Summary Background A high BMI has been associated with a reduced immune response to influenza vaccination. We aimed to investigate the association between BMI and COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, vaccine effectiveness, and the risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes after vaccination by using a large representative population-based cohort. from England. Methods In this population-based cohort study, we used the QResearch database of general practice records and included patients aged 18 years or older who were registered with a practice that was part of the database in England between 8 December 2020 (date of first vaccination) in the UK), to 17 November 2021, with BMI data available. Acceptance was calculated as the proportion of people with zero, one, two , or three doses of the vaccine across all BMI categories. Efficacy was assessed through a nested matched case-control design to estimate odds ratios (ORs) for severe COVID-19 outcomes (i.e., hospital admission or death) in people who had been vaccinated versus to those not, taking into account the vaccine dose and time periods since vaccination. Multivariable Cox proportional hazard models estimated the risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes associated with BMI (baseline BMI 23 kg/m2) after vaccination. Results Among 9,171,524 participants (mean age 52 [SD 19] years; BMI 26.7 [5.6] kg/m2), 566,461 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 during follow-up, of whom 32,808 were admitted to hospital and 14,389 died. Of the total study sample, 19.2% (1,758,689) were not vaccinated, 3.1% (287,246) had one dose of vaccine, 52.6% (4,828. 327) had two doses and 25.0% (2,297,262) had three doses. In people aged 40 years and older, uptake of two or three doses of the vaccine was greater than 80% among overweight or obese people, which was slightly lower in underweight people (70–83%). Although significant heterogeneity was found between BMI groups, protection against severe COVID-19 disease (comparing people who were vaccinated versus those who were not) was high after 14 days or more from the second dose for hospital admission (underweight: OR 0·51 [95% CI 0·41–0·63]; healthy weight: 0·34 [0·32–0·36]; overweight: 0·32 [0·30 –0·34] and obesity: 0·32 [ 0.30–0.34]) and death (underweight: 0.60 [0.36–0.98]; healthy weight: 0.39 [0.33 –0.47]; overweight: 0.30 [0·25–0·35] and obesity: 0·26 [0·22–0·30]). In the vaccinated cohort, there were significant linear associations between BMI and COVID-19 hospitalization and death after the first dose, and J-shaped associations after the second dose. Interpretation Using BMI categories, there is evidence of protection against severe COVID-19 in overweight or obese people who have been vaccinated, which was of a similar magnitude to that of healthy weight people . Vaccine effectiveness was slightly lower in underweight people , in whom vaccine acceptance was also the lowest for all ages. In the vaccinated cohort, there were higher risks of severe COVID-19 outcomes for people who were underweight or obese compared to the vaccinated population with a healthy weight. These results suggest the need for specific efforts to increase uptake in people with low BMI (<18.5 kg/m2), in whom uptake is lower and vaccine effectiveness appears to be reduced. Strategies to achieve and maintain a healthy weight should be prioritized at the population level, which could help reduce the burden of COVID-19 disease. |

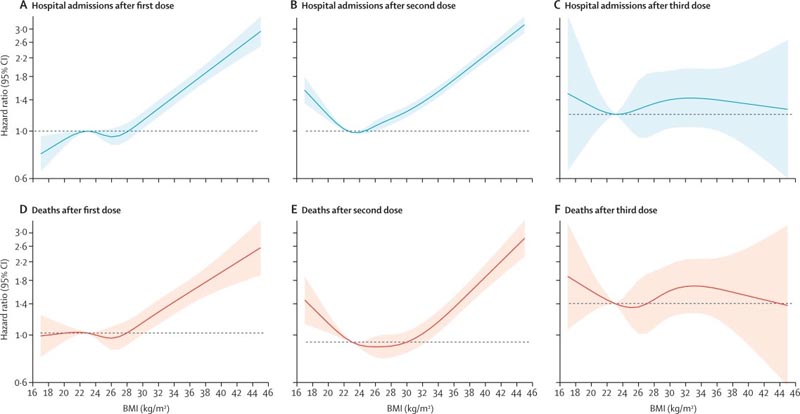

Risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes after vaccination Risk estimates 14 days after each vaccine dose. Adjusted for age, calendar week, sex, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, region, smoking, hypertension, type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and nursing home status. COVID-19 hospital admissions after first dose (A), second dose (B), and third dose (C), and COVID-19 deaths after first dose (D), second dose (E), and third dose (F).

Comments

The largest study on body mass index (BMI) and COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness suggests that two doses are highly effective against serious disease in people who are underweight, overweight or obese.

However, within the vaccinated group, those with a high or low BMI had a higher risk of hospitalization and death compared to vaccinated people of a healthy weight. The findings also suggest that underweight people were less likely to be vaccinated.

Policymakers should continue to emphasize the importance of vaccination for people of all BMI groups, the authors say.

According to a new study published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology , COVID-19 vaccines greatly reduced the number of cases of severe COVID-19 illness for everyone, regardless of their body size. The vaccine’s effectiveness was similar for those with a higher BMI and healthy weight, but slightly lower in the underweight group, who were also less likely to have been vaccinated.

