Summary

Precipitated by chronic psychological stress, immune system dysregulation, and a hyperinflammatory state, the sequelae of post-acute COVID-19 (long COVID) include depression and new-onset diabetes.

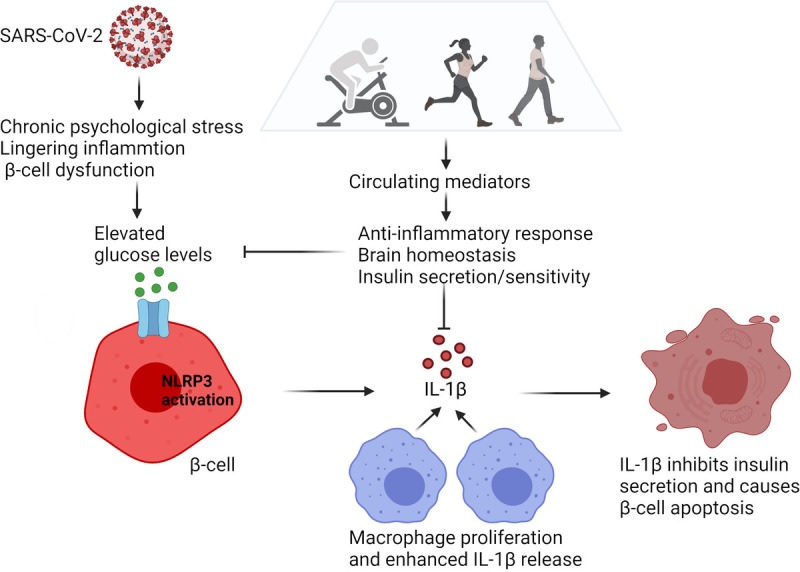

We hypothesize that exercise counteracts the neuropsychiatric and endocrine sequelae of long COVID by inducing the release of circulating factors that mediate the anti-inflammatory response, support brain homeostasis, and increase insulin sensitivity.

Keywords : exercise, COVID-19, psychological stress, immune dysregulation, hyperinflammation

Key points

|

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the pathogen that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and has contributed to millions of deaths worldwide. In some cases, persistent symptoms and the development of sequelae occur 4 to 12 weeks after the onset of acute COVID-19 symptoms (long COVID).

The antibody response is consistent with long-lasting immunity against secondary COVID-19 disease. However, SARS-CoV-2 mRNA and protein are active in the small intestine epithelium of some people almost 6 months after COVID-19 diagnosis.

The underlying pathophysiology of COVID-19 is multifaceted and components appear to be inextricably linked. The variability of clinical disease trajectories in patients with COVID-19 is marked by disparities that exceed commonalities. Therefore, understanding the cellular mechanisms and critically evaluating the convergence between observations becomes necessary to arrive at an informed strategy to manage the risk of long COVID and prevent its escalation.

SARS-CoV-2 binds to the ACE2 receptor expressed on pancreatic β cells and induces cellular damage that can worsen pre-existing diabetes or precipitate the onset of diabetes. Diabetic ketoacidosis typically seen in type 1 diabetes, which is an autoimmune condition, occurs in patients without a diagnosis of pre-existing diabetes weeks or months after resolution of COVID-19. Cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) are elevated in patients with severe COVID-19.

Physical inactivity is associated with a higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes and more severe COVID-19 outcomes.

The odds of a physically inactive person experiencing severe outcomes from COVID-19 exceed those of most chronic diseases (6). We hypothesize that exercise promotes the release of circulating mediators that are critical for the attenuation of long-term neuroendocrine symptoms of COVID-19.

In this review, we present biological insights into the maladaptive stress patterns that predispose people to the clinical depression and glucose dysregulation characteristic of type 2 diabetes. We evaluate the evidence to support our testable hypothesis that exercise can prevent or mitigate the long-term consequences of COVID-19.

