Human neuronal larva migrans caused by Ascarid Ophidascaris robertsi

Key takeaways

Summary We describe a case in Australia of human neural larva migrans caused by the roundworm Ophidascaris robertsi , of which Australian carpet pythons are definitive hosts. We made the diagnosis after a live nematode was removed from the brain of a 64-year-old woman who was immunocompromised by hypereosinophilic syndrome diagnosed 12 months earlier. |

Ophidascaris species are nematodes that exhibit an indirect life cycle; Several genera of Old and New World snakes are definitive hosts. O. robertsi nematodes are native to Australia, where the definitive hosts are carpet pythons (Morelia spilota). Adult nematodes live in the python’s esophagus and stomach and shed their eggs in their feces. The eggs are ingested by various small mammals, in which the larvae settle, which serve as intermediate hosts . The larvae migrate to the thoracic and abdominal organs where, particularly in marsupials, third instar larvae can reach considerable length (7–8 cm), even in small hosts. The life cycle ends when the pythons consume the infected intermediate hosts. Humans infected with O. robertsi larvae would be considered accidental hosts , although human infection with any Ophidascaris species has not been previously reported . We present a case of human neural larva migrans caused by O. robertsi infection.

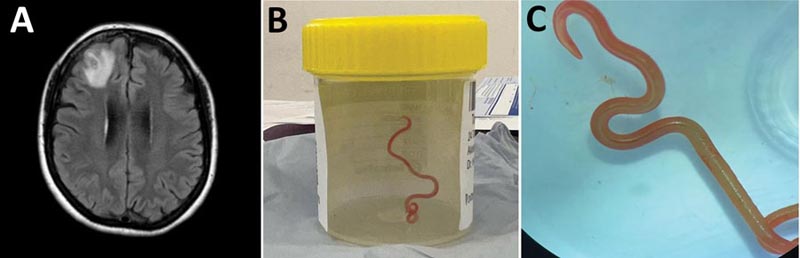

Figure : Human neuronal larva migrans caused by Ascarid Ophidascaris robertsi . Detection of Ophidascaris robertsi nematode infection in a 64-year-old woman from southeastern New South Wales, Australia. A) Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery magnetic resonance imaging of the patient’s brain demonstrates an enhancing lesion in the right frontal lobe, 13 × 10 mm. B) Live third-instar larval form of Ophidascaris robertsi (80 mm long, 1 mm diameter) removed from the patient’s right frontal lobe. C) Live third instar larval form of O. robertsi (80 mm long, 1 mm diameter) under stereoscopic microscope (original magnification ×10). (CDC Source)

The clinical case study

A 64-year-old woman from southeastern New South Wales, Australia, was admitted to a local hospital in late January 2021 after three weeks of abdominal pain and diarrhea, followed by a dry cough and night sweats. He had a peripheral blood eosinophil count (PBEC) of 9.8 × 10 9 cells/L (reference range <0.5 × 10 9 cells/L), hemoglobin 99 g/L (reference range 115–165 g /L), platelets 617 × 10 9 cells/L (reference range 150–400 × 10 9 cells/L) and C-reactive protein (CRP) 102 mg/L (reference range <5 mg/L). Her medical history included diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, and depression . She was born in England and had traveled to South Africa, Asia and Europe between 20 and 30 years earlier. She was treated for community-acquired pneumonia with doxycycline and had not fully recovered.

A computed tomography (CT) scan revealed multifocal lung opacities with surrounding ground-glass changes, as well as hepatic and splenic lesions. Bronchoalveolar lavage revealed 30% eosinophils without evidence of malignancy or pathogenic microorganisms, including helminths. Serological tests were negative for Strongyloides. Screening results for autoimmune diseases were negative. The patient’s diagnosis was eosinophilic pneumonia of unclear etiology; He started taking prednisolone (25 mg/d) with partial symptomatic improvement.

