| Highlights |

|

| Summary |

The human circadian system plays a vital role in many physiological processes, and circadian rhythms are found in virtually all tissues and organs. Disruption of circadian rhythms can lead to adverse health outcomes.

Evidence from recent population-based studies was reviewed because they represent real-world behavior and may be useful in developing future studies to reduce the risk of adverse health conditions, including cardiovascular disease, obesity, and diabetes mellitus, that may occur due to circadian disruption. An electronic search was conducted in PubMed and Web of Science (2012-2022). The selected articles were based on specific inclusion and exclusion criteria.

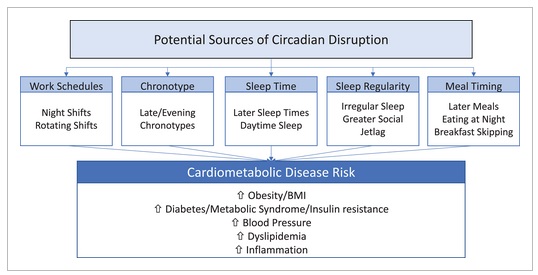

Five factors that can disrupt circadian rhythm alignment are discussed: shift work, late chronotype, late bedtime, sleep irregularity, and late mealtime .

Evidence from observational studies of these circadian disruptors suggests potential detrimental effects on cardiometabolic health, including increased BMI/obesity, increased blood pressure, increased dyslipidemia, increased inflammation, and diabetes.

Future research should identify specific underlying pathways to mitigate the health consequences of shift work. Additionally, optimal sleep and eating schedules for metabolic health can be explored in intervention studies. Finally, it is important to manage the timing of external environmental cues (such as light) and behaviors that influence circadian rhythms.

| Importance of the study |

| What is already known? |

|

| What does this review contribute? |

|

Circadian rhythms or biological clocks are endogenous regulators located in cells or organisms responsible for the coordination of physiological and behavioral activities, allowing organisms to adapt to a changing environment within a 24-hour cycle.

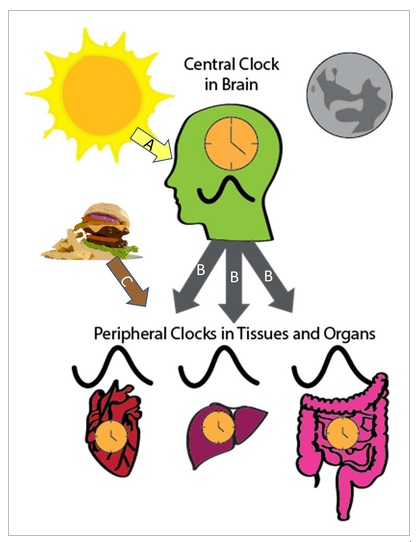

It is believed that the main role of this circadian system is to organize physiological processes temporally in order to anticipate periods of activity and rest. The rhythms of these processes are controlled by internal "clocks," with a central clock located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus, which serves as a conductor for clocks found in almost all tissues of the body. The ubiquitous nature of these clocks throughout the body attests to the importance of these rhythms for health.

Maintaining synchrony is key to optimal health, and this includes synchrony between internal clocks and the external world, as well as synchrony between all internal clocks.

Figure 1

|

| The circadian system is hierarchical with a central clock in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus and peripheral clocks in tissues and organs throughout the body. The main time signal, which synchronizes the central clock, is light (Arrow A), while peripheral clocks are synchronized through several pathways. The central clock regulates the circadian rhythms of peripheral clocks through several mechanisms (arrows B ), such as the control of body temperature, the activity of the sympathetic nervous system and hormones, such as melatonin. Synchronization of peripheral clocks can also be synchronized via power (arrow C). |

The rhythms are synchronized with the outside world mainly through light signals that reach the suprachiasmatic nucleus through the eye, by the retinal ganglion cells. The central clock, in turn, regulates peripheral clocks through several mechanisms, including the control of body temperature rhythms, autonomic nervous system activity, and various hormones, such as cortisol and melatonin.

However, peripheral clocks can also be synchronized through other signals, including feeding and fasting.

