| Highlights |

|

The term “pneumoconiosis” is used to describe a set of occupational lung diseases associated with the inhalation of an agent (dust, smoke, fiber) in which retention in the lung is a key causal factor. The concept is most commonly applied to coal workers’ pneumoconiosis (CWP) and silicosis, but other substances are involved. They generally develop in susceptible individuals after many years of relevant industrial exposure and may progress after exposure ends.

The ability of different types of trapped particles to cause lung damage varies widely; For example, silica dust is highly fibrogenic, while iron oxide dust is much less so. This depends on the size and toxicity of the inhaled particle, as well as the lung’s ability to eliminate it.

Only a proportion of similarly exposed workers develop pneumoconiosis, suggesting that genetic factors could be relevant.

For most forms of pneumoconiosis, there are no specific therapies available, so prevention of exposure and early detection of the disease are of utmost importance.

This article focuses on the main causal exposures responsible for pneumoconiosis in the UK ( coal, silica, asbestos ). Other causes may be iron oxide, tin oxide or beryllium.

| Coal worker pneumoconiosis |

> Epidemiology

The incidence of CWP has decreased in recent years, which has been associated with a decrease in coal production. The risk of CWP is related to the duration and level of exposure, as well as the range (carbon content) of the coal.

> Clinical characteristics

Coal worker’s simplex pneumoconiosis is associated with small rounded nodules predominantly in the upper zones of the lung, representing collections of dust-laden macrophages that are visible on a chest x-ray. In the absence of coexisting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), simple CWP generally has no symptoms, physical signs, or abnormal physiology.

Complicated coal worker pneumoconiosis is associated with slowly progressive mass formation in the upper lobe and fibrosis (previously called progressive massive fibrosis). Complicated forms commonly express cough, difficulty breathing, and, in certain cases, progression to hypoxia and right heart failure.

> Research

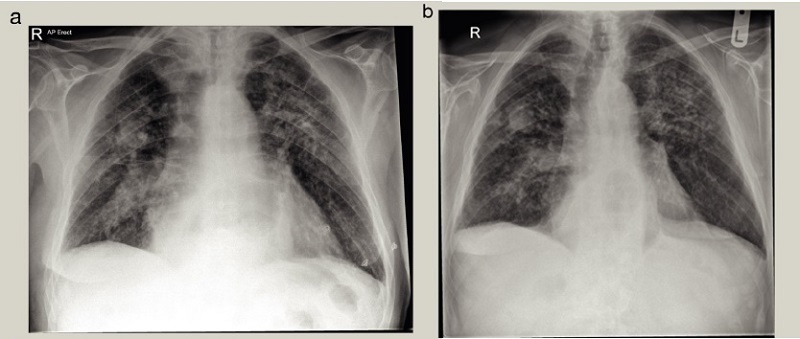

The diagnosis of simple or complicated CWP is based on typical radiological findings and occupational history of adequate exposure to coal dust. If available, prior radiology is particularly useful if it shows relatively stable appearances over many years ( Figure 1 ).

When radiological features are not typical, particularly if there is a significant smoking history, patients with pulmonary nodules and mass lesions should be discussed with the multidisciplinary lung cancer team.

In CWP, both rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody may be present in the serum, although neither is sensitive enough to be useful in diagnosis.

> Management and prevention

There are no effective medical treatments for CWP, other than management of hypoxia and right heart failure. Coal dust is also a cause of COPD and coexisting airway obstruction should be treated. The importance of quitting smoking should also be highlighted. Identifying simple CWP through health surveillance and reducing further exposure is key, in an attempt to prevent complicated diseases.

Figure 1 . Typical chest x-ray appearances of complicated coal worker pneumoconiosis. (a) Multiple small and dense nodules are seen in both the upper and middle areas, with an opacity of 3 cm in the right middle area. (b) Radiographic appearances remained relatively stable over a 4-year follow-up period.

| Silicosis |

> Epidemiology

While the incidence and mortality of silicosis has remained relatively stable in Britain over the last decade, this is in contrast to certain developing countries where it is the most common form of occupational lung disease. Several occupations are associated with exposure to respirable crystalline silica (RCS), most commonly through exposure to rocks, stones, or sand.

> Clinical characteristics and investigations

Exposure to respirable crystalline silica (RCS) can lead to a number of different disease patterns, with different rates of progression and prognoses.

Chronic silicosis usually results from at least 10 years of exposure to low-level RCS.

Simple silicosis is usually asymptomatic and is often found on a routine chest x-ray. As with CWP, simple disease can progress to complicated disease, with significant respiratory disability.

Accelerated silicosis may develop after a shorter period (usually 5-10 years) of higher level of exposure to RCS. Progression is faster than in chronic disease, the lung disease being more diffuse and the prognosis significantly worse.

Acute silicosis is associated with immediate lung damage from massive exposure to RCS over a period of weeks or months, commonly from hard rock tunneling or sandblasting. It has a very poor prognosis, and is usually fatal within a few months of presentation.

> Management and prevention

As with CWP, there is no specific treatment for silicosis, so prevention or early detection of the disease is vital. Complications such as right heart failure, coexisting airway disease, mycobacterial infection, and autoimmune diseases should be managed conventionally. Additionally, advice to quit smoking is key.

| Asbestosis |

> Epidemiology

“Asbestosis” is the term used to describe diffuse pulmonary fibrosis caused by inhalation of asbestos fibers. Unlike other types of pneumoconiosis, mortality from asbestosis in Britain is increasing. The use of asbestos has been banned in many developed countries, but occupational exposure can still occur when disturbing materials containing this substance in old buildings. Globally, asbestos production is falling.

> Clinical characteristics

It generally occurs in susceptible individuals several decades (10-20 years) after prolonged occupational exposure. People most at risk include workers directly involved in the production of asbestos materials.

The clinical features of asbestosis are similar to those of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), with cough and progressive respiratory distress with exertion. Physical examination usually reveals fine inspiratory crackles, and if present, clubbing appears to indicate a worse prognosis.

> Investigations

Diagnosis is usually based on radiological findings and an appropriate history of chronic occupational exposure. It is important to note that high-resolution CT findings may be identical to those of IPF, and a diagnosis of asbestosis should not be made or ruled out based on the presence or absence of pleural plaques. Asbestos bodies can be identified in sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, and their presence may aid in diagnosis.

> Management

It generally progresses relatively slowly. There are no specific treatments other than right heart failure treatment and smoking cessation counseling.