| Highlights |

- The field of cognitive aging has progressed and is focusing on factors that explain individual variability in performance, identifying mechanisms that lead to variation in intellectual aging, and examining ways to intervene to improve cognition or prevent decline. - Cardiovascular and metabolic health explain significant individual variation in the trajectory of cognitive aging. - Physical activity unequivocally affects cognitive and brain outcomes, and this influences perceptions of cognitive aging; That is, the rate and magnitude of decline could be manageable by engaging in healthy behaviors such as physical activity. |

| 1. Introduction |

Is cognitive decline an inevitable consequence of aging? There is overwhelming evidence of this. But is there any reason for hope and optimism in the face of this evidence of loss and decline? A narrow view of aging as decline is an exceptionally superficial perspective that masks the complexities in the topic.

The fact that there is significant individual variability in cognitive aging is irrefutable. It is quite clear that some older adults show very gradual or minimal attrition, while others show more rapid losses, regardless of clinical diagnosis. An important theoretical and empirical focus of content research has been to try to understand this personalized instability.

Once we have identified the factors that explain individual differences in neurocognitive aging, what should happen next under our research lens? The answer to this question could be that once researchers have identified the factors that explain individual variation, whether genetic factors or life experiences and exposures, there could be clearer paths to prescribing people to engage in personalized behaviors. to reduce your chances of showing intellectual losses and to maintain higher levels of productivity for longer.

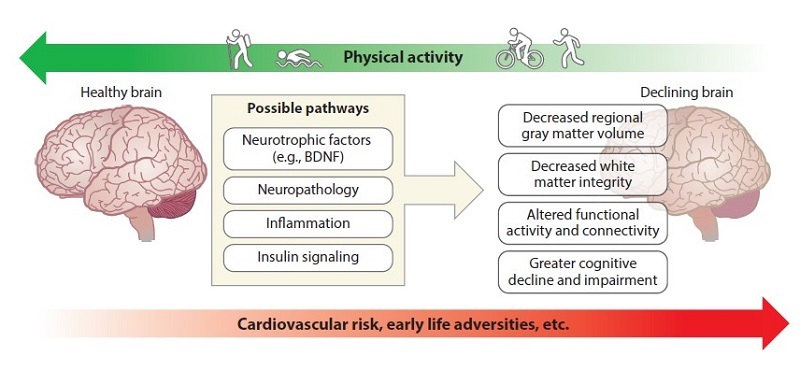

This review focuses on several factors that explain personal variation in age-related cognitive decline. Physical activity is used as an example of a goal that not only appears to analyze the situation, but is also a highly accessible intervention to improve neurocognitive function in late adulthood (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A conceptual diagram showing that cardiovascular risk and early life adversity increase the risk of more accelerated declines in cognitive aging, while physical activity has the opposite pattern, possibly reversing the same mechanisms. The biological processes of physical activity may include increased production of some molecules (i.e., BDNF) or decreased expression or accumulation of other molecules. Abbreviation: BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor.

| 2. Impact of physical health on neurocognitive aging |

Advances in the fields of human neuroscience and health psychology have reaffirmed that there is a dynamic reciprocal relationship between the brain and the body and that the health of one directly influences the health of the other. This observation has fueled the emergence of the field of health neuroscience, which leverages conceptual frameworks and methodologies from multiple disciplines (e.g., health psychology, cognitive neuroscience) to better understand how the brain works.

An interesting implication of the conceptual framework adopted by health neuroscience is that behavioral interventions known to improve physical health outcomes may also be effective in promoting healthy brain aging.

A prospective longitudinal study of brain health indicated that adults who had a greater number of protective factors for cardiovascular health exhibited fewer white matter lesions and strokes and greater overall brain volume at follow-up, suggesting brain aging. healthier. Therefore, maintaining cardiovascular health throughout life is associated with preserving brain health and may prevent or delay the onset of age-related cognitive decline.

In contrast, indicators of poor cardiovascular and metabolic health, such as hypertension, obesity, and type 2 diabetes (T2D), have been linked to negative brain health outcomes, especially in later life. Hypertension has been established as one of the main risk factors for cognitive decline and dementia due to related damage to the cerebral vasculature.

The cognitive domains that appear to be most consistently associated with hypertension include memory and executive functions, which are cognitive domains that show the earliest and most precipitous declines with advancing age. They are also two of the domains that show the greatest improvement after adopting regular physical activity.

Although obesity is a risk factor for poor cardiovascular and metabolic health, excess adipose tissue is associated with dementia risk independently of cardiovascular risk. Even in the absence of overt neurological disease, midlife obesity is prospectively associated with poorer performance on tests of general cognition, memory, attention, and executive functioning.

