A team of neuroscientists from the University of Padua in Italy, in collaboration with a colleague from the CNRS and Paris Cité University, has found evidence suggesting that the neural development of babies still in the womb is affected by language. that they hear from their mothers.

Summary

Human babies acquire language with remarkable ease compared to adults, but the neural basis of their remarkable brain plasticity for language remains poorly understood. Applying a scaling analysis of neuronal oscillations to address this question, we show that newborn electrophysiological activity exhibits increased long-range temporal correlations after speech stimulation, particularly in speech heard before birth, which indicates the early emergence of brain specialization for native language.

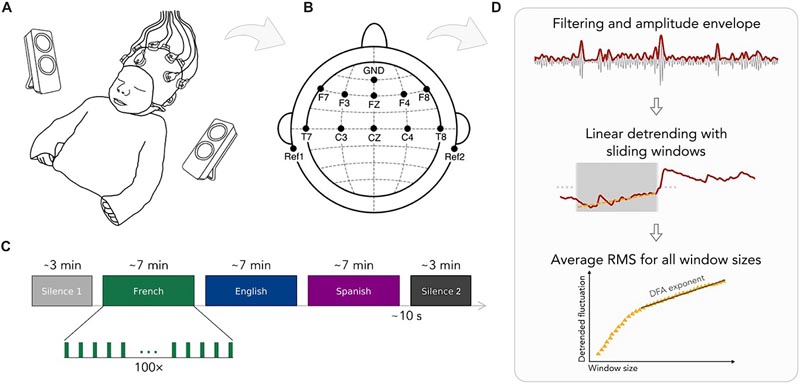

Figure . Illustration of the experimental paradigm and the analysis process. (A) The experimental setup used in the study. (B) EEG channel locations. (C) The experimental design. (D) The detrended fluctuation analysis (DFA).

Comments

In their paper published in the journal Science Advances , the group describes research they conducted with newborn babies fitted with EEG caps.

Previous research has shown that babies still in the womb (from about seven months old ) can hear when their mother speaks. They may also hear other sounds, such as other voices, music, and general noises. They can also recognize their mother’s voice after birth and specific melodies related to her speech. Less understood is what kind of impact hearing such things has on the neural development of the baby’s brain. To find out more, the research team in Italy carried out an experiment with 33 newborns and their mothers, all of them native French speakers.

The experiments consisted of placing all newborn volunteers in caps that allowed EEG monitoring in the days after birth. While the babies slept, the researchers played recordings of a person reading different language versions of the book "Goldilocks and the Three Bears . " The EEG recordings began during a period of silence before the book was played, continued during the reading, and also during another period of silence afterwards.

By studying the EEG readings, the research team found that babies who heard the story in French showed an increase in long-range temporal correlations, all of a type that had previously been associated with speech perception and processing. . The researchers suggest that this finding is evidence that the baby’s brain is affected in a unique way by exposure to a single language while still in the womb; in this case, French.

The researchers also performed a detrended fluctuation analysis on the EEG readings as a means of measuring the strength of the temporal correlations and found that they were strongest in the theta band, which previous research has shown to be associated with speech units. syllable level. This, the team suggests, shows that the babies’ brains became attuned to the linguistic elements present in the language they had heard.

The research team also found that the baby’s neural response was seen more strongly in the EEG readings when the book was read in French, suggesting that prenatal exposure to a particular language played a role in the neural development of his baby. brain .

Discussion and Conclusions

Together, these results provide the most compelling evidence to date that language experience already shapes the functional organization of the infant brain, even before birth. Exposure to speech causes rapid but long-lasting changes in neural dynamics and therefore increases infants’ sensitivity to previously heard stimuli. This facilitative effect is present specifically for language and the frequency band experienced prenatally.

These results converge with observations of greater power in the electrophysiological activation of the newborn brain after linguistic stimulation and suggest that the prenatal period lays the foundation for further language development , although it is important to note that its impact is not deterministic, since children, if exposed from a young age, remain capable of acquiring a language even in the absence of prenatal experience, for example, in the case of premature babies, immigrants or children adopted internationally or after cochlear implants.

It remains an open question whether the facilitative effect of prenatal experience is specific to the speech domain. Behaviorally, newborns have been shown to recognize music to which they have been exposed prenatally, thereby showing behavioral evidence of learning in auditory domains other than language. Future neuroimaging studies will be necessary to test whether this learning is similarly accompanied by changes in neural temporal dynamics of the type we observe here for language.

From a broader perspective, our findings document the power-law scaling of neural activity during language processing in the newborn brain. This statistical property is a hallmark of critical phenomena and it has been suggested that criticality in the brain is related to optimal states of information transmission and storage. Therefore, the newborn brain may already be in an optimal state for efficient speech and language processing, supporting the unexpected language learning abilities of human babies.