Three weeks later, he was admitted to a tertiary hospital with recurrent fever and persistent cough while taking prednisolone. The lung and liver lesions were 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose avid on positive emission tomography. The lung biopsy sample was compatible with eosinophilic pneumonia but not with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA). Cultures of bacteria, fungi and mycobacteria were negative . Echinococcus, Fasciola and schistosoman antibodies were detected; concentrated and fixed staining techniques did not reveal parasites in fecal samples.

We detected a monoclonal T cell receptor gene rearrangement, suggesting a T cell-driven hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES). Further hematologic and vasculitis investigations were unremarkable. Treatment was started with prednisolone (50 mg/d) and mycophenolate (1 g 2×/d). Because of his travel history, the possibility of false-negative Strongyloides serology, and increased immunosuppression, he received ivermectin (200 µg/kg orally) for 2 consecutive days and a repeat dose after 14 days.

A CT scan performed in mid-2021 showed improvement in the lung and liver lesions, but the splenic lesions did not change. We added mepolizumab (interleukin-5 monoclonal antibody, 300 mg every 4 weeks) in January 2022 because we were unable to reduce prednisolone below 20 mg daily without a flare of respiratory symptoms. When PBEC returned to the normal range, we gradually reduced the dose of prednisolone.

Over a 3-month period in 2022, the patient experienced forgetfulness and worsening depression while continuing prednisolone (7.5 mg/d) and mycophenolate and mepolizumab at the same doses. The CRP was 6.4 mg/L. Brain MRI showed a right frontal lobe lesion with peripheral enhancement of 13 × 10 mm. An open biopsy was performed in June 2022 . We noticed a thread-like structure within the lesion, which we removed; was a live, motile helminth (80 mm long, 1 mm diameter). Circumferential durotomy and corticotomy were performed and no other helminths were found. Histopathology of the dural tissue revealed a benign organized inflammatory cavity with prominent eosinophilia.

We tentatively identified the helminth as a third instar larva of Ophidascaris robertsi on the basis of its distinctive red color, 3 active ascaridoid-like lips, presence of a cecum, and absence of a fully developed reproductive system, in the context of what is known.

A progress CT scan revealed resolution of the lung and liver lesions but unchanged splenic lesions. The patient received 2 days of ivermectin (200 µg/kg/d) and 4 weeks of albendazole (400 mg 2×/d). He was given a course of dexamethasone (starting at 4 mg twice daily) for 10 weeks, while all other immunosuppressants were discontinued. Six months after surgery (3 months after stopping dexamethasone), the patient’s PBEC remained normal. Neuropsychiatric symptoms had improved but persisted.

Conclusions

In this case, the patient resided near an area of a lake inhabited by carpet pythons . Despite not having direct contact with snakes, he often collected native vegetation, warrigal leaves ( Tetragonia tetragonioides ), from around the lake to use in cooking. Our hypothesis is that he inadvertently consumed O. robertsi eggs, either directly from the vegetation or indirectly through contamination from his hands or kitchen equipment.

The clinical and radiological progression of the patient suggests a dynamic process of larval migration to multiple organs, accompanied by eosinophilia in blood and tissues, indicative of visceral larva migrans syndrome. We suspect that the splenic lesions are a separate pathology because they remained stable and were not PET avid, unlike the lung and liver lesions.

This case highlights the difficulty in obtaining an adequate specimen for parasitic diagnosis and the challenging management decisions regarding immunosuppression in the presence of life-threatening HES. Although visceral involvement is common in animal hosts, invasion of the brain by Ophidascaris larvae has not been previously reported. The patient’s immunosuppression may have allowed the larvae to migrate to the central nervous system (CNS). The growth of the third instar larva in the human host is notable, given that previous experimental studies have not demonstrated larval development in domesticated animals, such as sheep, dogs, and cats, and have shown more restricted larval growth in birds and non-native mammals. . than in native mammals.