Similarly, T2D has been shown to accelerate cognitive aging and increase vulnerability to the development of neurological diseases. It is estimated that people diagnosed with T2D in middle age have a 50% increased risk of dementia later in life. T2D is also prospectively associated with impairments in memory, attention, and executive functioning relative to people without T2D. There is some evidence that declines in cognitive performance in T2D are accompanied by changes in brain structure and function.

Insulin resistance, a precursor to the development of T2D, has also been shown to affect cognitive performance, suggesting that poor glycemic control is detrimental to brain health, even when it does not meet clinical criteria for this pathology. .

From all these references, several foundational claims can be established: (a) that cardiovascular and metabolic health explains significant individual variation in the trajectory of cognitive aging, (b) that age-related neurocognitive decline is neither autonomous nor independent. of the health and function of peripheral organ systems, and (c) that experimental manipulations designed to improve physical health (e.g., blood pressure) are critical to determining causal links between cardiovascular and metabolic health and the age-related cognitive decline.

| 3. Early life adversity and neurocognitive aging |

Adverse childhood experiences, such as abuse, neglect, and extreme poverty, exert profound negative effects on health and well-being that persist well into adulthood. People who have been exposed to childhood adversity are at significantly increased risk of developing numerous chronic health conditions, including cardiovascular disease, T2D, and obesity, and exhibit accelerated brain aging relative to adults without a history of childhood adversity.

Despite these severe and persistent effects of early life adversity, it is unclear whether interventions administered in adulthood are able to reverse these effects.

| 4. Genetic risks and age-related cognitive decline |

Individual differences in age-related cognitive performance may also be attributed to the possession of genetic variants that cause molecular cascades that affect neurocognitive processes; That is, genetic factors influence neurobiological processes (e.g., neurotransmitter expression, growth factors, synaptic plasticity) that support cognitive processes, thus neuronal resilience, plasticity, and neuropathology that explain individual differences.

What is important in the context of this review is that individual variability, both in the onset and rate of age-related cognitive decline, is partially explained and predicted by genetic variation. This is essential to consider environmental exposures and health conditions that also predispose someone to accelerated cognitive decline. These results lead to speculation that the presence of cardiovascular health conditions moderates genetic variation, such that the combination of genetic risk and poor cardiovascular health exacerbates the risks of intellectual decline.

| 5. Bases for physical activity |

Physical activity is a general term that refers to movement that increases energy expenditure regardless of its intention or intensity, while exercise is a structured form of physical activity with the aim of improving physical fitness. In this context, many observational studies measure physical activity while exercise interventions provide a structured regimen that is designed to improve physical fitness.

Physical activity and exercise are behaviors that can be measured by self-report or through devices that record position and acceleration. In contrast, cardiorespiratory fitness is not a behavior but a physiological construct that correlates with the degree of physical activity and exercise one engages in and therefore can be modified by engaging in moderate to vigorous intensity physical activity (MVPA). .

| 6. The role of physical activity in cognitive aging |

Prospective longitudinal evidence unequivocally indicates that more physical activity early in life is associated with better cognitive functioning later in life, including a lower risk of developing dementia.

It is unclear from observational studies whether initial declines in cognitive function and signs of neurodegeneration or neuropathology could be influencing mobility, balance, motivation, and goals to participate in physical activity.

Despite a set of controlled clinical trials with evaluable sample sizes and apparent strength in the positive effects of exercise on cognitive performance in late adulthood, there are meta-analyses that have failed to find favorable effects of exercise on cognition. What factors could explain this heterogeneity? One possibility is that meta-analyses often differ in their inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Unfortunately, there are still no clear public health guidelines for prescribing exercise and optimizing its potential cognitive-enhancing effects in older adults. This limitation could be one of the primary sources of heterogeneity between studies. Specifically, we have little clarity about the intensity of exercise, the volume of activity per week, the minimum duration of an intervention, the frequency of weekly activity, whether activities should occur in periods of at least 10 minutes, and the type or mode of exercise that maximizes the effects.

Exercise does not appear to influence all cognitive processes uniformly and is unlikely to change performance on all cognitive tests; That is, physical activity appears to influence executive functions more than other cognitive domains. As such, studies that rely on measures of global cognitive function may be using insensitive measures to detect subtle cognitive improvements, especially in cognitively normal individuals.

The age of the participants may also influence the response; A meta-analysis concluded that adults aged 55 to 75 years would produce the greatest exercise-induced cognitive benefit, compared to older participants.

In summary, the magnitude of exercise-induced cognitive benefits is likely influenced by sample size, focus of statistical analyses, and study quality; the type, duration and intensity of exercise; baseline sex, age, and other lifestyle factors (activity levels); early life exposures, cardiovascular and metabolic health conditions (e.g., hypertension, obesity); and genetics, among many other factors.

