Summary Osteoarthritis (OA) is largely a disease of old age, so its prevalence might be expected to be higher today than in the past simply because more people are living longer, especially in Europe, the United States, and other developed nations. However, there is evidence that increasing longevity is probably not the only reason for the high prevalence of osteoarthritis (OA). Wallace et al. tracked long-term trends in the prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the United States using skeletal remains from 2,576 adults over the age of 50, from prehistoric hunter-gatherers to 21st-century urban dwellers. The results show that people who died since the mid-20th century were about twice as likely to have OA as those who died in earlier times, confirming expectations that the disease has become more common. However, this increase in prevalence is evident even after controlling for age in a generalized linear model, indicating the presence of additional important risk factors that have become ubiquitous only in the last half century. The pathogenesis of OA, like all disease etiologies, involves interactions between genes and the environment, but the increase in the prevalence of OA in recent generations indicates that environmental changes are an important factor contributing to the current high prevalence of OA. |

Survive and reproduce in particular environmental conditions

As a result, all organisms adapt to varying degrees to aspects of the environment in which their ancestors existed, including associated diets and physical activity patterns. When environments change, as they inevitably do, ancestral alleles that were once favored by natural selection may no longer match the characteristics of the new environment. Ultimately, as a result of such imbalances , people have an increased susceptibility to diseases that were once rare or non-existent among previous generations. Mismatches between inherited genetic variants and changing environments are a fundamental driver of evolution, but a large body of evidence indicates that such mismatches are becoming more common and severe in humans due to rapid environmental changes related to cultural evolution. of our species.

Although humans have been hunter-gatherers for almost our entire evolutionary history of over 200,000 years, in the last ~12,000 years, a large proportion of the world’s population has shifted from being physically active hunter-gatherers to consuming primarily wild plants and animals. , to being farmers settled in agricultural communities that depend on cereals and other domesticated foods to being postindustrial workers involved in low levels of physical activity and eating highly processed foods . Although these changes in the environment, which have occurred in the blink of an eye in evolutionary time, have brought many benefits and comforts, they are also believed to be responsible for the emergence of a variety of maladjustment diseases .

For example, because of humans’ long evolutionary history as physically active hunter-gatherers consuming a diet high in fiber but low in sugar, the increasing prevalence of type 2 diabetes is thought to be related to recent shifts toward inactivity. physical activity and excessive consumption of foods high in sugar but low in fiber, resulting in a persistent positive energy balance, increased adiposity and chronic low-grade inflammation , which can lead to insulin insensitivity .

However, when considering whether conditions such as OA are examples of maladjustment diseases, caution is warranted, as the concept of maladjustment is often applied to a wide range of health disorders, both in the scientific literature and in the literature. popular press, more as an assumption than as a hypothesis that must be carefully tested. As with the so-called “Paleolithic diet ,” overly simplistic claims about the potential health benefits associated with living more like our ancient ancestors are sometimes made and based on misleading caricatures of past environments12 and the false assumption that humans They evolved to be healthy 9. Clearly, not all specific features of modern environments interact negatively with the genes we inherit, and many environmental alterations can be beneficial , such as antibiotics, refrigeration, or the use of casts for bone fractures. With this caveat in mind, we suggest two main criteria for rigorously testing the mismatch hypothesis for diseases such as OA:

- First, that the disease is more common today than among past populations after taking into account variation in life expectancy.

- Second, that preventable contributors to disease are more common in modern environments.