In an additional analysis of vaccinated people only, among the few recorded COVID-19 cases, people with very low and very high BMI were more likely to experience severe illness than vaccinated people with a healthy weight. This replicates findings seen in a previous analysis before the vaccination program began.

Obesity was identified as a risk factor for severe COVID-19 at the start of the pandemic, which was reflected in the UK vaccine rollout in 2021 , which prioritized people with a BMI over 40 as high risk group. However, little was known until now about the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines for people with obesity. Previous work has shown that people with obesity are less likely to be vaccinated against seasonal flu and have modestly reduced benefits from flu vaccines, although the reasons for this are not well understood.

“Our findings provide more evidence that COVID-19 vaccines save lives for people of all sizes. Our results provide reassurance to people with obesity that COVID-19 vaccines are as effective for them as for people with lower BMI, and that vaccination substantially reduces the risk of severe disease if they are infected with COVID-19. 19. “These data also highlight the need for targeted efforts to increase vaccine uptake in people with low BMI, where uptake is currently lower than for people with higher BMI,” says lead author Dr. Carmen Piernas. , from the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, UK.

The researchers searched anonymised health records for more than 12 million patients across 1,738 GP practices in England participating in QResearch , a secure database of healthcare information available to verified researchers. Of these, 9,171,524 patients over 18 years of age, with BMI data, who had not previously been infected by SARS-CoV-2 were included in the study.

People were grouped according to their BMI according to four World Health Organization definitions of 18.5-24.9 kg/m2 for a healthy weight; below 18.5 for underweight; 25-29.9 for overweight; and 30 and over as obesity with levels adjusted for Asian people to reflect the greater health risks at lower BMI levels in this group. Characteristics such as age, sex, smoking and social deprivation were also taken into account in the analyses.

Of more than 9 million people included in the study, 566,461 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 during the study from December 8, 2020 (date of the first vaccine administered in the United Kingdom) to November 17, 2020. 2021. Of them, 32,808 were hospitalized and 14,389 died.

At the end of the study period, 23.3% of the healthy weight group (817,741 of 3,509,231 people), 32.6% of the low weight group (104,488 of 320,737 people), 16.8% of the overweight (513,570 of 3,062,925 people) and 14.2% of the obese group (322,890 of 2,278,649 people) had not received any dose of any vaccine against COVID-19.

To understand the vaccine’s effectiveness , researchers compared the risk of severe disease in vaccinated versus unvaccinated people at least 14 days after a second dose. They found that being vaccinated offered high protection in all BMI groups, but that the effect was slightly less in underweight people. Vaccinated people who were underweight were about half as likely to be hospitalized or die compared to unvaccinated people with the same BMI.

By comparison, people in the healthy and high BMI groups who were vaccinated were about 70% less likely to be hospitalized than unvaccinated people. People with a healthy or higher BMI were also about two-thirds less likely to die than their unvaccinated counterparts two weeks after a second dose.

Looking at data from vaccinated people only (among whom the number of COVID-19 cases dropped significantly), the researchers found that after two doses of the vaccine there was a significantly increased risk of severe disease with low BMI and high compared to a healthy BMI. For example, a BMI of 17 was associated with a 50% increased risk of hospitalization compared to a healthy BMI of 23, and a very high BMI of 44 had three times the risk of hospitalization compared to a healthy BMI.

The cause of the increased risk among people with obesity is unknown. It is consistent with the higher rate of seasonal flu infections in people with higher BMI. The authors speculate that their findings may be explained, in part, by an altered immune response in heavier individuals. The reduced effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines among people with low BMI may also reflect a reduced immune response as a consequence of frailty or other conditions associated with low body weight. More research is needed to explore the relationship between BMI and immune responses.

The authors acknowledge several limitations of the study, in particular that some BMI measurements were based on self-report or data recorded in GP records before the start of the study that may be outdated. Additionally, the limited number of people who had received three doses at the close of the study meant that the effects of the booster vaccines could not be investigated, and the data did not allow researchers to investigate between the Pfizer, AstraZeneca or Moderna vaccines, nor the variants of the virus.

Writing in a linked comment, Professor Annelies Wilder-Smith and Professor Annika Frahsa from the Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine at the University of Bern, Switzerland (who were not involved in the study) note: "There was greater acceptance of the vaccine by In contrast, underweight people were less likely to be vaccinated, which may be an unintended result of public messages that overweight people are at higher risk of severe COVID-19, further corroborated by the UK’s risk-based strategy for the vaccine rollout. These findings should drive a shift towards more targeted and differentiated public health messages to also address people who may perceive themselves to be underweight. as lower risk to improve vaccine acceptance in this group.”

Implications of all available evidence Two doses of COVID-19 vaccines provide a high level of protection against severe COVID-19 outcomes compared to no vaccination across all BMI groups. However, even after vaccination, there were significantly higher risks of severe COVID-19 in people with lower and higher BMIs compared to healthy BMIs. Future research should examine whether these associations persist after booster doses. These results suggest the need for targeted efforts to increase uptake in people with low BMI, in whom uptake is lower and vaccine effectiveness appears to be reduced. Strategies to achieve and maintain a healthy weight should be prioritized at the population level, which could help reduce the disease burden of COVID-19. |