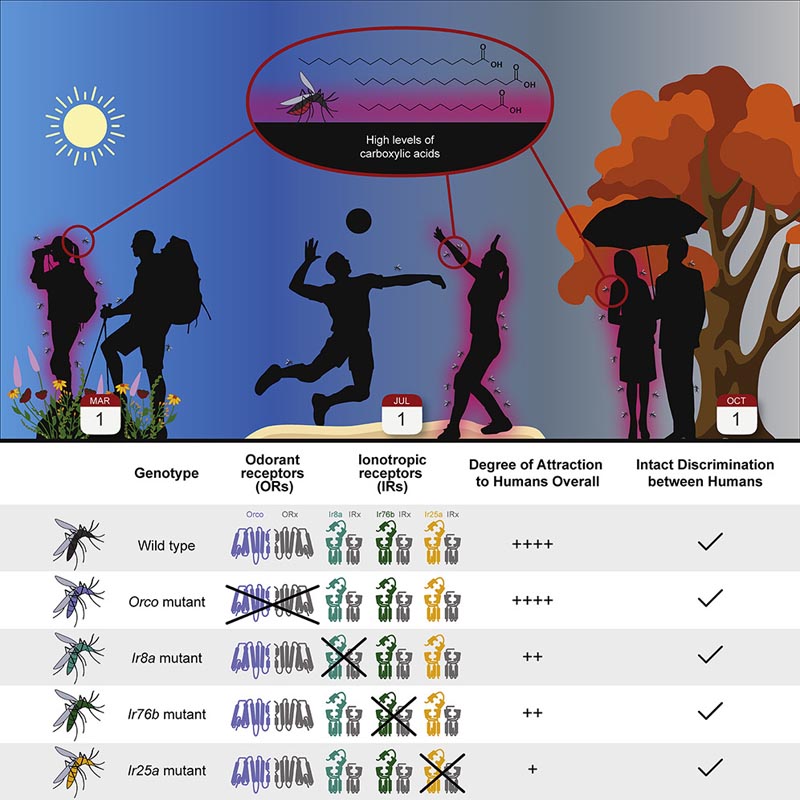

Highlights • Some people are consistently more attractive to mosquitoes than others, due to differences in skin odor. • IR mutants ( Ir25a and Ir76b ) show reduced overall attraction to humans. • Mosquitoes with extensive olfactory deficits can distinguish highly and weakly attractive people. • Very attractive people have higher levels of carboxylic acids in their skin. The differential attraction of mosquitoes to humans is associated with skin-derived carboxylic acid levels. |

Summary

Some people are more attracted to mosquitoes than others, but the mechanistic basis of this phenomenon is poorly understood. We test the attraction of mosquitoes to the odor of human skin and identify people who are exceptionally attractive or unattractive to mosquitoes. These differences remained stable for several years. Chemical analysis revealed that very attractive people produce significantly more carboxylic acids in their skin emanations. Mutant mosquitoes lacking chemosensory coreceptors were severely impaired in attraction to human odor, but retained the ability to differentiate highly attractive from unattractive people. The link between elevated carboxylic acids in the “mosquito magnet” human skin odor and phenotypes of genetic mutations in carboxylic acid receptors suggests that such compounds contribute to the differential attraction of mosquitoes. Understanding why some humans are more attractive than others provides information about which skin odors are most important to the mosquito and could inform the development of more effective repellents.

Comments

It is impossible to hide from a female mosquito : it will hunt any member of the human species by tracking our CO2 exhalations, body heat and body odor. But some of us are "mosquito magnets" who receive more than our fair share of bites. Blood type, blood sugar level, consumption of garlic or bananas, being a woman, and being a boy are popular theories as to why someone might be a preferred snack. However, for most of them, there is little credible data, says Leslie Vosshall, director of the Rockefeller Laboratory of Neurogenetics and Behavior.

This is why Vosshall and Maria Elena De Obaldia, a former postdoc in his lab, set out to explore the leading theory to explain the variable attractiveness of mosquitoes: individual odor variations connected to the skin microbiota. They recently demonstrated through a study that fatty acids emanating from the skin can create an intoxicating perfume that mosquitoes cannot resist. They published their results in Cell .

