Many indigenous peoples and local communities around the world lead very satisfying lives despite having very little money. This is the conclusion of a study by the Institute of Environmental Science and Technology of the Autonomous University of Barcelona (ICTA-UAB), which shows that many societies with very low monetary incomes have remarkably high levels of life satisfaction, comparable to those of the rich areas.

High reported life satisfaction among low-income small-scale societies

Meaning

It is often said that money can’t buy happiness , but many surveys have shown that wealthier people tend to report being more satisfied with their lives. This trend could be interpreted as an indication that high material wealth (measured in monetary terms) is a necessary ingredient for happiness. Here we show survey results from people living in small-scale societies outside the globalized mainstream, many of whom identify as indigenous. Despite having little monetary income, respondents frequently report being very satisfied with their lives, and some communities report satisfaction scores similar to those in wealthier countries. These results imply greater flexibility in the means to achieve happiness than what emerges from surveys that examine only industrialized societies.

Summary

Global surveys have shown that people in high-income countries generally report being more satisfied with their lives than people in low-income countries. The persistence of this correlation, and its similarity to correlations between income and life satisfaction within countries, could give the impression that high levels of life satisfaction can only be achieved in wealthy societies.

However, global surveys have generally overlooked small-scale non-industrialized societies, which may provide an alternative test of the coherence of this relationship.

Here we present the results of a survey conducted with 2,966 members of indigenous peoples and local communities in 19 globally distributed sites. We find that numerous populations that have very low monetary incomes report high average levels of life satisfaction, comparable to those in rich countries. Our results are consistent with the notion that human societies can support highly satisfying lives for their members without necessarily requiring high degrees of monetary wealth.