Therefore, chronic disruption of the circadian rhythm, resulting from factors such as night shift work, irregular sleep schedules, or meal timing, may contribute to the harmful effects related to chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases ( CVD), cancer and diabetes.

This review focuses on observational studies that examine health and behavior in real-world settings to determine whether there are associations between habitual behaviors and health. Observational evidence for the association between markers of potential circadian disruption and cardiometabolic outcomes is summarized. Certain behaviors and environmental exposures, such as light, can influence the functioning of central and peripheral clocks and lead to circadian disruption.

| Shift work |

Shift jobs, which often involve changing sleep and meals between night and day, can be an extreme form of circadian disruption. Other factors that can affect circadian rhythm alignment include chronotype, meal timing, and sleep regularity and timing. Observational studies have found that rotating or night shift workers (evening chronotype), sleep schedule, sleep irregularity, and meal timing may have adverse effects on cardiometabolic outcomes.

Figure 2

It is important to note that observational studies do not imply causality; however, an association between these factors and cardiometabolic diseases highlights their importance for future research and public health.

| Methods |

PubMed and Web of Science were searched. We included peer-reviewed studies in humans that were published between 2012 and 2022. Only studies published in English with adult participants were analyzed.

| Results and discussion |

> Shift work

Shift workers have work schedules outside of traditional hours (9 a.m. to 5 p.m.). People classified as shift workers have morning, night, rotating and/or evening schedules. Shift work disrupts the normal sleep-wake cycle because these workers often have to sleep during the day, which disrupts circadian rhythms and therefore increases the risk of chronic diseases.

Shift workers are often exposed to light that is not natural daylight. Circadian rhythm disruption associated with shift work is a risk factor for CVD, diabetes, obesity, hypertension, sleep and metabolic disorders.

Observational studies have demonstrated an adverse effect of shift work on cardiometabolic diseases and risk factors. For example, meta-analyses have shown that shift workers were approximately 23% more likely to be overweight or obese, had a 14% increased risk of incident diabetes, 11% to 35% more likely to have metabolic syndrome, and a 10% increased risk of metabolic syndrome. more probability of prevalence of hypertension and 30% probability of incident hypertension. A systematic review of 45 epidemiological studies also found that night shift workers had significantly higher systolic and diastolic blood pressure.

Shift work has been associated with some risk factors for cardiometabolic diseases.

A cross-sectional study of women employed in hospitals found that those who worked rotating shifts had a higher cardiometabolic risk score, based on a combination of blood pressure, fasting blood glucose, triglycerides, and waist circumference measurement. This study also demonstrated differences in the diurnal pattern of urinary cortisol levels. Shift workers had lower total 24-hour cortisol production and a flatter pattern over 2 days of urine collection compared with daytime workers.

Differences in lipid levels associated with shift work were also found. A systematic review of 66 articles showed that shift workers, particularly those on the night shift, had higher levels of total cholesterol, increased triglycerides, and lower levels of high-density cholesterol, which are known risk factors for CVD. .

Inflammation has also been associated with shift work. A study among male shift workers found that hypersensitive C-reactive protein (hsCRP), a marker of inflammation, was significantly higher in former shift workers compared to day workers. Similar findings were observed in another study that showed higher levels of hsCRP in female shift workers compared to daytime workers. Another study among nurses showed that those who worked rotating night shifts had a higher level of CRP compared to those who never worked rotating shifts.

However, one study found no relationship between shift work and hsCRP, but a significant relationship between long work hours and higher hsCRP, as well as an interaction effect with low-grade inflammation between long work. and shift work. Inflammation is a risk factor for CVD, type 2 diabetes, and obesity; therefore, chronic inflammation in shift workers may play a role in the onset and progression of these conditions.

Blood pressure levels and diurnal rhythms play an important role in cardiovascular health, as blood pressure levels have a circadian rhythm that can be disrupted by shift work. Blood pressure values are elevated during wakefulness, particularly during working hours compared to non-working periods, and because work periods occur at a biological time (night) in which blood pressure levels should be lower, shift work (especially night work) can affect the normal pattern of daytime blood pressure, leading to an increased risk of CVD. In fact, blood pressure has been shown to be elevated in shift workers compared to day workers.

