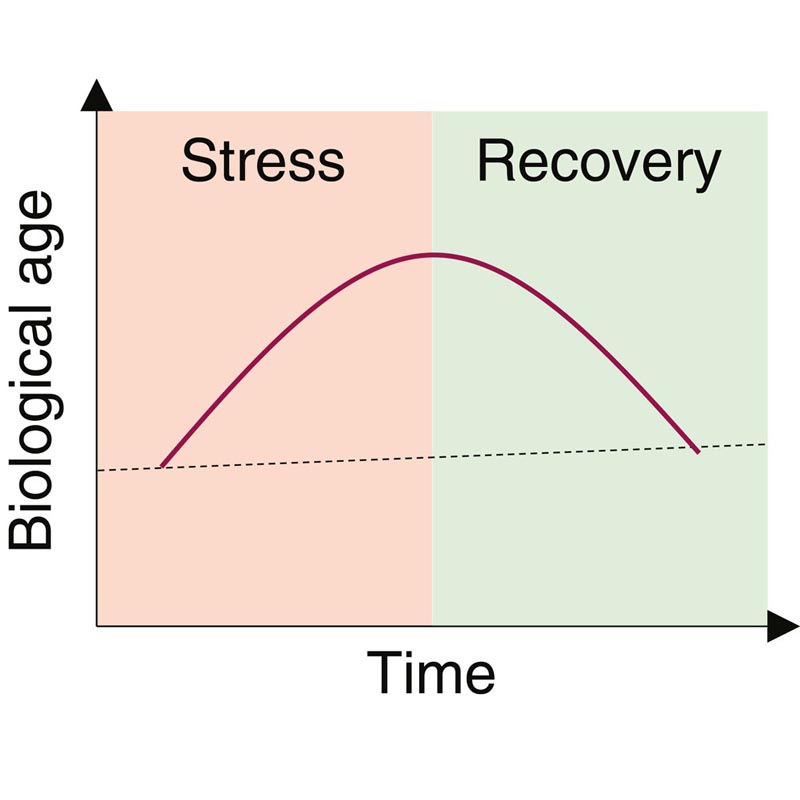

The biological age of humans and mice undergoes a rapid increase in response to various forms of stress, which reverses after recovery from stress, according to a new study. These changes occur over relatively short time periods of days or months, consistent with multiple independent epigenetic aging clocks.

Summary Aging is classically conceptualized as an increasing trajectory of accumulation of damage and loss of function, leading to increased morbidity and mortality . However, recent in vitro studies have raised the possibility of age reversal . Here we report that biological age is fluid and exhibits rapid changes in both directions. At the epigenetic, transcriptomic, and metabolomic levels, we found that the biological age of young mice is increased by heterochronic parabiosis and restored after surgical detachment. We also identified transient changes in biological age during major surgery, pregnancy, and severe COVID-19 in humans and/or mice . Together, these data show that biological age undergoes a rapid increase in response to various forms of stress, which is reversed after recovery from stress. Our study uncovers a new layer of aging dynamics that should be taken into account in future studies. Elevation of biological age by stress may be a quantifiable and actionable target for future interventions. |

Comments

The biological age of humans and mice undergoes a rapid increase in response to various forms of stress, which is reversed after recovery from stress, according to a study published in the journal Cell Metabolism . These changes occur over relatively short time periods of days or months, consistent with multiple independent epigenetic aging clocks.

"This finding of fluid, fluctuating, and malleable age challenges the long-standing conception of a unidirectional upward trajectory of biological age over the life course," says study co-senior author James White of the Faculty of Duke University Medicine. "Previous reports have hinted at the possibility of short-term fluctuations in biological age, but the question of whether such changes are reversible, until now, remained unexplored. Critically, the triggers for such changes were also unknown."

The biological age of organisms is thought to increase constantly throughout the life course, but it is now clear that biological age is not indelibly linked to chronological age. Individuals may be biologically older or younger than their chronological age implies. Furthermore, growing evidence in animal models and humans indicates that biological age can be influenced by diseases, drug treatments, lifestyle changes, and environmental exposures, among other factors.

"Despite widespread recognition that biological age is at least somewhat malleable, the extent to which biological age undergoes reversible changes throughout life and the events that trigger such changes are unknown," says study co-senior author Vadim Gladyshev of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School.

To address this knowledge gap, researchers harnessed the power of DNA methylation clocks, which were innovated based on the observation that methylation levels of various sites across the genome change in predictable ways over the course of time. chronological age. They measured changes in biological age in humans and mice in response to various stressful stimuli. In a series of experiments, researchers surgically joined pairs of mice that were 3 and 20 months old in a procedure known as heterochronic parabiosis .

The results revealed that biological age can increase for relatively short periods of time in response to stress, but this increase is transient and tends to return to baseline after recovery from stress. At epigenetic, transcriptomic, and metabolomic levels, the biological age of young mice was increased by heterochronic parabiosis and restored after surgical detachment.

"An increase in biological age following exposure to aged blood is consistent with previous reports of detrimental age-related changes in heterochronic blood exchange procedures," says first author Jesse Poganik of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School. "However, the reversibility of such changes, as we observed, has not yet been reported. From this initial information, we hypothesized that other natural situations could also trigger reversible changes in biological age ."

As predicted, transient changes in biological age also occurred during major surgery, pregnancy, and severe COVID-19 in humans or mice. For example, trauma patients experienced a sharp and rapid increase in biological age following emergency surgery. However, this increase was reversed and biological age was restored to baseline in the days following surgery. Similarly, pregnant women experienced postpartum biological age recovery at different speeds and magnitudes, and an immunosuppressive drug called tocilizumab enhanced the biological age recovery of convalescent COVID-19 patients.

"The findings imply that severe stress increases mortality, at least in part, by increasing biological age," says Gladyshev. "This notion immediately suggests that mortality may decrease by reducing biological age and that the ability to recover from stress may be an important determinant of successful aging and longevity. Finally, biological age may be a useful parameter for assessing stress." physiological and its relief."

Additional findings showed that second-generation human DNA methylation clocks provide consistent results, while first-generation clocks generally lack the sensitivity to detect transient changes in biological age. "Whatever the underlying reason, these data highlight the critical importance of judicious selection of DNA methylation clocks appropriate for the analysis at hand, especially in light of the many clocks that continually emerge," says Gladyshev.

While this study highlights a previously unlearned aspect of the nature of biological aging, the researchers recognize some important limitations. Although they characterized the parabiosis model at multiple omics levels, they primarily relied on DNA methylation clocks to infer biological age in human studies because these tools are the most powerful aging biomarkers currently available. Furthermore, the findings are limited in their ability to investigate connections between short-term fluctuations in biological age and trajectories of biological aging across the lifespan.

"Our study uncovers a new layer of aging dynamics that should be taken into account in future studies," says White. "A key area for further research is to understand how transient elevations in biological age or successful recovery from such increases may contribute to accelerated aging over the life course."