| Highlights: |

• Sepsis-associated encephalopathy (SEA) describes an acute cognitive dysfunction that occurs as a consequence of a systemic or peripheral infection outside the central nervous system. • EAS is an important cause of delirium. Acute cognitive dysfunction in the context of infection is associated with increased mortality and may be linked to an increased risk of subsequent dementia. • The pathophysiology is not well understood, but likely involves systemic inflammation in response to infection that drives microglial activation and blood-brain barrier dysfunction. • Therapy is based on timely control of the cause and antimicrobial treatment with good supportive care. Specific agents, such as the alpha-2 agonist dexmedetomidine, have shown promise in postoperative delirium and may be useful in EAS, but more trials are needed. |

| Introduction: definitions, pathophysiology and epidemiology |

Sepsis-associated encephalopathy (SEA) is a term that has been used to describe acute cognitive dysfunction in patients with systemic or peripheral infections in the absence of central nervous system (CNS) infection and other causes of encephalopathy.

EAS is a frequent complication of sepsis, affecting up to 70% of patients, and is one of the main causes of delirium; an acute disorder of consciousness that is frequently encountered but poorly understood.

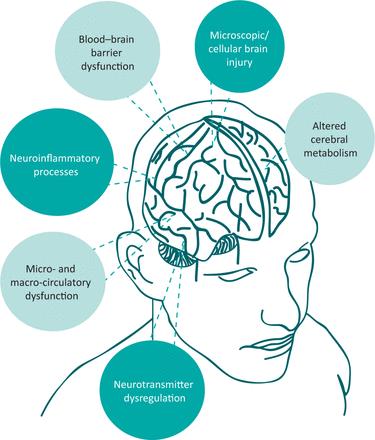

The etiology of EAS is likely multifactorial ( Figure 1 ). Another key consideration is the degree of pre-existing brain injury and the “cognitive reserve” that patients have, as this influences the magnitude of insults necessary to disrupt brain homeostasis such that overt cognitive dysfunction is evident.

Figure 1. Proposed mechanisms of sepsis-associated encephalopathy.

| Clinical evaluation and investigations |

EAS should be suspected in patients who present evidence of infection and an acute alteration in mental status. The spectrum of cognitive dysfunction seen in EAS can range from reduced concentration to mild confusion, with or without agitation, and auditory/visual hallucinations, to fluctuations in consciousness and even coma.

Currently there are no specific neuroradiological, physiological or biochemical investigations that can reliably diagnose EAS. In general, EAS remains a predominantly clinical diagnosis and relies on clinicians to perform thorough medical histories, physical examinations, and cognitive evaluations on all suspected patients. They should be aware that EAS is a much more common cause of acute confusion in a patient presenting with fever than primary CNS infections and, given the breadth of differential diagnoses available, a pragmatic approach should be taken.

| Key points in the history and physical examination |

The clinical history in case of suspected EAS should include an examination of current or recent symptoms of infection (both CNS and non-CNS), symptoms of organ dysfunction, susceptibility to EAS (e.g., previous pathology of the CNS or episodes of delirium), symptoms suggesting an alteration in mental status, mood disturbances, and substance abuse. A medication review should also be performed.

The physical examination should focus on determining a potential source of infection. Specific types of organ dysfunction may also have observable clinical signs (e.g., jaundice in liver failure) and may indicate alternative causes of encephalopathy. Neurological examination in EAS is usually normal and focal signs suggest an alternative etiology.

However, patients with EAS may present with signs of delirium including agitation, hallucinations, reduced concentration, and inattention throughout the clinical examination. Patients can also be expected to have a fluctuating or reduced level of consciousness. This can progress to coma, so doctors should be alert for any changes in mental status.

| Delirium evaluation |

While early detection of delirium is valuable for the ultimate diagnosis of EAS, it is important for clinicians to remember that delirium and EAS are not synonymous, as EAS is only one of many causes of delirium.

For acute medical evaluation, naming the months of the year backwards (MOTYB test) is probably the most reliable single-item bedside test.

| Key management aspects |

Prompt treatment of sepsis limits the possibility of developing adverse cognitive sequelae. Because EAS does not correlate with direct CNS infection, treatment should be directed toward the most likely source of peripheral or systemic infection. In the absence of an overt source of infection or an identified causative organism, broad-spectrum antibiotics should be administered after appropriate cultures have been taken.

Once an infectious syndrome or responsible organism has been identified, antibiotic therapy can be limited according to resistance patterns and local antibiotic guidelines. Care should also be taken to consider common viral causes of EAS (such as respiratory viruses), as there are potential therapeutic options available for influenza (e.g., antivirals) and COVID-19 (e.g., antivirals, immunomodulators, and others). agents).

Supportive treatment is also crucial to prevent further neurological damage, particularly by addressing abnormal physiology, comorbidities, nutrition, and electrolytes.

Despite numerous trials of pharmacological interventions, no effective treatment options have been identified for the treatment of EAS. Additionally, some commonly used drugs (such as psychotropics, benzodiazepines, and opioids) may be independent risk factors in the development/maintenance of delirium and should be discontinued whenever possible.

| Forecast |

The relationship between EAS and long-term cognitive decline is unclear. However, there is data to suggest that major infections (i.e., those resulting in hospitalization) are associated with subsequent significant cognitive impairment. Similarly, systemic inflammatory events, most of which were secondary to infections, have been reported to accelerate the onset of dementia and accelerate progression in those with an established diagnosis.

| Conclusion |

EAS is a heterogeneous condition due to variability in culprit pathogens, pathophysiology, and treatment. It remains an acute and frequent complication of sepsis with chronic sequelae in some, highlighting that the brain is an organ that can be profoundly affected during episodes of infection.