A new scientific statement from the American Heart Association says current cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk assessments are insufficient for women of non-white races and ethnicities

Highlights of the statement:

|

Summary

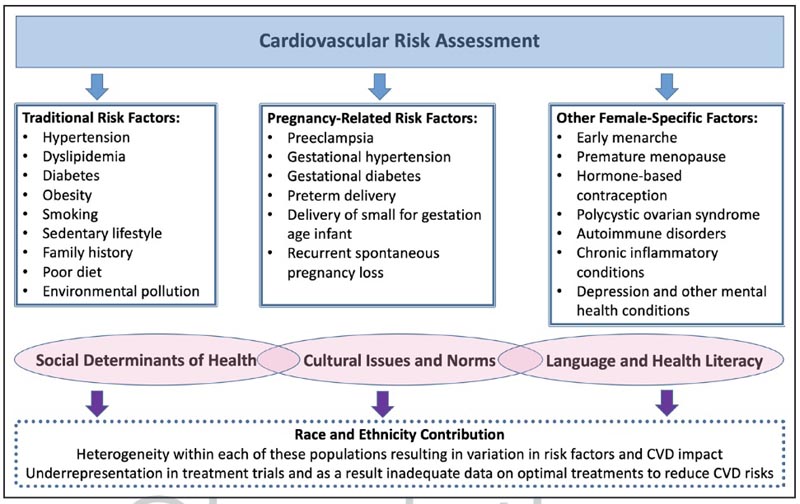

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in women, but there are differences between certain racial and ethnic groups. Aside from traditional risk factors, behavioral and environmental factors and social determinants of health affect cardiovascular health and risk in women. Language barriers, discrimination, acculturation, and access to health care disproportionately affect women of underrepresented races and ethnicities. These factors result in a higher prevalence of cardiovascular diseases and significant challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of cardiovascular conditions. Culturally sensitive, peer-led health professional and community education is a necessary step in cardiovascular disease prevention. Equitable access to evidence-based cardiovascular preventive health care must be available to all women, regardless of race and ethnicity; however, these guidelines are not equally incorporated into clinical practice. This scientific statement reviews current evidence on racial and ethnic differences in cardiovascular risk factors and current cardiovascular preventive therapies for women in the United States.

It is important to include nonbiological factors and social determinants of health in cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk assessment for women, particularly those of various non-white races and ethnicities, according to a new scientific statement from the American Heart Association published in Circulation , the Association’s flagship peer-reviewed professional journal.

Comments

“Risk assessment is the first step in preventing cardiovascular disease, but there are many limitations to traditional risk factors and their ability to comprehensively estimate risk in women,” said Jennifer H. Mieres, MD, FAHA, Vice President of the Scientific Statements Writing Committee and Professor of Cardiology at the Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra Northwell in Hempstead, NY Notably, large patient data registries used to develop cardiovascular risk assessment formulas or algorithms lack racial and ethnic diversity , so they may not accurately reflect the risk for women from underrepresented groups.

A 2022 American Heart Association presidential notice called understanding the impact of race and ethnicity on cardiovascular risk factors in women critical to incorporating those specific risks into prevention plans and reducing the high burden of cardiovascular disease among women of diverse origins. This new scientific statement responds to the presidential advisory as a review of current evidence on racial and ethnic differences in cardiovascular risk factors for women in the US.

What traditional risk formulas omit about women in general

Traditional formulas for determining cardiovascular disease risk include type 2 diabetes, blood pressure, cholesterol, family history, smoking, physical activity level, diet, and weight. These formulas do not take into account sex-specific biological influences on cardiovascular risk or medications and conditions that are more common among women than men.

Female-specific factors that should be included in the cardiovascular risk assessment are the following:

|

“Equitable cardiovascular health care delivery for women depends on improving the knowledge and awareness of all members of the health care team about the full spectrum of cardiovascular risk factors, including predominant and female-specific risk factors.” ”said Mieres, who is also Director of Diversity and Inclusion at Northwell Health.