“There is a very, very strong association between having large amounts of these fatty acids on your skin and being a magnet for mosquitoes,” says Vosshall, Robin Chemers Neustein Professor at Rockefeller University and scientific director of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

A tournament that nobody wants to win

In the three-year study , eight participants were asked to wear nylon stockings over their forearms for six hours a day. They repeated this process over several days. Over the next few years, researchers tested the nylons against each other in every possible pairing through a round-robin style "tournament." They used a two-option olfactometer assay that De Obaldia built, which consisted of a plexiglass chamber divided into two tubes, each ending in a box containing a sock. They placed Aedes Aegypti mosquitoes, the main vector species for Zika, dengue, yellow fever and chikungunya, in the main chamber and watched as the insects flew through the tubes towards one nylon or another.

By far the most compelling target for Aedes aegypti was Subject 33, who was four times more attractive to the mosquitoes than the next most attractive participant in the study, and surprisingly 100 times more attractive than the least attractive, Subject 19.

The samples in the trials were not identified, so the experimenters did not know which participant had used which nylon. Still, they would notice that something unusual was afoot in any test involving Subject 33, because the insects would swarm toward that sample. “It would be obvious within seconds of starting the rehearsal,” says De Obaldia. “It’s the kind of thing that really excites me as a scientist. This is a real thing. This is a great effect.”

The researchers classified participants into high and low attractors and then asked what differentiated them. They used chemical analysis techniques to identify 50 molecular compounds that were elevated in the sebum (a moisturizing barrier in the skin) of high-attractive participants. From there, they discovered that the mosquito magnets produced carboxylic acids at much higher levels than the less attractive volunteers. These substances are found in sebum and are used by the bacteria on our skin to produce our unique human body odor.

To confirm their findings, Vosshall’s team enrolled another 56 people for a validation study. Once again, Subject 33 was the most attractive, and remained so over time.

“Some subjects were in the study for several years and we saw that if they were a mosquito magnet, they were still a mosquito magnet,” says De Obaldia. "Many things could have changed about the subject or his behavior during that time, but this was a very stable property of the person."

Even mutants find us

Humans primarily produce two kinds of odors that mosquitoes detect with two different sets of odor receptors: Orco and IR receptors. To see if they could engineer mosquitoes incapable of detecting humans, the researchers created mutants that were missing one or both receptors. The mutants remained attracted to humans and were able to distinguish between mosquito magnets and low attractors, while the IR mutants lost their attraction to humans to a variable degree but still retained the ability to find us.

These were not the results that scientists expected. "The goal was a mosquito that lost all attraction to people, or a mosquito that had a weakened attraction to everyone and couldn’t discriminate Subject 19 from Subject 33. That would be tremendous," Vosshall says, because it could lead to the development of repellents. of more effective mosquitoes. “And yet, that’s not what we saw. “It was frustrating.”

These results complement one of Vosshall’s recent studies, also published in Cell, which revealed the redundancy of the exquisitely complex olfactory system of Aedes aegypti. It is a safety mechanism that the female mosquito relies on to live and reproduce. Without blood, she can’t do it either. That’s why "she has a backup plan and is attuned to these differences in the skin chemistry of the people she goes after," Vosshall says.

The apparent unbreakability of the mosquito scent tracker makes it difficult to imagine a future in which we are not the number one food on the menu. But one potential avenue is to manipulate our skin’s microbiomes . It is possible that smearing the skin of a high-attractive person like Subject 33 with sebum and bacteria from the skin of a low-attractive person like Subject 19 could provide a mosquito-masking effect.

“We haven’t done that experiment,” Vosshall notes. “That’s a difficult experiment. But if that worked, then you could imagine that by having a dietary or microbiome intervention where you put bacteria on the skin that can somehow change the way they interact with sebum, then you could turn someone like Subject 33 into a Subject 19. But all that is very speculative.”

She and her colleagues hope this paper will inspire researchers to try other mosquito species, including the Anopheles genus, which spreads malaria, Vosshall adds: "I think it would be really cool to find out if this is a universal effect."