In shift workers, changes in healthy behaviors, such as diet and sleep, may partially explain the increased risk of cardiometabolic diseases. Shift workers may consume less healthy foods, such as saturated fats and non-alcoholic beverages, compared to day workers, and they eat at night when the body is ready to sleep.

Shift work can contribute to changes in mealtimes, such as eating all day and skipping meals, which can affect appetite-regulating hormones and lead to dysregulation of the internal circadian rhythm, increasing the risk of cardiometabolic diseases. The results of a cross-sectional study showed that shift workers had higher caloric intake (56 kcal/day more) compared to day workers, possibly due to work hours.

Poor sleep quality is another common factor among shift workers, which may partially explain the increased risk of cardiometabolic diseases. The study in nurses showed poor sleep quality in both those who worked rotating shifts and those who did not, with shift work being an independent risk factor for lack of sleep. Poor sleep quality has been associated with increased cardiometabolic risk.

Leading studies show that shift work has an impact on cardiometabolic health, and potential mechanisms could be related to inflammation, impaired blood pressure regulation, or unhealthy behaviors. One limitation to note is that the definition of shift work is not consistent across studies, while different work schedules may vary in the degree of circadian disruption or impairment of cardiometabolic health.

| Chronotypes |

The chronotype is a construct designed to identify the preferred or actual time for activities, such as sleeping.

Chronotype can be assessed using validated standard self-assessment questionnaires. The most common are the Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire, which assesses the preferred timing of behaviors, and the Munich Chronotype Questionnaire, which assesses the actual timing of the behavior, such as sleep. Objective estimates of the timing of sleep, such as wrist actigraphy, can also be used.

Chronotype, particularly if Morningness-Eveningness is used, often groups individuals into morning, evening, and intermediate chronotypes. Morning chronotype individuals are early risers who prefer the earliest hours of the morning and tend to wake up and go to bed early, while nocturnal types wake up and go to bed later and their peak performance occurs later in the day.

Observational studies have linked evening chronotypes to an increased prevalence of several CVD metabolic diseases, including a higher prevalence of diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and CVD. A meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies reported that evening chronotypes were more likely to have diabetes than morning types.

In the Nurses’Health Study 2 , of >64,000 women in the morning type, a slight reduction in the probability of prevalent diabetes was found compared with intermediate chronotypes, but the evening chronotype was not associated with prevalent diabetes. However, in a prospective analysis of 319 participants, with a follow-up period of approximately 2 years, chronotype was not associated with incident diabetes in fully adjusted models.

Analysis of the UK Biobank, with almost 400,000 participants, showed that morning chronotype was associated with a reduced risk of incident CVD and a lower risk of coronary event, over 5 years of follow-up.

Risk factors or subclinical predictors of cardiometabolic disease have also been associated with chronotype. In the meta-analyses of cross-sectional studies mentioned above, compared with morning chronotypes, evening chronotypes showed significantly higher levels of fasting blood glucose, hemoglobin A1c, triglycerides, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, but no significant differences were found in the body mass index (BMI).

One study found that nocturnal chronotype was associated with higher levels of circulating proteins, including plasminogen activator inhibitor 1. The proteins were shown to be related to insulin resistance .

The association between evening chronotypes and the risk of cardiometabolic diseases may be due to environmental and behavioral factors. For example, people with evening chronotype may consume diets of poorer quality and higher calorie content compared to morning or intermediate chronotypes, and less physical activity, which could lead to poor cardiovascular health.

Nocturnal chronotypes are also exposed to light at inopportune hours, which can lead to circadian disruption. Chronotype influences sleep and meal times, which are also associated with cardiometabolic health. In a study of 872 middle-aged to older adults, people with an evening chronotype had a later sleep and eating schedule compared to those with an earlier chronotype. Two studies that examined the combination of chronotype and shift work did not find a significant association.

