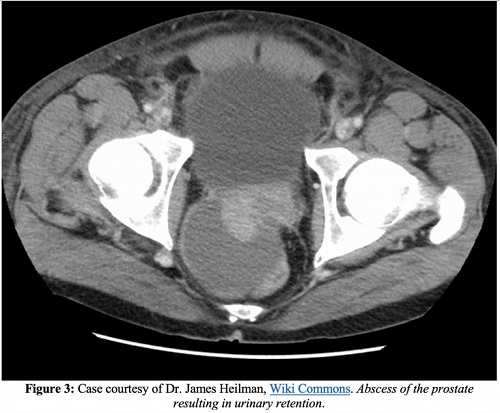

Computed tomography with and without intravenous contrast may be useful in determining the extent of disease, that is, in relation to necrotizing spread, and is the preferred imaging modality for evaluating emphysematous prostatic abscesses.

There are no recent studies that evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of CT in the diagnosis of prostatitis or prostatic abscesses. Although MRI has a higher sensitivity than CT, it has not been shown to be better than transrectal ultrasound.

Complications

In addition to endocarditis, epididymitis, further spread of infection to bone or joint spaces, and the development of chronic prostatitis, one of the most serious complications of acute prostatitis is a prostate abscess. On CT images, prostate abscesses appear as nonenhancing collections of fluid. Prostatic abscesses will appear as anechoic or hypoechoic areas on transrectal ultrasound.

Urological evaluation for possible drainage of the abscess may be required if the prostate abscess continues after at least one week of antibiotics, in certain refractory patients, or in those who have failed treatment.

Acute urinary retention is a known complication of acute prostatitis. Some sources recommend foregoing Foley catheter insertion in favor of suprapubic catheterization due to the potential risk of abscess rupture or septic shock. Others recommend a one-time catheterization with a voiding test or a short-term small-bore foley urethral catheter. Consultation with urology is recommended.

Differential diagnosis

Perhaps the most important alternative diagnosis is a UTI. Remember that instrumentation through recent procedures or anatomical abnormalities such as stricture or BPH can predispose people to developing urinary tract infections and therefore prostatitis.

Patients who do not respond to treatment of acute cystitis should be evaluated for possible prostatitis. While patients with BPH may report urinary symptoms, they should not have fever or other infectious findings on their laboratory evaluation. Prostate tenderness can help differentiate prostatitis from other diagnoses such as epididymitis or urethritis.

Management and treatment

The mainstay of treatment for uncomplicated acute bacterial prostatitis is antibiotics .

When should patients be admitted?

Patients without findings of hemodynamic instability, suspicion of impending sepsis, significant comorbidities, and tolerance to oral medication can be safely treated as outpatients with outpatient urologic follow-up.

Patients who are unreliable, without good follow-up or with a high suspicion of bacteremia should be hospitalized. Finally, patients who develop acute urinary retention should be closely monitored as they may require bladder catheterization and subsequent hospitalization.

What is the best antibiotic to use?

Although there is no evidence from comparative trials, local resistance patterns and antibiograms should be taken into account. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole should not be used as a first-line agent if regional resistance to E. Coli is greater than 10-20%.

Fluoroquinolones have higher cure rates, but consider side effects and possible adverse reactions in your patients. Choose treatment based on the most likely organism, which for most people means gram-negative coverage is key.

| Antibiotic regimen | |

| Outpatient | • Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (DC) PO every 12 hours* • Ciprofloxacin 500 mg PO every 12 hours • Levofloxacin 500 mg PO every 24 hours |

| Sexually active | • Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM x 1 dose + doxycycline 100 mg PO twice daily for 14 days |

| Hospitalized patients | • Ciprofloxacin 400 mg IV twice daily or levofloxacin 750 mg IV daily +/- gentamicin or tobramycin 5 mg/kg IV daily • Beta-lactam (e.g. piperacillin/tazobactam 4.5 g IV every 6 hours or ceftazidime) +/ - gentamicin IV or tobramycin 5mg/kg IV per day |

| Fluoroquinolone-resistant | • Ertapenem 1 g IV per day • Ceftriaxone 1 g IV per day • Imipenem 500 mg every 6 hours • Tigecycline 100 mg IV x 1 dose, then 50 mg every 12 hours |

| Bacteremia or prostatic abscess | • Ciprofloxacin 400 mg IV twice daily • Levofloxacin 500 mg IV every 24 hours • Ceftriaxone 1-2 g IV per day + levofloxacin 500-750 mg • Ertapenem 1 g IV per day • Piperacillin-tazobactam 3.375 g IV every 6 hours |

Consider adding an aminoglycoside if the patient recently took antibiotics or appears septic. Tetracyclines and macrolides have been reviewed in the literature, with limited success compared to the agents mentioned in the table.

There is some controversy regarding the ideal duration of therapy, with sources ranging from two to six weeks . Clinically, patients should begin to feel better with remission of fever and dysuria within the first week of antibiotic treatment.

Other considerations

Patients who have never used alpha blockers and who have recently been diagnosed with acute bacterial prostatitis may have symptomatic improvement when adding these to their treatment regimen. Although the urological literature maintains that alpha blockers can improve patient symptoms for all types of prostatitis, this is based on different levels of evidence.

There are no specific trials related to acute bacterial prostatitis and data are limited. Other decisions about which alpha blockers and at what doses can be taken in conjunction with the urology service. NSAIDs may also be of some use.

Case 1

The patient’s physical examination is notable for prostate tenderness and suprapubic tenderness to palpation. There is no pain on palpation of the costovertebral angle, which makes pyelonephritis less likely. He has no testicular pain, making epididymitis and torsion less likely. He has no murmurs, rubs, or gallops on cardiac examination, making endocarditis or valvular disease less likely.

After ordering a urinalysis with reflex culture, complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, an ultrasound is performed showing > 500 mL of urine. After speaking with Urology, a small urethral Foley catheter is placed with resolution of the obstruction. Urology recommends admitting the patient and monitoring clinical improvement for 24 hours before requesting a new ultrasound. The patient is started on piperacillin/tazobactam and gentamicin and improves shortly thereafter.

Case #2

On examination, the patient is actively vomiting. He has dry mucous membranes, but no generalized abdominal discomfort. It has great sensitivity to palpation of the prostate without macroscopic blood or other abnormality. His lungs are clear and he has no skin findings to suggest infection. Due to concern for sepsis, a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, lactate, blood cultures, urinalysis with antibiogram, and fluid replacement are ordered.

The patient is started empirically on ertapenem and a CT scan is ordered to evaluate for possible prostatic abscess. After resuscitation, the patient’s condition improves and, fortunately, the imaging study shows no fluid accumulation. Urology is consulted about the patient and he is admitted to the medical clinic service.

Key points

|