Further examination of how these moderating factors influence the exercise-cognition link is crucial, as the results can be used to inform the creation of an algorithm to predict cognitive response to exercise by generating optimized precision medicine approaches.

| 7. Physical activity and dementia |

Dementia is a group of symptoms characterized by significantly greater than expected deficits in several cognitive domains, typically including episodic memory, as well as impairments in the ability to perform activities of daily living . Alzheimer’s disease is the most common type of dementia.

Current pharmaceutical treatments for dementia provide temporary symptomatic relief; However, they do not alter the course of the disease and often have undesirable side effects. Therefore, behavioral and lifestyle interventions, such as physical activity, may be alternative therapeutic approaches.

There is substantial diversity in the etiology of various types of dementia, and therefore several underlying biological changes, which may be differentially influenced by exercise interventions. For example, the hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease is the buildup of amyloid beta and tau proteins, which can be reduced by physical activity. However, frontotemporal dementia is primarily characterized by degeneration in the frontal and temporal lobes, and there is little research on how physical activity may affect this etiology. Furthermore, studies often do not distinguish between disease stage, except for a general distinction between mild cognitive impairment or dementia.

Therefore, physical activity may be effective as a treatment for dementia; however, a focus on early phases of the disease course and a more individualized treatment approach may be required for optimal cognitive benefit.

In addition to being a possible therapeutic for cognitive decline in dementia, physical activity has been examined as a method to delay or prevent the onset of the disease. In fact, evidence from observational research indicates that physical activity can reduce the risk of cognitive decline and dementia over a period of 1 to 12 years. Furthermore, greater physical activity in midlife is associated with a reduced risk of dementia in later life, making midlife a prime target for the implementation of preventive strategies.

Taken together, exercise could be effective as a method to prevent conversion to dementia and as a treatment to improve cognitive function in people diagnosed with dementia. This approach, however, likely requires an individualized exercise prescription and may be most effective early in the disease course, before neurodegeneration and neuropathology are advanced and widespread.

| 8. How physical activity shapes the aging brain |

Engaging in physical activity may increase the expression of growth factors that promote dendritic branching, which in turn results in volumetric changes that may mediate improvements in sleep quality.

Physical activity influences hundreds or thousands of molecular pathways. As such, it triggers many cellular cascades that likely influence the brain independently, additively, or multiplicatively. This is known as a “hammer effect,” that is, engaging in physical activity is like a shock to the system, an imprecise but highly effective means of influencing almost every organ system in the body (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A conceptual diagram illustrating three levels of mechanisms by which exercise possibly influences cognitive outcomes. This list is far from exhaustive, but it shows that the effects of exercise likely occur through a large number of pathways. Abbreviation: PET, positron emission tomography.

| 8.1. Evidence in animals |

Some of the research on physical activity and brain outcomes can be traced back to animal (primarily rodent) models of environmental enrichment (EE). Initial studies on EE compared groups of young animals raised in standard cage conditions with those raised in cages enriched with a combination of cognitive, social, and physical stimulation.

Animals housed in the enriched cages had signs of better brain health that persisted as the animals aged, including increased total brain volume and weight, higher levels of neurotrophic factors, neurogenesis, and decreased cell apoptosis.

The observed benefits of EE on learning and memory stimulated interest in applying EE to aging and neurodegenerative disease models. The conclusion that emerged was that EE can remedy some of the negative effects of normal and pathological aging on the brain. Furthermore, this remediation may occur preferentially in aging-sensitive regions such as the hippocampus.

| 8.2. Evidence in human neuroimaging |

Animal research provides important information about the molecular and cellular pathways that contribute to cognitive improvements resulting from physical activity. However, it is impossible with current technology to determine whether these same molecular and cellular pathways are affected by physical activity in humans. Instead, in humans we rely on examining peripheral blood markers or neuroimaging biomarkers to give us insight into possible biological mechanisms of physical activity on cognition.

In normal aging, for example, hippocampal gray matter volume declines at a rate of 1% per year beginning in middle age, a faster rate than many other brain regions. Furthermore, hippocampal impairment precedes and leads to declines in episodic memory in adulthood and accelerated hippocampal atrophy predicts conversion to mild cognitive impairment and dementia. These findings suggest that the structural integrity of the hippocampus may be an important biomarker for the trajectory of cognitive aging, at least in the context of relational and episodic memory performance.

Similar to cognitive performance, this heterogeneity in regional brain volumes may also be partly explained by participation in physical activity and variation in cardiorespiratory fitness. Indeed, higher levels of cardiorespiratory fitness and greater amounts of physical activity are consistently associated with larger hippocampal volumes in cognitively normal older adults and aging populations at high risk of cognitive decline.

