| 1. Background |

The pathological behavior of skin picking was first described in the 19th century by Erasmus Wilson.1 However, skin picking disorder (SPD) did not make its first appearance in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Disorders. (DSM) until its 5th edition in 2013.2 The DSM-5 defines PPD as “recurrent scratching of the skin that causes skin lesions,” which “is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance or other medical condition” and “not It is explained as a symptom of another mental disorder”; Other diagnostic criteria include “repeated attempts to decrease or stop skin picking” and “clinically significant discomfort or functional impairment.”2”

For the purposes of this discussion, PTE will be considered synonymous with neurotic excoriation, excoriation disorder, acne excoriée, and dermatillomania.3

The DSM-5 classifies PTSD as an obsessive-compulsive disorder and related disorder, distinguishing it from other diagnoses and practices that may involve skin picking but are not manifestations of obsessive-compulsive processes. For example, patients with Prader-Willi Syndrome, a syndromic form of obesity caused by the lack of expression of paternally active genes on the long arm of chromosome 15, are prone to skin picking.4

Additionally, certain cultural practices involving children produce skin lesions that can mimic the presentation of PE (e.g., cao gio , the Vietnamese practice of rubbing coins). These rituals do not inflict pain or permanent tissue injury and are not considered child abuse, so it is imperative that these cultural practices be recognized.5,6

| 2 . Epidemiology |

PTSD is a relatively common disorder.

The overall prevalence of PE has been reported to range between 1.4% and 5.4%,7,8 with a recent study of 10,169 American adults revealing a lifetime prevalence for PE of 3.1%.9 Patients with PTSD are significantly more likely to be women, and PTSD is frequently comorbid with other mental health problems, most commonly generalized anxiety disorder, depression, and panic disorder.9,10

Other common comorbidities include alcohol dependence, nicotine dependence, suicidal ideation, trichotillomania (TTM), compulsive nail biting, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.11,12 However, these epidemiological studies were conducted only in adults, emphasizing the need for similar studies focused on pediatric populations. Furthermore, PTSD was found to be the most common psychocutaneous disorder among adults and children.13

The mean age of onset of PE varies substantially1; However, the disorder has been found to be more common in childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood, indicating a significant role for the pediatric dermatologist in the identification and treatment of the disorder and the need for further research in this population. 14-16 While it may be the case that children of different ages present differently, this has not yet been documented in the PTSD literature.

| 3 . Diagnosis |

Although PTSD is considered a primary psychiatric disorder, it (along with other body-focused repetitive behaviors) is commonly diagnosed by dermatologists.16 Establishing a supportive, nonjudgmental relationship between the dermatologist, patient, and parent is essential to so that an honest discussion can occur regarding the origin of the patient’s skin lesions.

The diagnosis is made based on a clinical evaluation and the DSM-5 criteria; The authors also developed a brief PTSD assessment tool (modeled after the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale for Children), a clinician-administered tool, and a clinician-rated semi-structured interview, to assess PTSD severity. In children.

All patients with suspected PE should undergo a complete dermatological evaluation.

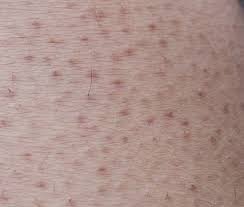

The most common sites for skin scratching include the face and upper extremities; Patients may begin by scratching an existing skin lesion, such as a scar, keratosis pilaris, or acne (as in acne excoriée), or they may begin by scratching normal skin.17 If the patient picks predominantly with the nails, the lesions are concentrated in areas of the body reachable with the dominant hand. This can result in the "butterfly sign" on patients’ backs, a pattern of excoriation that spares areas of the back that are difficult to reach with the hand.16

Patients should be evaluated for the severity of the excoriation and the presence of complications, such as scarring or infection, or coexisting dermatologic conditions. Disease severity assessment tools have been developed for adults; However, no instrument of this type has been validated in a pediatric population.18

Additionally, dermatologists should take a biopsychosocial approach when evaluating pediatric patients with suspected PE: dermatologists should ask questions to assess psychological aspects and social factors that contribute to the disease process, in addition to biological factors.19 Here, again, a strong dermatologist-patient and parent relationship is essential; The dermatologist must evaluate psychiatric and psychosocial comorbidity in the patient, which can guide specific treatments. For example, administering the PHQ-2 can help identify comorbid depression.20 This is particularly important because parents may resist accepting the diagnosis and the need for psychiatric evaluation.21