Overall, observational findings suggest that later /evening chronotypes are associated with adverse health outcomes compared to early/morning chronotypes . However, more prospective studies are needed. On the other hand, it is necessary to identify the underlying mechanisms. It may be that the health risks associated with the evening chronotype are due to a mismatch with the preferred chronotype and one’s social obligations, leading to unhealthy or inappropriately timed behaviors.

| Sleep schedule and variability |

Sleep timing (the time of day sleep occurs) can lead to circadian disruption, particularly if it occurs at a time that conflicts with the biological clock. Sleep-wake patterns can influence central clock synchronization, particularly through alterations in light exposure, which is reduced while people are sleeping. On the other hand, an irregular sleep schedule could lead to circadian disruption due to irregular exposure to these timing cues.

Of course, sleep schedule and regularity are related to the characteristics described above, such as shift work and chronotype, and there will be some overlap between these concepts. However, some studies have specifically examined sleep schedule and regularity in relation to cardiometabolic risk factors.

Likewise, going to bed later has been associated with worse cardiometabolic health profiles.

For example, a large observational study of Hispanic/Latino adults found that sleeping and waking later was associated with greater estimated insulin resistance and higher measures of systolic and diastolic blood pressure.

A systematic review reported that some studies observed significant associations between late sleep timing or greater variability in timing and higher rates of diabetes and metabolic syndrome, greater weight gain and adiposity, and more cardiometabolic risk factors. . However, not all studies reviewed observed significant associations.

It is worth noting that some studies observed gender differences in these associations, which emphasizes the importance of doing analyzes stratified by gender. Finally, in patients with type 1 diabetes it was observed that greater sleep regularity was associated with better glucose control, demonstrating the potential importance of sleep patterns for patient populations.

In the SWAN ( Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation ), a cohort study of women with a mean age of 51 years that examined the associations between sleep regularities and cardiometabolic health, it was found that the average sleep schedule was not significantly associated with BMI or estimated insulin resistance. However, greater sleep schedule variability was associated with higher BMI and estimated insulin resistance. Likewise, in a sample of women >80 years old, the average sleep schedule was not associated with the values of anthropometric measurements, but greater variability in bedtime was significantly associated with a higher BMI, higher percentage of body fat and lower percentage of lean mass.

In adults >55 years of age with a higher risk of CVD, greater sleep variability was associated with a higher prevalence of diabetes, but not with values of anthropometric measurements and glucose control. A prospective analysis of the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) showed that later sleep time variability was associated with more CVD events and incident metabolic syndrome over approximately 5 years of follow-up. This important study, with a cohort of adults of diverse ethnicities, >70 years, will find the existence of significant associations between greater variability in sleep schedule and greater prevalence, incidence or risk of cardiometabolic disease throughout life.

Several metrics have been developed to capture sleep regularity. One is the concept of “social jet lag ,” which refers to the variability of sleep time on work/school days and days off. Studies have reported associations between greater social jet lag and cardiometabolic risk.

For example, one study found that in younger adults (<61 years), greater jet lag was associated with higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome and diabetes/prediabetes, but no association was observed in older adults. However, another study of young adults, ages 21 to 35, found no association between jet lag and anthropometric or blood pressure measures.

Another metric is the Sleep Regularity Index , which assesses an individual’s percentage chance of being asleep or awake at the same 2 time points 24 hours apart . Lower Sleep Regularity Index values have been associated with adverse cardiometabolic outcomes, impaired daytime function, and delayed circadian sleep/wake timing.

Therefore, these metrics may be useful methods to characterize sleep regularity. Irregular sleep patterns could cause circadian disruption due to the inability of biological clocks to accurately synchronize to the light/dark cycle due to inconsistency in timing signals. For this reason, regular sleep schedules should be encouraged to promote optimal health.

| Meal schedule |

Diet plays an important role in prevention and cardiometabolic control.

Although the quantity and quality of the diet are important for health, importance is being given to the timing of meals. Food serves as a synchronizer of peripheral clocks, therefore meal timing can affect circadian rhythms in metabolic organs.