Measures of brain function are also affected by exercise participation. Most of the evidence can be separated into two categories: studies of resting-state connectivity and those of task-evoked activation.

Supporting this interpretation, resting-state connectivity patterns have been associated with poorer cognitive performance on age-sensitive measures, such as episodic memory, in older adults.

Studies of task-evoked activation in aging populations have often reported that older adults show greater activation in task-related brain regions compared to younger adults to maintain the same level of performance. Compared with resting-state connectivity, the effects of physical activity on task-evoked brain activation have been less frequently examined, particularly in the context of randomized exercise interventions in older adults.

Although physical training has led to better cognitive performance in all of the previously mentioned studies, the pattern of changes in brain activation that supports such improvements differs between studies. The effects of exercise on task-evoked activation are likely to vary depending on the cognitive task (and perhaps the degree of difficulty).

| 8.3. Cardiovascular and cardiometabolic health |

Most evidence suggests that physical activity has beneficial effects on a variety of proximal mediators and risk markers for cardiovascular disease. These include blood pressure, cardiac autonomic control, systemic inflammation, glucose regulation, adiposity, and lipid levels.

Just as physical activity promotes angiogenesis in the brain, physical activity stimulates the proliferation and growth of endothelial cells in the periphery, increasing the density and diameter of the vasculature.

In addition to blood pressure, it has been speculated that physical activity could benefit brain function through its effects on body composition. Cellular and metabolic changes can be initiated that promote improvements in brain health outcomes regardless of the degree of weight loss achieved.

Physical activity also improves glucose and insulin regulation, both in healthy individuals and in those diagnosed with T2D. A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials of aerobic exercise demonstrated that increased physical activity reduced circulating glucose levels and improved HbA1c.

Inflammatory pathways have also been implicated in neurocognitive aging, and these pathways are modulated by physical activity. Several cross-sectional studies have shown that exercise is associated with lower levels of pro-inflammatory molecules, even when other factors that promote inflammation, such as adiposity, are taken into account.

It is also important to keep in mind one of the principles of health neuroscience: that there are reciprocal relationships between the body and the brain. Therefore, conceptualizing the relationship between cardiovascular and metabolic health and brain health as unidirectional is likely naïve and unrealistic. Exercise is likely to have a direct and immediate impact on gene expression and brain processes that, in turn, influence peripheral physiological functions, including cardiovascular and metabolic risk markers.

| 9. Conclusions |

We can conclude that physical activity unequivocally affects brain health outcomes. We argue here that this definition influences perceptions of cognitive aging. Rather than conceptualizing cognitive aging as an immutable and progressive downward slope, evidence from physical activity studies indicates that the brain remains more malleable in old age than previously believed. In other words, the aging brain retains some of its natural capacity for plasticity, and physical activity can take advantage of this property of the brain.

Why isn’t exercise or physical activity more commonly adopted by scientists and health professionals? There are at least four main reasons why scientists and public health officials are reluctant to emphasize physical activity to focus on neurocognitive health.

First, physical activity is often described as a non-pharmacological intervention. This unfortunate terminology denies rather than defines and carries the connotation that the molecular and cellular mechanisms of the effects are enigmatic. As such, this terminology could diminish perspectives on the robustness and effectiveness of physical activity. We argue that physical activity (and various other health behaviors) should be considered a vehicle for modifying endogenous pharmacology in contrast to medications which are inherently an exogenous method. Therefore, altering the messages and terminology around physical activity could influence perceptions of exercise as medicine.

Second, professionals continue to fight a battle that depends on the perception that the best way to exercise the brain is through intellectual activities. In fact, there are common stereotypes that physical activity takes time away from participation in academic activities. Educational policies that attempt to eliminate physical education and recess activities from the school curriculum to dedicate more time to traditional academic activities perpetuate this stereotype despite evidence to the contrary: academic achievement scores are often higher in schools than They promote physical education classes.

Third, some arguments are dismissive of physical activity due to the claim that long-term adherence is poor. We argue that this argument combines two separate issues, one related to the effectiveness of physical activity in modifying brain health and the other related to promoting adherence and behavior change. Most interventions, including pharmaceutical treatments, are plagued by poor treatment adherence. Improving adherence is certainly a challenge to overcome, but poor adherence does not nullify the effectiveness of the treatment or the objective of the prescription.

Finally, a common reason is that the scientific literature on the effects of physical activity on brain health is too murky and there is not enough consensus on its potential positive effects.

In summary , what we have learned from the impact of physical activity on cognitive aging provides a hopeful perspective on the potential to maintain higher levels of cognitive function well into adulthood. Although cognitive decline may be a pervasive consequence and some may argue that it is inevitable, there is evidence that the rate and magnitude of decline can be manageable through healthy behaviors such as exercise.