Non-traditional and sex-specific risk factors

There has been much debate about the usefulness of incorporating non-traditional risk factors into standard risk assessment tools. The US Preventive Services Task Force concluded in 2018 that there was not enough evidence to say whether to add non-traditional risk factors such as high-sensitivity C-reactive protein or coronary artery calcium scoring to the tools. traditional risk assessment, would benefit patients who do not have CVD symptoms.

However, there is much to consider when examining sex-specific factors and their impact on CVD risk. For example, pregnancy -related risk factors , such as preeclampsia and eclampsia , demonstrate notable racial and ethnic disparities, with the highest age-adjusted prevalence observed in non-Hispanic black women compared to Hispanic/Latina and non-Hispanic white women. . This puts the mother at risk of severe morbidity and increases future cardiovascular risk. Asian women may have the highest risk of developing cardiovascular complications from preeclampsia. In the United States, 2 out of 3 women who experience preeclampsia die from heart disease. Furthermore, the impact of pregnancy-related risk factors extends to the children of women with preeclampsia and increases their likelihood of having hypertension and obesity, placing them at higher risk for CVD, particularly heart disease and CVA. In particular, nearly one-third of young adults with hypertension were born to mothers who experienced hypertension during pregnancy.

Menstrual cycle history , including age at onset of menarche and menopause, is another non-traditional assessment of sex-specific risk factors that should be considered when evaluating women for CVD risk. Early menarche is associated with adiposity and metabolic syndrome, which is suggested to be attributable, in part, to increased lifetime exposure to estrogens. Additionally, early menarche has been associated with an increased risk of CVD events and death from all causes. Both early and late age at menarche have been associated with an increased risk of CHD, with the suggestion that inflammatory biomarkers mediate the development of angiographic CHD and may play a role in mediating destabilization of atherosclerotic plaque.

Regarding menopause , it is imperative to state that menopause is a natural part of a woman’s life cycle, and the changes that occur during this phase of life can affect heart health. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome increases with menopause. Furthermore, decreased estrogen levels lead to changes in the lipid profile by reducing protective high-density lipoprotein and elevating apolipoprotein B and triglyceride levels, thereby increasing the risk of CVD. Estrogen levels have also been associated with increased intra-arterial cholesterol deposition and increased visceral fat, which are associated with increased triglycerides and insulin resistance. of reproductive age that also has harmful effects on the cardiovascular risk profile.

Due to the many clinical disorders associated with PCOS , such as hypertension, altered lipid and glucose metabolism, vascular injury, and systemic inflammation, PCOS has previously been recommended to be considered a cardiovascular risk factor.

Those with autoimmune disorders, of whom approximately 80% are women, are at increased risk of developing CVD and premature CVD.

Autoimmune diseases show a clear sexual bias with a greater prevalence among women, occurring in a ratio of 2:1, with some disorders being genetic and others sporadic. Regardless of the mechanism of manifestation, patients with autoimmune disease are predisposed to accelerated atherosclerosis, increased risk of CVD, and worse outcome of cardiovascular events as a result of inflammation-mediated endothelial dysfunction and accelerated atherosclerosis.