Chrononutrition is the study of the interaction between circadian rhythm and nutrients to influence human health. Recent research has demonstrated the cardiometabolic health benefits of meal timing and duration. This has led to increased interest in a dietary intervention called intermittent fasting, a few times a week (1 to 3 days/week). whereby there is an alternation between fasting and normal eating periods. Time - restricted eating ( TRE) is a form of intermittent fasting in which individuals eat at restricted times (eating window). In that range, nutrient intake is limited to a period of 4 to 10 hours per day, with no overt attempt at caloric restriction or dietary intake.

In some studies, ERT has significantly improved body weight, waist circumference, insulin sensitivity, β-cell function, and blood pressure. However, a randomized controlled trial of ERT did not observe significantly greater weight loss compared to the control group, which ate 3 structured meals per day. However, the intervention group did not start eating until noon (eating window: 12 pm to 8 pm). On the other hand, results from intervention studies have shown that caloric intake decreased when meal duration was reduced; so these beneficial results of intermittent fasting may be the result of lower caloric intake.

In a recent randomized controlled trial, Liu et al. found that people with obesity who were assigned to ERT had no additional benefits in body weight loss or metabolic risk factors compared to those who did daily calorie restriction. An important area of study is whether TRE at specific times of the day has benefits for cardiometabolic health.

Research shows that early intermittent fasting , that is, when the eating window begins earlier in the day, has some health benefits while a later eating schedule has been associated with risk factors for metabolic diseases.

Results from a randomized controlled trial with healthy individuals showed a greater reduction in estimated insulin resistance (assessment of the homeostatic model of insulin resistance) with early intermittent fasting (8 hours; between 06:00 and 15:00: 00 hours) than with midday intermittent fasting (8 hours between 11:00 and 20:00), or the control group (eating ad libitum for more than 8 hours/day).

The results of a recent systematic review of 19 articles suggest that both early (eating window ends before 5:00 p.m.) and late intermittent fasting (eating window begins after 10:00 a.m. and ends before 11:00 p.m.) had similar metabolic effects on the health of study participants.

Consumption of breakfast , the first meal of the day, has often been associated with metabolic outcomes. Frequent breakfast consumption has been associated with a reduced risk of metabolic conditions while individuals who skip breakfast are more likely to have a higher BMI and greater risk of cardiometabolic diseases.

For example, in the Adventist Health Study 2 (n = 50,660; mean follow-up about 7 years), individuals who ate breakfast had a significant decrease in their BMI compared to those who did not eat breakfast.

Furthermore, a meta-analysis of observational studies (n = 15 cohort studies) showed that frequent breakfast eaters (>3 times/week) had a reduced risk of type 2 diabetes, obesity, metabolic syndrome, CVD, and hypertension, in compared to those who consumed breakfast <3 times/week.

Results from a large cross-sectional study, Korea National Health , 2013-2017, and the Nutrition Examination Survey (N = 14,279) showed that morning eating was associated with a decreased prevalence of metabolic syndrome and abdominal obesity in women. Results from a meta-analysis of 9 trials showed higher total caloric intake in breakfast eaters compared to non-breakfast eaters.

The better metabolic results associated with breakfast intake could derive from the action of food as synchronizers of peripheral clocks . Although the "optimal schedule" for food intake may not be well understood , regular breakfast consumption can affect many physiological processes, such as glucose homeostasis and regulation of plasma lipids, which which results in alignment between the central and peripheral clocks.

However, none of these studies evaluated the timing of the internal circadian rhythm, so it would not be possible to find out the best timing for meals. However, these studies suggest a metabolic health benefit from eating early in the morning. Eating late at night can be detrimental to metabolic health and has been associated with increased body fat, which can result in metabolic diseases such as diabetes, obesity, and CVD. Eating late can lead to a misalignment of the central and peripheral clocks, leading to metabolic diseases.

A study by Sakai et al. examined the relationship between late-night dining and glycemic control in people with type 2 diabetes and showed an independent association between late-night dining and higher hemoglobin A1c levels. Another study by Reid et al. showed that eating later and closer to bedtime was associated with higher caloric intake. Furthermore, the results of the KNHANES study showed that eating at night was associated with an increased prevalence of metabolic disorders and a reduced level of high-density cholesterol.