The development of hyperglycemia arising from disruption of immune metabolic homeostasis in COVID-19. High glucose levels induced by psychological stress, persistent inflammation, and β-cell dysfunction can lead to activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in pancreatic β-cells. As a result, pro-IL-1β is processed to biologically active IL-1β. IL-1β released from β cells causes recruitment and activation of macrophages, leading to the release of more IL-1β. High local concentrations of IL-1β in the β-cell microenvironment can inhibit insulin secretion and trigger β-cell dysfunction and apoptosis. This leads to further increases in glucose levels, thereby causing autostimulation of IL-1β and establishing a vicious cycle. Exercise induces the release of circulating factors that mediate the anti-inflammatory response, support brain homeostasis, and increase insulin sensitivity. The net effect is the reduction of glucose levels and could be conceived as a remission induction therapy to counteract the after-effects of COVID-19 (graphics program: Biorender). IL-1β, interleukin-1β; NLRP3, NOD-, LRR-, and pyrin domain-containing protein 3.

Neuropathology of COVID-19

Approximately 30% to 40% of patients experience clinically significant anxiety and depression following COVID-19 infection consistent with previous severe coronavirus infections. The likelihood of a new psychiatric illness, such as anxiety and mood disorders, within 90 days of being diagnosed with COVID-19 was a staggering 5.8% in an analysis of 62,354 patients.

Autopsy results show that COVID-19 produces several types of pathological lesions that may contribute to neurological manifestations in patients with COVID-19. Parainfectious conditions, such as postviral autoimmune disorders, have been described in association with a variety of viruses, including coronaviruses. Parainfectious neuropathological processes usually occur after a period of latency following an infectious disease.

A rapidly evolving area with converging evidence suggests that COVID-19 may induce autoimmunity in predisposed individuals.

Whether autoantibodies affect pancreatic β cells will likely be answered by ongoing research on viruses and autoimmunity. Importantly, depression amplifies disability caused by comorbidities such as diabetes by exacerbating physical inactivity and poor treatment adherence to co-prescribed regimens. This interaction exemplifies what occurs with other medical comorbidities of depression. Physical activity may serve to reverse the downward spiral by reducing inflammation and improving symptoms of distress and insulin resistance.

Modulation of allostatic load

The concept of allostasis describes the ability of an organism to maintain homeostatic systems that are essential for life in the face of environmental changes and stressful challenges by actively adapting to predictable and unpredictable events. Allostatic load represents the cumulative impact of physiological wear and tear that arises from chronic exposure to stress and predisposes individuals to disease. Biological systems involved in physiological adaptation to change and stressful events include the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the autonomic nervous system, and the immune system.

HPA Axis Activation

The HPA axis is activated in response to physiological or psychological stressors, inducing the release of the glucocorticoid hormone cortisol from the adrenal gland. Stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system accompanies activation of the HPA axis, resulting in a sudden increase in cytokines including catecholamines and IL-6.

Cortisol release exceeds typical levels in an effort to coordinate a temporary fight-or-flight response and compensate for a possible exaggeration of the immune response. Resolution of the stressful event terminates the response through a negative feedback loop. Cortisol secretion follows a diurnal pattern that helps regulate glucose metabolism and immune response.

Chronic stress can affect the return of these hormonal systems to normal, resulting in an elevation of cortisol, catecholamines, and inflammatory markers.

Psychological stress, depression and type 2 diabetes

Chronic psychological stress occurs when responses to environmental demands are perceived to exceed an individual’s adaptive capacity.

Depression represents a state of greater mental exhaustion than chronic psychological stress, which is a risk factor and component of clinical depression . The risk of type 2 diabetes increases as the psychological burden progressively increases. Although evidence supporting an association between general chronic psychological stress and diabetes risk suggests a positive association, the results are not entirely consistent due to variation in study design and focus.

However, depression predisposes people to the onset and progression of type 2 diabetes. It is estimated that at least 10% to 15% of people with type 2 diabetes experience depression. Additionally, depression is twice as likely to be present in people with type 2 diabetes compared to those without type 2 diabetes, and people with depression have a 1.5 times higher risk of type 2 diabetes.

