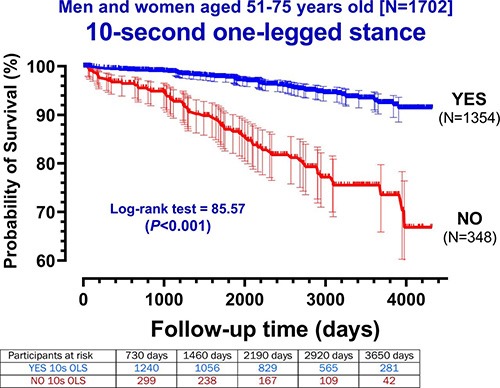

Summary Goals Balance declines rapidly after the mid-50s, increasing the risk of falls and other adverse health outcomes. Our objective was to evaluate whether the ability to complete a 10-second single-leg stance (10-second OLS) is associated with all-cause mortality and whether it adds relevant prognostic information beyond ordinary demographic, anthropometric, and clinical data. . Methods Anthropometric, clinical, vital status data, and 10-s OLS were evaluated in 1,702 individuals (68% men) aged 51 to 75 years between 2008 and 2020. Log-rank and Cox models were used to compare survival curves. and the risk of death based on the ability (YES) or inability (NO) to complete the 10-s OLS test. Results Overall, 20.4% of individuals were classified as NO. During a median follow-up of 7 years, 7.2% died, with 4.6% (YES) and 17.5% (NO) in the 10-s OLS. Survival curves were worse for NO 10-s OLS (log-rank test = 85.6; p < 0.001). In an adjusted model incorporating age, sex, body mass index, and comorbidities, the HR for all-cause mortality was higher (1.84 (95% CI: 1.23 to 2.78) (p<0.001)) for individuals NO. The addition of 10 s OLS to a model containing established risk factors was associated with significantly improved mortality risk prediction, as measured by differences in −2 log odds and improved integrated discrimination. Conclusions Within the limitations of uncontrolled variables such as recent history of falls and physical activity, the ability to successfully complete the 10-s OLS is independently associated with all-cause mortality and adds relevant prognostic information beyond age. , sex and various other anthropometric and clinical data. There is potential benefit to including the 10-s OLS as part of the routine physical examination in middle-aged and older adults. |

Body position in the 10-s single-leg stance test.

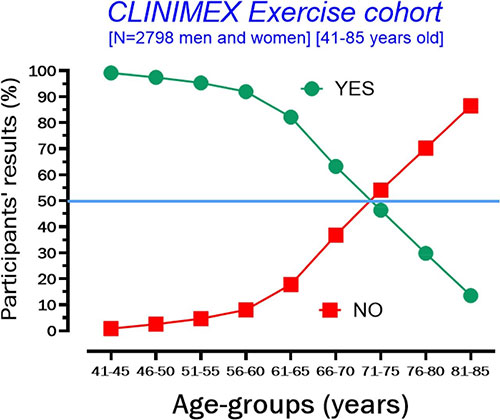

YES = ability or NO = inability to complete the 10-s one-leg stance test according to age groups. This figure includes information from individuals from a broader age range than that included for analysis in this study as mentioned above.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of participants aged 51 to 75 years divided by ability (YES) and inability (NO) to complete the 10-s single-leg stance test.

Discussion

Each year, an estimated 684,000 people die from falls worldwide , of which more than 80% are in low/middle-income countries. While good levels of balance are known to be relevant to many activities of daily living, there is considerable evidence that loss of balance is also detrimental to health and some exercise interventions can improve balance. However, it is currently unclear whether the results of repeated 10-s OLS testing would be amenable to intervention, i.e., exercise or balance training. , and whether changes in 10-s OLS over time would influence mortality risk.38

In our 13 years of clinical experience routinely using the 10 s OLS static balance test in adults with a wide age range and various clinical conditions, the test has been remarkably safe, well received by participants, and most importantly , easy to incorporate into our usual practice since it requires less than 1 or 2 minutes to apply.

Forecast information

The ability to complete the 10-s OLS test begins to progressively decline with aging, reducing by approximately half at each subsequent 5-year age group interval. Put another way, participants in the oldest age group (71 to 75 years) were more than 11 times more likely to answer NO compared to those 20 years younger and in the youngest age group in the study (51 to 55 years).

Ability to complete the 10-s OLS tended to show both a ceiling and a floor in terms of an age profile, with very few (<1%) younger participants (<45 years of age) failing and relatively few participants over 80 years old. years capable of completing the test (see online supplementary material).