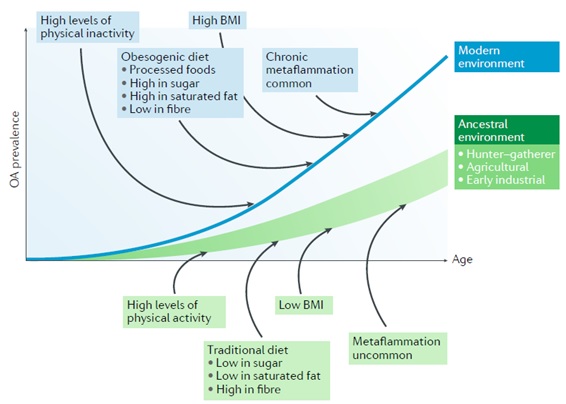

Although OA is not a new disease and has been documented among Paleolithic hunter-gatherers13 and Neolithic farmers14, the study by Wallace et al.3 and previous studies of smaller archaeological samples provide convincing evidence that OA meets the first criterion of a maladjustment disease being more frequent today than in the past. Such studies, however, are retrospective and cannot identify all causes of recent increases in OA. However, evidence that the prevalence of OA in developed countries has skyrocketed over the past half century provides important clues as to which preventable contributors to OA might be responsible, the most conspicuous candidates being obesity, metabolic syndrome, changes in diet and physical inactivity (Fig. 1).

Box: Effect of the obesity epidemic on osteoarthritis prevalence Although it is difficult to precisely quantify how much of the current prevalence of osteoarthritis (OA) is attributable to any given environmental change, the data of Wallace et al.3 provide an indication approximate influence of the obesity epidemic on levels of knee OA in the United States. Among individuals in their skeletal sample for whom BMI at death was documented, 25% of people who died in recent decades were obese, compared with only 1% in earlier times , and people Obese individuals had a 2.2 times higher rate (95% CI 1.6–3.0) of knee OA prevalence than non-obese individuals. These data suggest that obesity today doubles the risk of knee OA to approximately 1 in 4 people over the age of 50, while only 1 in 100 people had a similarly elevated risk of knee OA about half a century ago . Although Wallace et al.3 were limited in their ability to assess the full effect of obesity on the prevalence of knee OA because BMI is a rather inaccurate measure of excess adiposity and BMI was only known as of the time of death. of individuals and not at the time they developed OA, these data provide strong evidence that the recent sharp rise in obesity levels has led to many more people being at increased risk of developing knee OA. |

Figure : Model of osteoarthritis as a maladjustment disease. In all populations, the prevalence of osteoarthritis (OA) increases with age, but the mismatch hypothesis predicts that prevalence at any age is higher in modern environments due to high levels of obesity, chronic metaflammation, physical inactivity, and diets of processed foods rich in sugar and saturated fat and low in fiber .

Misalignment factors

Obesity

Obesity is commonly attributed as a source of maladjustment diseases , since until modern times, most human bodies were rarely, if ever, exposed to high levels of long-term positive energy balance and therefore Therefore, they rarely developed adaptations to deal with the consequences of excess adipose tissue, especially visceral ones. As expected, obesity is a strong and well-established risk factor for OA, especially knee OA. The incidence of knee osteoarthritis among adults ≥ 40 years of age is reported to be approximately three times more common among obese people (BMI ≥ 30) and five times more common among morbidly obese people (BMI ≥ 35) compared to people with a healthy weight (BMI <25). Given such a strong association, the increasing prevalence of OA in developed countries is, to some extent, clearly attributable to the recent growing obesity epidemic (Box 1).

The link between obesity and knee osteoarthritis is especially pernicious because it creates a vicious cycle in which osteoarthritis pain can greatly limit a person’s physical activity, promoting further weight gain and weakening of the joints. the muscles that stabilize and protect the joints, which in turn can exacerbate the pain and progression of OA. Such a negative feedback loop could just as easily be triggered by joint pain as by obesity, but evidence indicates that, in most cases, obesity precedes the onset of OA. The determinant and causal role of obesity in the pathogenesis of OA is further highlighted by evidence that the majority of people with OA who have undergone bariatric surgery to induce weight loss experience a substantial reduction in pain. joint and other symptoms. Evidence suggests that cartilage loss can be slowed if an obese person loses 10% or more of their original weight .