Chronic exposure to elevated levels of cortisol affects the structure and function of glucocorticoid receptors and brain regions necessary to process emotional and cognitive functions. The biological association between depression and type 2 diabetes appears to be related to dysregulated hypercortisolemia consistent with an overactive HPA axis that drives visceral adiposity and creates deficits in insulin sensitivity and secretion.

Glycemic control and related health outcomes, such as weight gain, adherence to therapeutic regimens, and vascular complications, worsen when type 2 diabetes is accompanied by depression. Type 2 diabetes and depressive symptoms predispose to each other, suggesting a bidirectional link.

Exercise in post-acute COVID-19

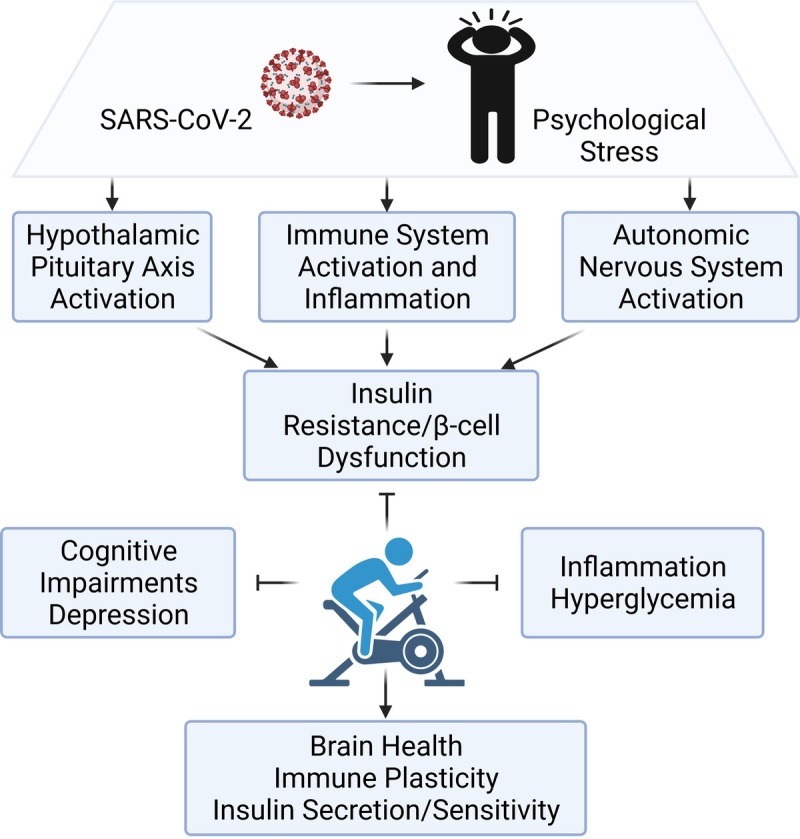

The exercise targets the neuropsychiatric and endocrine sequelae of long COVID precipitated by increased allostatic load arising from chronic psychological stress, dysregulation of the immune system, and stimulation of a hyperinflammatory state. Disruption of allostasis if left untreated leads to glucose dysregulation and development of diabetes, which may tip the balance toward clinical depression due to its bidirectional relationship.

Lenze et al. demonstrated that the antidepressant fluvoxamine, which has a high affinity at the sigma-1 receptor, prevents progression to severe disease after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Sigma-1 receptors play a key role in virus replication, and the resulting endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress can promote the inflammatory cascade through its interaction with the ER stress-responsive protein, inositol-requiring enzyme 1. (IRE1) α. Sigma-1 receptor ligands attenuate the inflammatory response.

Therefore, fluvoxamine, which is a potent sigma-1 receptor agonist, was selected for its effects on regulating inflammatory cytokine production, and its beneficial effects were demonstrated in a randomized placebo-controlled trial of adults in a outpatient setting.