During the initial discussion of the diagnosis with parents, dermatologists should explain that the child may not be aware of his or her behavior; The information should be shared as positive news, as treatment can only begin after a diagnosis is made. Appropriate psychiatric referrals should then occur.22

| 4. Psychosocial impact |

Patients with PTSD carry a significant psychosocial burden ,23 and PTSD has an independent and negative impact on measures of quality of life in adults.12 Presumably, however, as is the case in other primary psychiatric disorders,24 PTSD is manifests differently in terms of psychosocial impact in pediatric patients compared to adults.

Although no studies have been conducted on the psychosocial impact of PTSD in pediatric patients, children and adolescents with visible skin conditions are especially prone to bullying,25 and childhood bullying is associated with negative emotional sequelae, including depression and anxiety, since the face is the most common site of skin excoriation, children with PTSD are likely to experience stigmatization.

| 5 . Driving |

Both pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment options in the treatment of PE were explored; However, there are no controlled trials on the treatment of PTSD in children. This presents both a challenge for the treatment of PTSD and an avenue for future research. Still, any intervention, including inactive comparison intervention such as placebo treatment, has a positive effect on adult PTSD, and this finding is presumably generalizable to children.26,27

The course of psychocutaneous disease , in general, is chronic and frequently relapsing, although children tend to have better prognoses than adults.19 Outcomes may be better in children with excoriée acne and other skin-picking behaviors that are secondary to an underlying or concomitant skin disease, as eradication of the primary lesion may resolve the skin picking trigger.

The mainstay of behavioral treatment for PTSD is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), a problem-oriented technique where thinking exercises are used to relieve symptoms, in this case skin picking.1,28

CBT, practiced by psychiatrists and mental health specialists, has been shown to be effective in reducing skin picking symptoms.29–31 And although the effectiveness of CBT in treating PTSD has not been studied in the pediatric population , CBT has been shown to be effective in the treatment of pediatric TMD in children as young as 7 years old32,33; Considering the similarities between TMD and PTSD (both are body-focused repetitive behaviors classified as obsessive-compulsive and related disorders in the DSM-5, and both are believed to arise from neurophysiological dysfunction in reward processing),34 this finding could be generalized to PET.

A specific subtype of CBT that has been shown to be particularly effective in treating PTSD is habit reversal therapy (HRT), a form of treatment that empowers patients to become aware of harmful habits such as skin picking so they can develop a competitive response. 35-37 While HRT has not been studied for PE in children, its efficacy has been demonstrated for pediatric trichotillomania.38

Although CBT and HRT are performed by psychiatrists or other mental health professionals, dermatologists should take advantage of available resources to become familiar with these techniques.22,39 Have a dermatologist who can provide accurate and detailed information about CBT and HRT will strengthen the dermatologist-patient-parent relationship. Furthermore, while there is a paucity of data on psychiatric referrals in children, only a minority of adult dermatology patients with PTSD are referred to psychiatry.10 This underlines the importance of dermatologists being aware of CBT and HRT so that can make referrals when appropriate.10

Several alternative behavioral therapies for PTSD have been explored. Yoga, aerobic exercise, acupuncture, biofeedback, electrical devices, and hypnosis have shown promise in treating repetitive body-focused behaviors such as PTSD, but require further study, preferably through controlled trials. 22,40–42 Hypnosis in particular has demonstrated efficacy in several cases of pediatric trichotillomania.40,41 Additionally, mindfulness techniques have been shown to increase HRT in the treatment of body-focused repetitive behavior disorders. 39

In addition to psychological therapy, physical barriers have been explored as an alternative treatment strategy for PE.43 For example, dermatologists can use bandages such as Unna boots to promote healing of skin lesions and prevent further skin excoriation. .44 Contingently applied protective equipment has been shown to reduce self-injurious behavior in patients with developmental disabilities, including children.45,46