Weight loss can also reduce pain sensitivity and therefore contribute to pain relief. Although the precise mechanisms by which obesity affects the incidence of OA are not fully understood, the oldest and perhaps most intuitive explanation is that obesity creates an abnormal loading environment for weight-bearing joints. Loading per se is not bad for joints, as it is necessary for normal joint development and maintenance, but some loads clearly have the potential to damage cartilage and other joint tissues and therefore increase susceptibility to osteoarthritis, a fact highlighted by the strong link between traumatic injuries and OA.

The added body weight associated with obesity increases the magnitude of axial loads supported by weight-bearing joints, which may impart some of the risk of OA caused by obesity. Among people with varus malalignment of the knee , these large magnitude loads could be especially harmful, as they can magnify knee adduction moments . Additionally, low muscle strength relative to body weight can reduce the ability of transarticular muscles to absorb impact and increase the speed and variability of joint loading.

Mechanoinflammation and metainflammation

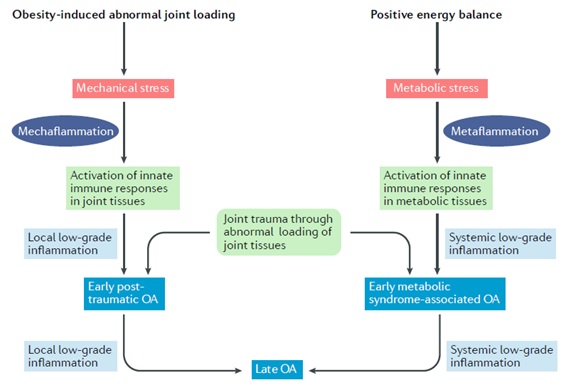

A compromised ability to stabilize joints could cause forces to be concentrated in regions of the joints that are not adequately adapted for such loads and are therefore vulnerable to damage. The primary result of aberrant cartilage loading is damage to the cartilage matrix structure of collagen fibrils and proteoglycans. Cartilage degradation caused by abnormal loads may occur to some extent through wear and tear, but evidence suggests that the primary effect of such loads is to stimulate the production of metalloproteinases by chondrocytes and activate these proteins in the matrix. Abnormal loads activate mechanoreceptors on the surface of chondrocytes, which, in turn, activate intracellular signaling pathways (e.g., mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) or nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB)) and the production of proinflammatory and catabolic mediators. Matrix fragments released into the joint cavity can elicit synoviocyte and macrophage responses and further release these proinflammatory and catabolic mediators , a process we refer to as mechanoinflammation 39 (Fig. 2).

Mechanical factors are likely not the only contributors to obesity-induced OA, as obesity increases the risk of OA not only in weight-bearing joints but also in non-weight-bearing regions such as the hands . The association between obesity and OA is generally stronger for weight-bearing than non-weight-bearing joints, but this difference in susceptibility between joints is evidence that the effect of obesity on OA involves complex interactions. between mechanical and systemic factors . Although much remains to be learned about these systemic factors, evidence indicates that a predominant source is adipose tissue , which produces and releases cytokines (including adipokines) into the bloodstream, many of which (such as IL-1, IL-6 , IL-8, IFNγ, TNF, leptin and resistin) promote chronic low-grade inflammation , also called metainflammation , for which the body is not well adapted (fig. 2).

Several of these cytokines have been experimentally shown to play an important role in the initiation of OA. The adipokine leptin appears to be especially important in the onset of OA, as age-related knee OA does not occur in obese leptin-deficient mice. The most direct route by which high levels of leptin and other cytokines in the bloodstream affect OA is by diffusing into the synovial fluid and activating proteolytic enzymes locally, such as matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MMP1), MMP3 and MMP13 which can trigger matrix degradation in cartilage and other joint tissues. However, obesity-induced metainflammation may also affect OA more indirectly by modulating other critical metabolic factors, as discussed in the next section.

Figure 2 | Mechanoinflammation versus metaflammation . Both osteoarthritis (OA) and obesity begin with activation of the innate immune system , which is produced by local stimulation of joint tissues experiencing abnormal loading or systemic stimulation of adipose tissue. Activation of innate immune responses can lead to two types of low-grade inflammation, mechanoinflammation and metainflammation . Low-grade inflammation, in turn, weakens joint tissues, increasing their vulnerability to damage from subsequent loading and the onset of OA.