After we removed the larva from her brain, the patient received anthelmintics and dexamethasone to address possible larvae in other organs. Ophidascaris larvae are known to survive for long periods in animal hosts; For example, laboratory rats have remained infected with third instar larvae for more than 4 years. The rationale for ivermectin and albendazole was based on data from the treatment of nematode infections in snakes and humans. Albendazole has better CNS penetration than ivermectin. Dexamethasone has been used in other human nematode and tapeworm infections to prevent harmful CNS inflammatory responses after treatment.

In summary, this case emphasizes the ongoing risk of zoonotic diseases when humans and animals interact closely. Although O. robertsi nematodes are endemic to Australia, other Ophidascaris species infect snakes elsewhere, indicating that additional human cases may arise globally.

Dr Hossain is an infectious diseases doctor in Australia. His main research interest is parasitology.

Comments

Doctors removed a wriggling roundworm from the brain of an Australian woman in the world’s first known case of human infection with a parasite common in some pythons. The woman, who had been experiencing worsening symptoms for at least a year, is believed to have contracted the infection by foraging and eating grass where a snake had defecated.

"This is the first human case of Ophidascaris described in the world," Dr. Sanjaya Senanayake, a leading infectious disease expert at the Australian National University and Canberra Hospital, said in a university news release. "To our knowledge, this is also the first case involving the brain of any mammal species, human or not."

It is suspected that the 64-year-old woman’s lungs and liver also contained larvae of the roundworm Ophidascaris robertsi . Her symptoms began in January 2021 with abdominal pain and diarrhea, followed by fever, cough, and difficulty breathing.

"In retrospect, these symptoms were probably due to the migration of roundworm larvae from the intestine to other organs, such as the liver and lungs. Respiratory samples and a lung biopsy were performed; however, no parasites were identified in these samples," said Karina Kennedy, director of clinical microbiology at Canberra Hospital.

"At that time, trying to identify microscopic larvae, which had never before been identified as causing human infection, was like trying to find a needle in a haystack," he said in the statement.

As the woman’s symptoms progressed, along with subtle changes in memory and thought processing, she underwent a brain MRI that detected an unusual lesion in the frontal lobe of her brain.

During brain surgery, doctors found the 3.15-inch roundworm. After doctors removed it, still alive and writhing, parasite experts identified it by its appearance. Molecular studies confirmed their identification.

Doctors said the woman probably acquired the infection by foraging and eating spinach-like Warrigal leaves along a lake where a carpet python had shed the parasite through its feces.

Typically, roundworm larvae are found in small mammals and marsupials, which are eaten by carpet pythons, snakes whose markings resemble the patterns of Asian carpets. That allows the life cycle to be completed in the snake.

"There have been about 30 new infections in the world in the last 30 years," Senanayake said. "Of emerging infections globally, around 75% are zoonotic, meaning there has been transmission from the animal world to the human world. This includes coronaviruses." However, the Ophidascaris infection is not transmitted from person to person, so it will not cause a pandemic like COVID-19 or Ebola, Senanayake said. But, he added, both the carpet python and the parasite are found in other parts of the world, so there will likely be cases in the future.

Ophidascaris robertsi is common among carpet pythons, Senanayake said. The parasite normally lives in the snake’s esophagus and stomach, and its eggs are shed in the python’s feces. "Roundworms are incredibly resilient and able to thrive in a wide range of environments," Senanayake said. "In humans, they can cause stomach pain, vomiting, diarrhea, loss of appetite and weight, fever and tiredness."

Safety is especially important when foraging in places where wildlife lives, experts emphasized.

"People who garden or forage should wash their hands after working in the garden and touching foraged produce," Kennedy said. "Any food used for salads or cooking should also be thoroughly washed, and kitchen surfaces and cutting boards dried and cleaned after use."

Infectious and brain disease specialists continue to monitor the patient. "It is never easy or desirable to be the first patient in the world for anything," Senanayake said. "I cannot express enough our admiration for this woman who has shown patience and courage throughout this process."

The researchers’ findings were published in the September issue of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s journal Emerging Infectious Diseases .

What this means for the population Wash picked or grown vegetables thoroughly, especially if they come from areas where wildlife roams, and be sure to wash your hands too. |