Like fluvoxamine, exercise has antidepressant and immunomodulatory effects that make it imminently suitable for selective prevention in slowing the cascade of events that arise from chronic psychological stress and lead to depression and type 2 diabetes. Importantly that exercise increases peripheral insulin sensitivity in glucose intolerance and type 2 diabetes, measured by the gold standard hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp test.

In patients with pre-existing type 2 diabetes, a blood glucose concentration of 6.4 mmol L−1 was associated with a reduced risk of all-cause mortality and adverse COVID-19 outcomes compared with a blood glucose of 10.9 mmol·L−1. Therefore, maintenance of glycemic control appears to be a judicious recommendation to reduce the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection and its post-acute outcomes. By modulating psychological stress, prolonged inflammation, and insulin sensitivity, exercise constitutes a plausible intervention to prevent or mitigate the long-term endocrine effects of COVID-19.

Dysregulation of physiological adaptation to changes and the modulating effects of exercise. The psychological stress that can occur with COVID-19 activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the autonomic nervous system, and the immune system. A dysregulated and hyperactive HPA axis drives activation of the sympathetic nervous system and an exaggerated immune response that promotes insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction. Exercise helps improve immunosurveillance and reduce inflammation to improve mental health outcomes and glycemic control (graphics program: Biorender).

Comments

While there is no medically recognized treatment for Long COVID, exercise can break the vicious cycle of inflammation that can lead to the development of diabetes and depression months after a person recovers from the virus.

“We know that long COVID causes depression and we know that it can raise blood glucose levels to the point where people develop diabetic ketoacidosis, a life-threatening condition common among people with type 1 diabetes,” said Candida Rebello, Ph. .D., research scientist at the Pennington Biomedical Research Center. “Exercise can help. “Exercise counteracts the inflammation that leads to elevated blood glucose and the development and progression of diabetes and clinical depression.”

It is unclear how many people suffer from Long COVID. But estimates range from 15 to 80 percent of people infected. Based on those numbers, up to 1 million Louisiana residents may be suffering from Long COVID.

Long COVID causes what the Centers for Disease Control describes as “a constellation of other debilitating symptoms,” including brain fog, muscle pain and fatigue that can last months after a person recovers from the initial infection.

“For example, a person may not get seriously ill from COVID-19, but six months later, long after the cough or fever has gone, they develop diabetes,” Dr. Rebello said.

One solution is exercise. Dr. Rebello and her co-authors describe her hypothesis in “ Exercise as a Moderator of Persistent Neuroendocrine Symptoms of COVID-19 ,” published in the journal Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews.

“You don’t have to run a mile or even walk a mile at a fast pace,” Dr. Rebello said. “Walking slowly is also exercising. Ideally, you should do a 30-minute exercise session. But if you can only do 15 minutes at a time, try doing two 15-minute sessions. If you can only walk 15 minutes once a day, do it. The important thing is to try. It doesn’t matter where you start. You can gradually increase up to the recommended level of exercise.”

“We know that physical activity is a key component to a healthy life. “This research shows that exercise can be used to break the chain reaction of inflammation that leads to high blood sugar levels and then the development or progression of type 2 diabetes,” said Pennington Biomedical CEO John Kirwan, Ph.D., who is also a co-author of the paper.

Conclusions The risk of severe SARS-CoV-2 infection and mortality is among the highest in patients with pre-existing type 2 diabetes. Modulation of allostatic load resulting from COVID-19, as demonstrated by neuropsychiatric sequelae, is implicated in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes, while diabetic ketoacidosis is the result of uncontrolled glycemia. Exercise modulates key persistent features of a SARS-CoV-2 infection that promote elevations in blood glucose concentrations, including inflammation and stress. By modulating blood glucose concentrations, exercise can be used to break the vicious cycle of β-cell inflammation leading to hyperglycemia and thus prevent the development or progression of type 2 diabetes. |