Metabolic syndrome

Another common source of maladjustment diseases that also arises from excessive and long-term positive energy balance is metabolic syndrome, which is defined by a group of cardiometabolic factors that commonly accompany obesity, including central adiposity, dyslipidemia, levels of altered fasting glucose and high blood pressure. People with metabolic syndrome are at increased risk for a variety of health disorders, especially cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and some types of cancer. A large body of evidence indicates that metabolic syndrome was once a rare (almost non-existent) disease in non-industrial populations. Given the increasing prevalence of metabolic syndrome in developed countries and an association with obesity, it is not surprising that metabolic syndrome has been hypothesized to be an important risk factor for OA .

Adipose tissue-induced metaflammation is almost always associated with metabolic syndrome and strongly affects metabolic dysregulation underlying multiple metabolic components . In turn, these individual components of the metabolic syndrome could affect the onset or progression of OA. For example, experimental evidence suggests that hyperglycemia may have adverse effects on chondrocyte metabolism, and type 2 diabetes may alter the structure of extracellular matrices, causing enrichment of advanced glycation end products (AGEs). In cartilage, AGEs stiffen the matrix, preventing optimal joint cushioning under mechanical loading. Furthermore, AGEs can signal chondrocytes through specific AGE receptors to increase the synthesis of metalloproteinases and should therefore eventually lead to further degradation of the cartilage matrix. Oxidized LDL , a pro-inflammatory peroxidized lipid detected at high concentrations in the plasma of patients with metabolic syndrome, can stimulate the production of reactive oxygen species by chondrocytes, driving matrix degradation.

High blood pressure could also be involved in the pathogenesis of OA due to the induction of downstream tissue ischemia . If ischemia affects the blood vessels of the subchondral bone, nutritional exchange between the subchondral bone and cartilage could be compromised, leading to altered metabolism of joint cells. However, despite experimental evidence of multiple potential pathways linking metabolic syndrome and OA, data from human studies are conflicting , and most studies do not show an association of metabolic syndrome with knee OA. after taking into account BMI. For example, in a study of 991 people, metabolic syndrome was strongly associated with incident knee OA, but after controlling for body weight, the associations disappeared. However, other studies have found that hand OA (but not knee OA) is strongly associated with metabolic syndrome even after adjusting for body weight.

Interestingly, people with high blood pressure have been shown to have an elevated risk of knee OA regardless of obesity , and the prevalence of OA was higher among people with type 2 diabetes than among people without diabetes, regardless of differences in weight. Additionally, an MRI study indicates that patients with type 2 diabetes have accelerated degeneration of the knee cartilage matrix compared to people without diabetes, even after correcting for ethnicity, age, sex, baseline BMI, and severity of OA measured by the initial Kellgren-Lawrence score. Although experimental research and some human studies provide evidence that individual components of the metabolic syndrome (other than adiposity) contribute to the pathogenesis of OA, more data are needed to resolve the extent to which the current prevalence of OA is attributable to modern increases in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome.

Dietary changes

The increasing prevalence of OA in developed countries raises the question of whether dietary changes cause imbalances that contribute to OA. Modern diets in many developed countries differ from those of previous generations in that they are substantially more energy-dense and processed, with added sugar, salt, and saturated fat, but less fiber, fresh fruits, and vegetables . These dietary changes almost certainly affect the risk of OA by promoting a prolonged positive energy balance and excess adiposity, but also perhaps by increasing the likelihood of hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, and arterial hypertension . However, in addition to promoting metabolic dysregulation, modern dietary changes may affect OA risk in other ways. An additional dietary factor of particular relevance is a reduced intake of antioxidants . Reactive oxygen species are involved in chondrocyte senescence, extracellular matrix degradation, synovial inflammation, and subchondral bone disruption.