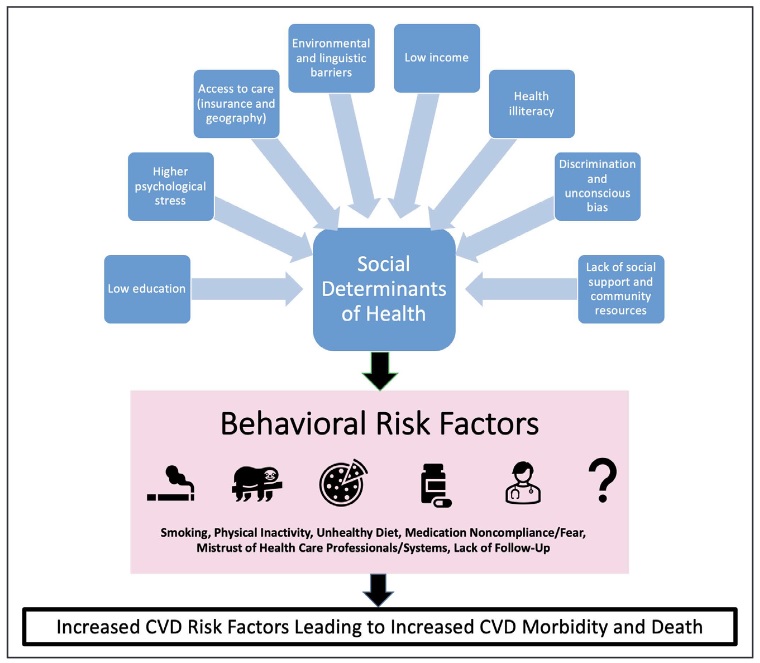

Importance of social determinants of health in risk assessment

Social determinants of health play an important role in the development of CVD among women, with disproportionate effects on women of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. These determinants include economic stability, neighborhood safety, working conditions, environmental hazards (such as exposure to air pollution), education level, and access to quality health care. The impact of social factors is recognized in the way they affect behavioral risk factors, such as smoking, physical activity, diet, and appropriate use of medications.

“It is critical that risk assessment be expanded to include social determinants of health as risk factors if we are to improve health outcomes for all women,” said Laxmi S. Mehta, MD, FAHA, Chair of the Writing Group and Director of Preventive Cardiology and Women’s Cardiovascular Health at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, Ohio. “On the other hand, it is important for the health care team to consider social determinants of health when working with women on shared decisions about the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases.”

Differences in women’s cardiovascular disease risk by race and ethnicity

While cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in women, the statement highlights significant racial and ethnic differences in cardiovascular risk profiles:

Non-Hispanic black women ( an umbrella term that encompasses African Americans, Africans, and Caribbeans) in the US have the highest prevalence of high blood pressure in the world, over 50%. They are also more likely to develop type 2 diabetes; having obesity or extreme obesity; and losing their lives due to smoking-related diseases. Non-Hispanic black women are disproportionately affected by traditional risk factors and experience the onset of CVD at younger ages. Social determinants of health are a key driver of this disparity, as detailed in the AHA’s 2022 Cardiovascular Disease Statistics Update.

Hispanic/Latina women ( referring to women of any racial and ethnic background whose ancestry is from Mexico, Central America, South America, the Caribbean, or other Spanish-speaking countries) have a higher rate of obesity compared to men Hispanics/Latinos. Hispanic/Latina women born in the U.S. also have higher rates of smoking than those who were born in another country and immigrated to the U.S. Paradoxically, despite higher rates of type 2 diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome, CVD mortality rates are 15% to 20% lower in Hispanic/Latina women than in non-Hispanic white women. This “Hispanic paradox” may be due to the lumping together of diverse Hispanic subcultures in research data, which does not take into account different levels of risk among individual subgroups of Hispanic/Latino people or the possibility of immigrant bias. healthy.

American Indian and Alaska Native women ( a diverse population that includes hundreds of federally recognized and unrecognized tribes in the U.S.) account for a higher rate of tobacco use than other groups, with 1 in 3 women who currently smokes. Type 2 diabetes is the leading risk factor for heart disease among Native American women; however, rates vary by region, with prevalence as high as 72% among women in this group in Arizona, and just over 40% among those in Oklahoma, North Dakota, and South Dakota. Unfortunately, understanding the cardiovascular health of American Indians/Alaska Natives is challenging due to small sample sizes in national data, racial/ethnic misclassification, or other factors.