Univariate analysis indicated that a 10-s NO OLS response was significantly and directly associated with age, a high waist-to-height ratio, and the prevalence of diabetes mellitus.

Our data show that middle-aged and older participants who were unable to complete the 10-s OLS had poorer survival for a median of 7 years compared to those who were able to complete the test, with an 84% higher risk of mortality from all causes, even when taking into account other potentially confounding variables such as age, sex, BMI, and clinical comorbidities or risk factors, such as the presence of coronary artery disease, hypertension, obesity, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus.

The utility of the 10 s OLS test for mortality risk assessment is further corroborated by the fact that it provided improvement in mortality risk discrimination using measures including the IDI and the difference in log odds of − 2.

Conclusion

Our study indicates that the inability to complete a 10-s OLS in middle-aged and older participants is associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality and, consequently, a shorter life expectancy.

Comments

Balance test could be included in routine health checks for older adults, researchers say

The inability to stand on one leg for 10 seconds in middle or old age is linked to a near doubling of the risk of death from any cause over the next 10 years, finds research published online in the British Journal of Sports Medicine.

This simple and safe balance test could be included in routine health checks for older adults, researchers say.

Unlike aerobic fitness and muscle strength and flexibility, balance tends to be preserved reasonably well until the sixth decade of life, when it begins to decline relatively quickly, the researchers note.

However, balance assessment is not routinely included in health checks for middle-aged and older men and women, possibly because there is no standardized test for it, and there is little solid data linking it to different clinical outcomes. of the falls, they add.

Therefore, the researchers wanted to find out whether a balance test could be a reliable indicator of a person’s risk of dying from any cause in the next decade and, as such, could merit inclusion in routine health checks in the community. adulthood.

The researchers drew on participants from the CLINIMEX exercise cohort study. This was established in 1994 to evaluate associations between various measures of physical fitness, exercise-related variables, and conventional cardiovascular risk factors, with poor health and death.

The current analysis included 1,702 participants aged 51 to 75 years (average 61) at their first follow-up, between February 2009 and December 2020. About two-thirds (68%) were men.

Weight and various skinfold measurements plus waist size were taken. Details of the medical history were also provided. Only those with stable gait were included.

As part of the checkup, participants were asked to stand on one leg for 10 seconds without any additional support.

To improve the standardization of the test, participants were asked to place the front of their free foot on the back of the opposite lower leg, while keeping their arms at their sides and staring straight ahead. Up to three attempts were allowed with either foot.

In total, about 1 in 5 (20.5%; 348) participants failed the test . The inability to do so increased with age, roughly doubling in subsequent 5-year intervals from ages 51 to 55 onwards.

The proportions of those who could not stand on one leg for 10 seconds were: almost 5% among those aged 51 to 55 years; 8% between 56–60 years old; just under 18% among people ages 61 to 65; and just under 37% between 66 and 70 years old.

More than half (about 54%) of people aged 71 to 75 were unable to complete the test. In other words, people in this age group were more than 11 times more likely to fail the test than people 20 years younger.

During an average follow-up period of 7 years , 123 (7%) people died: cancer (32%); cardiovascular disease (30%); respiratory disease (9%); and complications of COVID-19 (7%).

There were no clear temporal trends in deaths, or differences in causes, between those who were able to complete the test and those who were unable to do so.

But the proportion of deaths among those who failed the test was significantly higher: 17.5% versus 4.5%, reflecting an absolute difference of just under 13%.

Overall, those who failed the test were in poorer health : a higher proportion were obese and/or had heart disease, high blood pressure and unhealthy blood fat profiles. And type 2 diabetes was 3 times more common in this group: 38% vs. about 13%.

After taking into account age, sex, and underlying conditions, the inability to stand unsupported on one leg for 10 seconds was associated with an 84% elevated risk of death from any cause in the next decade.

This is an observational study and as such cannot establish cause. Since the participants were all white Brazilians, the findings may not be more applicable to other ethnicities and nations, the researchers warn.

And information about potentially influential factors, including recent history of falls, physical activity levels, diet, smoking, and use of medications that can interfere with balance, was not available.

However, the researchers conclude that the 10-second balance test “provides rapid and objective feedback to the patient and healthcare professionals regarding static balance,” and that the test “adds useful information about the risk of mortality in middle-aged and older men and women.”