Diets in many developed nations are characterized by an increase in the ratio of pro-inflammatory omega-6 fatty acids and anti-inflammatory omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids . However, evidence that this imbalance contributes to disease remains a disputed point of debate. In one study, adding omega-3 fatty acids to the diet reduced the severity of post-traumatic OA in mice and limited concomitant synovitis, while in another study, enriching the diet with omega-3 fatty acids did not reduce the occurrence of OA. knee in mice.

In humans, the effect of omega-3 fatty acid supplements in OA trials has not been reported to affect joint pain. Additionally, sulforaphane, an isothiocyanate abundant in broccoli , decreased the severity of OA in mice, possibly by protecting against reactive oxygen species damage; There are now plans to test broccoli consumption in an OA clinical trial. There is conflicting evidence regarding the effect of antioxidant vitamin C on OA in humans, with experiments in mice, rats and guinea pigs showing that vitamin C may increase the risk of OA. On the other hand, vitamin K , present in green leafy vegetables such as spinach, kale, and broccoli, is a necessary cofactor for the γ-carboxylation of some calcium-binding proteins, including the matrix protein gla, an inhibitor of vitamin K-dependent mineralization expressed in human articular cartilage.

Many observational studies in humans have reported that vitamin K deficiency increases the risk of OA, but there have not yet been clinical trials testing vitamin K treatment. Experimental studies point to other dietary factors that are potentially implicated in the OA but have not yet been carefully examined in human studies (Fig. 3). Some groups have shown that high-fat dietary overload can increase the severity of post-traumatic osteoarthritis in mice and rats. Interestingly, for the same amount of calories, the severity of OA was exacerbated with a diet rich in saturated rather than unsaturated fatty acids.

Obesity and aging are associated with intestinal dysbiosis that can cause chronic age-related metabolic diseases. The role of diet in modulating the composition and metabolic activity of the intestinal microbiome is now recognized. Diffusion of biologically active metabolites (such as acetate, propionate and butyrate) and lipopolysaccharide, a constituent of the microbial cell wall, from the intestine to the bloodstream related to increased intestinal permeability and dysbiosis in patients with obesity is associated with inflammation low-grade systemic . Although evidence that these dysbiosis-derived metabolites have a direct pathophysiological role in OA is lacking, the results of some experimental studies are consistent with this hypothesis.

An important dietary factor that modifies the intestinal microbiota is fiber ; Changes in the gut microbiome could be related to the lack of fiber in the modern diet. In two cohorts, volunteers in the highest quartile of total fiber intake had lower rates of new-onset symptomatic OA than those in the lowest quartile of total fiber intake. In fact, the higher the fiber intake, the less knee pain OA patients experience . Fiber intake has not yet been tested as a treatment in human OA trials. Animal studies also suggest that the gut microbiota affects OA; for example, a reduction of Bifidobacterium spp. in obese mice has been associated with increased migration of macrophages to synovial tissue, accelerating OA, while dietary supplementation with oligofructose, a nondigestible fiber, was associated with joint protection in obese mice.

Physical inactivity

Mechanical loading plays a major role in almost all cases of OA, and since physical activity is the most common source of joint loading and is an environmental factor that has changed in the modern world, any consideration of OA as a disease of imbalance requires examining changes in physical activity patterns. As already noted, an important and well-established risk factor for knee osteoarthritis is joint trauma , especially tears of the anterior cruciate ligament and meniscus , which can lead to abnormal stress gradients and excessive focal stress within the cartilage.

Therefore, it has been hypothesized that increased participation in sports and other athletic activities that frequently cause these types of injuries is the basis for the current high levels of OA. However, this hypothesis is conjectural , given that previous generations, particularly prehistoric populations, almost certainly practiced high levels of moderate and vigorous physical activity and yet had a lower prevalence of OA.

Whether people today are, on average, more susceptible to injuries and post-traumatic osteoarthritis than in the past is highly speculative. Although trauma unquestionably increases the risk of OA, a more likely contributor to the increased prevalence of OA is physical inactivity , which has become epidemic in recent decades, especially in many developed nations. Pathways by which physical inactivity may increase the risk of OA include indirect promotion of obesity and metainflammation, depression, or telomere shortening (Fig. 4).