In cases of excoriated acne, water-soluble herbal patches or hydrocolloid patches may be effective in treating the primary lesion while acting as a barrier to prevent further excoriation.47 Additionally, several skin replacement products have been developed that could be used to treat the PET; One modality involves the use of nanotechnology to provide antimicrobial properties and greater resistance to wear and tear compared to traditional materials. These products must be designed to be aesthetically pleasing to the pediatric patient, be personalized for them, and adapt to the patient’s skin tone, allowing for optimal psychosocial functioning during treatment.43

If behavioral therapy is insufficient to relieve symptoms or the patient refuses to seek mental health counseling (most referrals from dermatology to psychiatry are not made by patients),10 pediatric patients with PTSD may be treated with therapy. pharmacological.48 Various pharmacological treatments for PE have been studied, but there is no single gold standard. Additionally, there have been no controlled trials evaluating its use in the pediatric population.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors ( SSRIs) have been the most studied drug class in the treatment of PTSD. These inhibit the reuptake of serotonin in presynaptic cells, which increases the time that serotonin can be effective at the synapse; They are used as first-line antidepressants.49

Several SSRIs, including fluoxetine, citalopram, fluvoxamine, sertraline, and escitalopram, have demonstrated efficacy in relieving skin picking symptoms in adults.1,26,50 SSRIs may also have the added benefit of treating comorbid depression or anxiety. However, there have been no controlled trials studying SSRIs for PE in pediatric populations.

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) has also shown promise in the treatment of related obsessive-compulsive disorders, including PTSD, most likely by modulating glutamatergic and neuroinflammatory systems.50,51

A double-blind randomized trial found that NAC significantly improved PE symptoms in adult patients with a target dose of 3000 mg/day; however, there were no differences in psychosocial functioning between the groups.52 Additionally, an open-label pilot study found that 450–1200 mg/day of NAC improved skin-picking behaviors in all 35 patients in an ODS treatment study. Prader-Willi, a group that included children.53

And in one case report, a 12-year-old patient with TMD showed significant improvement after initiation of 1200 mg/day of NAC.54 However, although trials of NAC have demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of TMD in adults, A 1:1 randomized controlled trial of 39 pediatric TMD patients treated with 1200 mg/day NAC versus placebo for 16 weeks failed to demonstrate efficacy.55 Additional studies are needed to elucidate the impact of NAC in children with TPE.

Other medications have been studied in adults with PE. Lamotrigine, an anticonvulsant, showed effectiveness in an open-label trial with 16 participants receiving 12.5–300 mg/day,56 while another trial with 7 participants receiving the same dose range failed to find a significant improvement over placebo. .57 Additionally, a study of 3 adult patients treated with inositol showed a reduction in skin picking.58 These treatments have not yet been tested in children.

Case reports have suggested potential therapeutic avenues for future research in pediatric PE. Atomoxetine (25 mg/day), a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, and methylphenidate (10 mg/day), a stimulant, have demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of PTSD comorbid with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in a 9-year-old patient. and 10 years, respectively.59,60 Additionally, an 11-year-old boy with an intellectual disability who exhibited repetitive skin-picking behaviors was successfully treated with 1.5 mg/day of risperidone, an antipsychotic.61 These therapies should be studied on a larger scale.

| 6 . Conclusion |

PTSD is a common and still understudied disorder, especially in pediatric patients.

Dermatologists who suspect their patient has PTSD should focus on developing an honest and trusting relationship with the patient and parents so that they can be referred to an appropriate psychiatrist to institute and begin treatment. Unfortunately, treatment options for PE remain limited, and their effectiveness remains unconfirmed in the pediatric population.

Future areas of study should focus on identifying new treatments for PTSD, as well as evaluating the role of current psychological and pharmacological therapies in children with the disorder; Additionally, skin barrier and replacement technology may be an alternative strategy to prevent complications, promote wound healing, and discourage skin picking behavior.

| Comment |

Skin excoriation disorder in pediatrics is an underdiagnosed process that requires a high index of suspicion since its signs and symptoms overlap with those of other common processes in childhood.

It is essential to perform a thorough physical examination, evaluate signs of psychological and psychiatric disorders, and establish a relationship of trust with the patient and family to make appropriate referrals.

Joint monitoring by the pediatrician, dermatologist and mental health specialist is essential to achieve a complete approach and establish a consensual treatment with continuous re-evaluations according to the evolution of each individual patient.