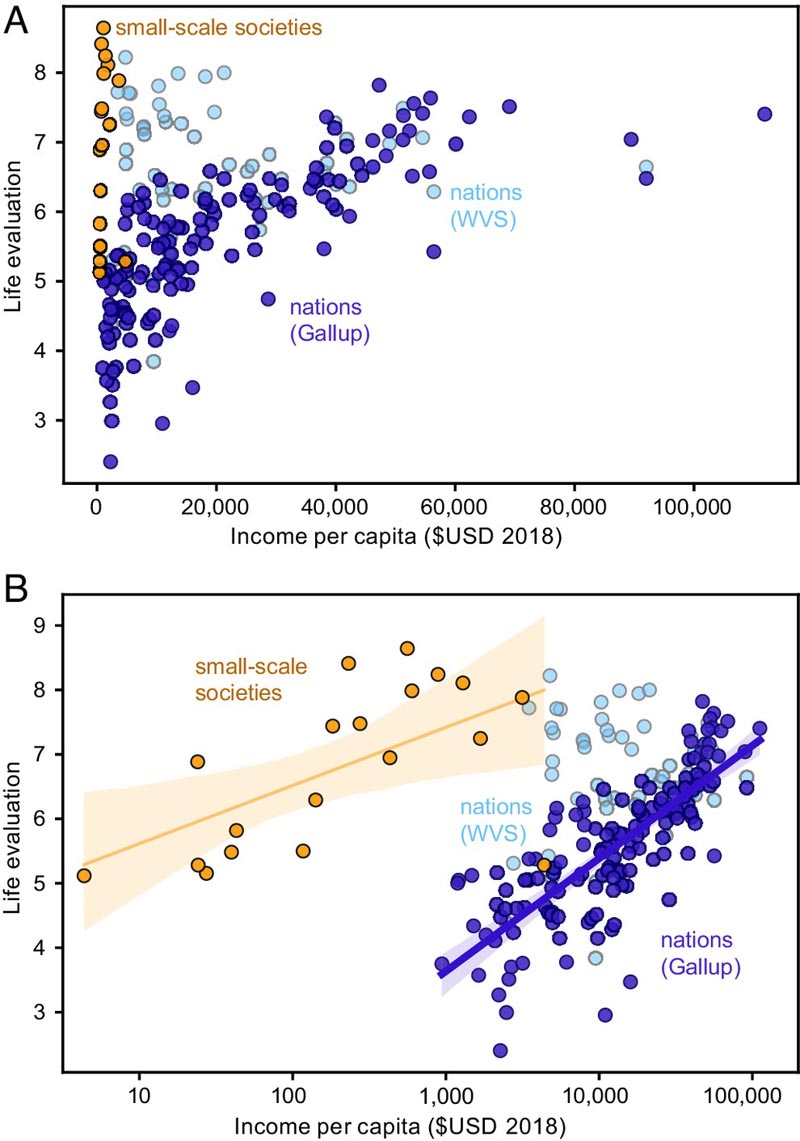

Figure: Life evaluations versus estimated per capita income. Life assessment scores were reported during face-to-face interviews and averaged across populations. Each dark blue circle shows a national average from the Gallup World Poll ( 10 ), with income approximated by GDP per capita. The orange circles show our results for small-scale societies of Indigenous Peoples and local communities with representative incomes estimated from material asset data. Pale blue circles show rescaled national averages from the seventh wave of the World Values Survey ( 35 ). Panel (A) plots the data on linear axes, while (B) shows the same data with income on a logarithmic axis and shows OLS linear regressions within 95% uncertainty envelopes. Linear regression for the WVS data is not significant (P = 0.9) and is therefore not shown.

Comments

Economic growth is often prescribed as a sure way to increase the well-being of people in low-income countries, and global surveys in recent decades have supported this strategy by showing that people in high-income countries tend to report higher levels of life satisfaction than those in low-income countries. This strong correlation could suggest that only in rich societies can people be happy.

However, a recent study conducted by ICTA-UAB in collaboration with McGill University in Canada suggests that there may be good reasons to question whether this link is universal. While most global surveys, such as the World Happiness Report, gather thousands of responses from citizens in industrialized societies, they tend to overlook people in small-scale, marginalized societies, where the exchange of money plays a role. a minimal role in everyday life and livelihoods directly depend on nature.

The research, published in the scientific journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), consisted of a survey of 2,966 people from indigenous and local communities in 19 sites distributed globally. Only 64% of households surveyed had cash income. The results show that "surprisingly, many populations with very low monetary incomes report very high average levels of life satisfaction, with scores similar to those in rich countries ," says Eric Galbraith, researcher at ICTA-UAB and McGill University and lead author of the study.

The mean life satisfaction score in the small-scale societies studied was 6.8 on a scale of 0 to 10. Although not all societies reported being very satisfied (averages were as low as 5.1), four of sites reported average scores above 8, typical of wealthy Scandinavian countries in other surveys, "and this is so even though many of these societies have histories of marginalization and oppression." The results are consistent with the notion that human societies can support highly satisfying lives for their members without necessarily requiring high degrees of material wealth, measured in monetary terms.

"The frequently observed strong correlation between income and life satisfaction is not universal and demonstrates that wealth, as generated by industrialized economies, is not fundamentally necessary for humans to lead happy lives ," says Victoria Reyes-García, ICREA researcher at ICTA-UAB and main author of the study.

The findings are good news for sustainability and human happiness, as they provide strong evidence that resource-intensive economic growth is not necessary to achieve high levels of subjective well-being.

The researchers highlight that although they now know that people in many indigenous and local communities report high levels of life satisfaction, they do not know why . Previous work would suggest that family and social support and relationships, spirituality and connections with nature are among the important factors on which this happiness is based, "but it is possible that the important factors differ significantly between societies or, for example, On the contrary, a small subset of factors dominates everywhere. I hope that by learning more about what makes life satisfying in these diverse communities, I can help many others lead more satisfying lives while also addressing the sustainability crisis" , concludes Galbraith.

Discussion

The surprising aspect of our findings, particularly in comparison with the widely cited Gallup World Poll, is that life satisfaction reported in very low-income communities can equal and even exceed that reported at the highest average levels of material wealth provided by industrial lifestyles. This is at odds with the consensus view, but is consistent with previous cross-cultural studies on subjective well-being that suggest that most people are quite happy by default. It also highlights the dominant role that non-material factors , such as social support and trust, could play in increasing the future happiness of people around the world.

Our findings provide strong empirical support for the argument that achieving high life satisfaction does not require the high rates of material consumption generally associated with high monetary incomes. Rather, they add weight to the importance of identifying the underlying factors that cause people to report high satisfaction with their lives. Non-monetary factors have long been known to be important for well-being; The idea here is that these factors can produce higher levels of satisfaction, at the population level, than is normally thought. Additional research into the factors that support high levels of life satisfaction while maintaining low material requirements, as exemplified by the communities studied here, may provide unexplored strategies for improving the well-being of humans as they navigate planetary boundaries.