However, physical inactivity could also directly contribute to the pathogenesis of OA. Because the musculoskeletal system, like many physiological systems, evolved to require biophysical stimuli from the environment to adjust capacity to demand, the mechanical loads generated by activity are critical to the development and maintenance of optimal muscle structure and strength. joint tissues and the muscles that surround them . Additionally, a reduction in loading as a result of a physically inactive lifestyle could cause the formation of weaker, less stable joints that are more susceptible to damage and deterioration.

In other words, physical inactivity leads to an absence of normal demand , so individuals are unlikely to achieve or maintain normal joint capacity. To illustrate this ’use it or lose it’ principle in cartilage, patients with paralyzed limbs show marked thinning of knee cartilage, while MRI studies have shown that people who regularly participate in weight-bearing exercise maintain a thicker cartilage, and in one study, these individuals were even observed to have fewer cartilage defects than physically inactive people. Animal experiments have yielded similar findings: disuse experiments ( e.g., rodent limb immobilization or unloading) consistently demonstrate multiple catabolic effects on joint tissues, including thinning of all cartilage layers, decreased proteoglycan content of cartilage due to increased expression of metalloproteinases and demineralization of subchondral bone due to activation of osteoclasts.

In contrast, a meta-analysis of exercise in several animal species showed that, compared to animals with a moderate daily exercise regimen, non-exercising control animals had thinner knee cartilage with higher aggrecan content. low. Thinner cartilage with lower aggrecan content is not necessarily osteoarthritic cartilage (for example, paralyzed limbs rarely develop OA), but it is biomechanically vulnerable cartilage . Even if physical inactivity is detrimental to joint health, this does not mean that all forms of physical activity are beneficial for joints. As already discussed, some types of loading can threaten the integrity of joint tissues, and loads that are extreme or abnormal , whether in terms of magnitude, frequency, or some other parameter, are produced by active lifestyles through of occupation (e.g., jobs that require frequent knee flexion) or recreation (e.g., sports injuries) can culminate in damaged joints that are more prone to OA.

Therefore, the risk of OA is likely increased by both extreme physical inactivity and activity . However, although considerable clinical and research attention has been paid to the potential negative consequences of some types of physical activity for joint health, more attention should be devoted to understanding the extent to which declines in physical activity underlie the high levels of OA today.

Conclusions

Although the causes of the high and increasing prevalence of OA are not yet fully understood, an important conclusion of this article is that OA fits the criteria of a mismatch disease in that the current prevalence of OA appears to be attributed in part to environmental risk factors that have been amplified in the modern world. These factors likely include obesity, metabolic syndrome, dietary changes, and physical inactivity . An even more important conclusion is that, although the risk of OA is influenced by intrinsic factors such as age and genetics, OA is in part a maladjustment disease affected by modifiable factors , indicating substantial potential for prevention. This is a critical idea, given that available nonsurgical treatments for OA only provide symptom relief and there are no disease-modifying medications.

In summary , although OA may seem primarily a disease of old age , from an evolutionary perspective, it is not age per se that causes the disease but rather an accumulation of joint tissue deterioration that arises from interactions between the genes we inherit from our ancestors and the environments, many of them novel but modifiable, that we encounter as we age. Due to human evolutionary origins as physically active hunter-gatherers outside of energy balance, human joints likely evolved to require routine mechanical loading in the absence of adiposity-induced metaflammation to grow and function optimally with age.

However, even if OA is in part a maladjustment disease, the disease would not stop occurring even if everyone on the planet adjusted their lifestyles to better suit the conditions to which the human musculoskeletal system is adapted. As the incidence of OA in prehistoric populations attests, trauma and other risk factors have always predisposed some people to OA. However, based on the available evidence reviewed here, it seems unlikely that the OA epidemic will stop without at least beginning to reverse the decline in physical activity levels and the quality of our diets, along with concomitant effects on obesity and metabolic dysregulation. How to promote such lifestyle changes is a major challenge.