The exact mechanism by which TRE influences circadian rhythms and health is not well understood. It could be that, by consuming a restricted diet, the body uses less glucose and more lipids and ketones, destined for energy expenditure, resulting in better glucose levels and better lipid homeostasis, which can improve metabolic health. On the other hand, although in humans intermittent fasting may not result in ketosis (in the presence of inadequate carbohydrates, the body turns to fat for energy), an increase in autophagy and antioxidant defenses may occur.

The thermic effect of food may explain why a later meal time may influence some risk factors for cardiometabolic diseases. A lesser effect has been observed for foods eaten in the evening compared to those eaten in the morning. This effect may be the result of circadian influence. On the other hand, there are endocrine factors that can peak in humans depending on fluctuations in the time of day. For example, in the morning (7am–8am) during the active phase, there is a spike in cortisol, which regulates the body’s energy and prepares it for the active phase.

Ghrelin is a hormone that increases appetite and peaks at 3 times of the day, i.e. 8 am, 1 pm and 6 pm. Likewise, there is a peak of the hormone leptin at night (7 pm), which It is responsible for decreased appetite and the breakdown of fats. Therefore, consuming meals during the active phase, when there are hormonal peaks, can be beneficial for health.

Diet plays a vital role in health, and matching food intake to your internal circadian clock helps with metabolic health.

New dietary interventions, such as intermittent fasting, may help maintain or improve circadian rhythm alignment, which in turn may lead to the decrease of many metabolic risks.

Despite the health benefits of intermittent fasting and restricted eating, there are some limitations. There is no consensus on the ideal time to eat/fast for the goal of optimal health. Therefore, several studies show heterogeneity in meal timing. Meal timing influences human physiology; therefore, when there is a misalignment between eating/fasting cycles and the endogenous circadian system, health can be affected. Meal timing, including TRE, is a promising novel dietary strategy that is important for cardiometabolic health. More research is needed to understand optimal meal timing and dietary patterns for “circadian” and cardiometabolic health.

| Potential mediators between behavior, circadian disruption and cardiometabolic disease |

To this point, the authors described evidence for associations between several potential circadian disruptors and markers of cardiometabolic health. The mechanisms underlying these associations are not fully understood. The limitation of large observational studies is the lack of direct measurements of the circadian system or circadian phase (i.e., the internal clock schedule).

None of the studies described above directly measured the internal circadian system, such as dim light onset of melatonin or body temperature rhythms. Thus, it is not possible to assess the degree to which circadian rhythms were disrupted. It is assumed that the circadian system is involved in these associations.

| Conclusion |

Circadian rhythms are essential to regulate the state of the physiological processes of the human body.

In the last decade, evidence from several observational studies has demonstrated a link between circadian rhythm disruption and cardiometabolic diseases.

Lifestyle and environmental factors can lead to circadian disruption, but future research should design strategies to minimize exposure to these factors or mitigate their effects when unavoidable (e.g., shift work). As an emerging field, there are many unanswered questions that we hope will be addressed by future studies.

Finally, effective dissemination methods need to be developed to teach the public about the importance of circadian health for overall health and well-being.

| Summary for patients |

Circadian Rhythm and Metabolic Health by David Rakel MD, FAAFP The human body is fascinating. It has programming software that allows it to synchronize with the environment in which it lives. If out of sync, our risk of metabolic dysfunction may increase. I have written a patient handout that you can copy and paste that summarizes the recommendations in this document. > A healthy circadian rhythm We have programming that allows us to synchronize with the environment in which we live. This is called the circadian rhythm. When out of sync, medical research has found associations with obesity, high blood pressure, high cholesterol levels, more inflammation, and an increased risk of diabetes. The circadian rhythm control center is located deep in the brain; Each organ has a circadian rhythm. The brain is primarily influenced by light, while the sensors in our organs respond to eating and fasting. > Exposure to light

> Eating time Chrononutrition is a word that describes how when we eat can influence our circadian rhythm in healthy and unhealthy ways. Fasting and time-restricted eating may improve weight management, in part by influencing hormones that control metabolic health through the circadian rhythm.

|