Asian American women ( with origins in the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent) have varying rates of CVD risk within Asian subgroups: rates of high blood pressure are 30% among Chinese women and 53% % among Filipinos; rates of low HDL (good) cholesterol and high triglycerides are higher among indigenous Asian and Filipino women; and the prevalence of type 2 diabetes is highest among women in Southeast Asia. The BMI level for increased risk of type 2 diabetes is lower for Asians than for other racial groups. Asian Americans are less likely to be overweight or obese compared to other racial groups; However, at the same BMI, they have higher rates of high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes. Higher levels of body fat and body fat distribution may explain these differences: Recent research reveals that Asian people They generally have a higher percentage of body fat than non-Hispanic white people of the same age, sex, and body mass index. Additionally, studies have shown that Chinese, Filipino, and indigenous Asian people have more abdominal fat compared to non-Hispanic whites and blacks.

“When personalizing CVD prevention and treatment strategies to improve women’s cardiovascular health, a one-size-fits-all approach is unlikely to be successful for everyone ,” Mieres stated. “We must be aware of the complex interaction of sex, race and ethnicity, as well as social determinants of health, and how they affect cardiovascular disease risk and adverse outcomes to avoid future CVD morbidity and mortality.” ”.

Future cardiovascular disease prevention guidelines can be strengthened by establishing culturally specific lifestyle recommendations, tailored to cultural norms and expectations that influence behaviors, beliefs, and attitudes about diet, physical activity, and healthy weight. according to the statement. The Writing Committee calls for community initiatives, faith-based community partnerships, and peer support to encourage a healthy lifestyle to improve primary prevention of cardiovascular disease among women from underrepresented groups. The statement also recommends further research to address gaps in our knowledge about risk factors among women, including collecting data specific to subgroups of each race and ethnicity.

Conclusions

Assessment of CVD risk in women is multifaceted, moving beyond traditional risk factors to include sex-specific biological risk factors and incorporating race and ethnicity and nonbiological factors: SDOH and environmental and behavioral factors. Greater focus on addressing adverse levels of all CVD risk factors among women of underrepresented races and ethnicities is warranted to prevent future CVD morbidities and deaths.

Adverse social factors, such as access to health care, immigration status, language barriers, discrimination, acculturation, and environmental racism (the disproportionate impact of environmental hazards on people of color) are common in communities of underrepresented races and ethnicities and pose a significant problem and challenge in the diagnosis of CVD and the application of treatment modalities.

Culturally sensitive, peer-led health professional and community education is a necessary step in CVD prevention. Equitable access to evidence-based, guideline-approved cardiovascular preventive healthcare should be available to all women, regardless of race and ethnicity. Despite this knowledge, these guidelines are not equally incorporated into practice, highlighting a call to action.

Download the complete document in English here .

This scientific statement was prepared by the volunteer writing group on behalf of the Committee on Cardiovascular Diseases and Stroke in Women and Underrepresented Populations of the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart Association; the Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing Council; the Hypertension Council; the Council on Permanent Congenital Heart Disease and Heart Health in Young People; the Cardiometabolic Health and Lifestyle Council; the Peripheral Vascular Disease Council; and the Stroke Council. The American Heart Association ’s scientific statements promote greater awareness of cardiovascular disease and stroke and help facilitate making informed health care decisions. Scientific statements describe what is currently known about a topic and what areas need more research. While scientific statements inform guideline development, they do not make treatment recommendations. The American Heart Association guidelines provide the Association’s official clinical practice recommendations.

Other co-authors are Gladys P. Gladys P. Velarde, MD, FAHA; Jennifer Lewey, MD, MPH; Garima Sharma, MD; Rachel M. Bond, MD; Ana Navas-Acien, M.D., Ph.D.; Amanda M. Fretts, M.P.H., Ph.D.; Gayenell S. Magwood, Ph.D., RN, FAHA; Eugene Yang, MD; Roger S. Blumenthal, MD, FAHA and Rachel-Maria Brown, MD Public data for the authors is found in the article.