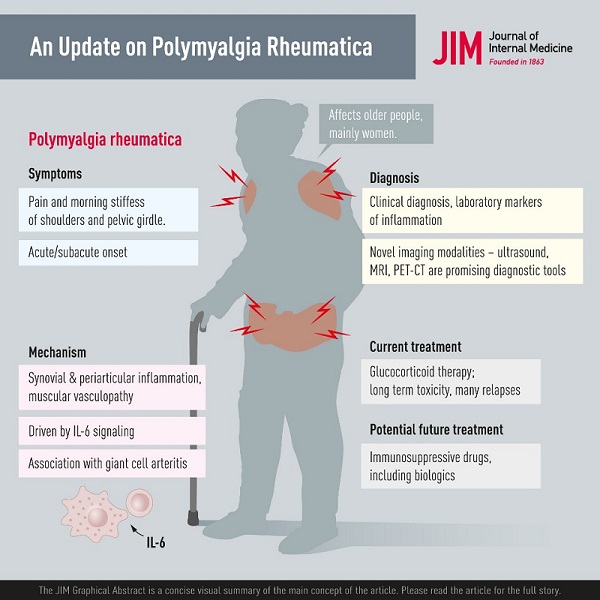

Summary Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) is the most common inflammatory rheumatic disease affecting people over 50 years of age and is 2 to 3 times more common in women. The most common symptoms are morning pain and stiffness in the shoulder and pelvic girdle and the onset may be acute or develop over a few days or weeks. General symptoms such as fatigue, fever, and weight loss may occur, probably caused by systemic IL-6 signaling. Pathology includes synovial and periarticular inflammation and muscular vasculopathy. A new observation is that PMR may appear as a side effect of cancer treatment with checkpoint inhibitors. The diagnosis of PMR is primarily based on symptoms and signs combined with laboratory markers of inflammation. Imaging modalities, including ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, and positron emission tomography, show promise in the investigation of suspected PMR. However, they are still limited by availability, high cost, and unclear performance in diagnostic work. Glucocorticoid (GC) therapy is effective in PMR and most patients respond rapidly to 15 to 25 mg of prednisolone per day. There are challenges in managing patients with PMR, as relapses occur and patients with PMR may need to remain on GC for prolonged periods. This is associated with high rates of GC-related comorbidities, such as diabetes and osteoporosis, and there are limited data on the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologics as GC-sparing agents. Finally, PMR is associated with giant cell arteritis, which can complicate the course of the disease and require more intense and prolonged treatment. |

| Epidemiology |

Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) is a rheumatic disorder associated with musculoskeletal pain and stiffness in the neck, shoulder, and hip area. The etiology is not fully understood, but there are associated environmental and genetic factors.

The incidence of PMR increases with age and is rarely seen in people under 50 years of age. Women are approximately 2 to 3 times more likely to be affected.

PMR is 2 to 3 times more common than giant cell arteritis (GCA) and occurs in approximately 50% of GCA patients. The PMR can precede, accompany or follow the ACG.

The incidence is highest in Scandinavian countries and people of northern European ancestry. The estimated incidence and prevalence of PMR are considerably lower in other parts of the world, although all racial and ethnic groups can be affected.

Several potential causes of PMR are being investigated. Some of the theories involve the HLA-DR4 genetic variant. HLA-DR4 subtypes have been associated with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and such alleles are also present in many cases where PMR and GCA occur together. The sudden onset of PMR and the nature of the symptoms such as joint pain, fever, and malaise are suspected to be the result of infections caused by viruses.

Damage to superficial arteries from high exposure to ultraviolet radiation from the sun is another proposed cause for the development of PMR. Some studies suggest that elastic fibers present in arteries and synovial membranes are damaged by ultraviolet rays. These damaged tissues can become infected with viruses that remain dormant for a long time and can reactivate later, causing PMR. Its sudden onset and the wide variation in incidence reported in various parts of the world suggest the contribution of one or more environmental agents, genetic factors, or both.

It has also been suggested that PMR and GCA may be triggered by seasonal influenza vaccination. Another study reported the first case of a PMR-like syndrome 7 days after vaccination. However, several studies have reported that symptoms generally resolve quickly in such cases.

| Pathogenesis and pathophysiology |

The typical symptoms of proximal muscle pain and stiffness in PMR may be explained by synovial and periarticular inflammation in the central joints. Biopsies from untreated PMR patients have demonstrated synovitis with infiltration of leukocytes (macrophages and memory T cells, and some B cells) and vascular proliferation.

Furthermore, activation of the vascular endothelium may be important for pathogenesis, as increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has been observed in synovial biopsies. This may contribute to the recruitment of inflammatory cells in these lesions. Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) has been shown to be expressed to a greater extent in the synovial membrane of patients with PMR compared to those with RA or osteoarthritis. It has been suggested that nociception related to local VIP production may contribute to the typical shoulder discomfort of PMR.

Furthermore, ultrasonographic investigations have revealed subacromial-subdeltoid bursitis and tendonitis of the long head of the biceps brachii in the majority of patients with PMR. Immunofluorescence microscopy of biopsies of this muscle has shown deposits of fibrinogen and IgA in the perifascicular area of the perimysium. Increased muscle microvascularization has been observed in untreated early PMR.

Plasma levels of IL-6, but not TNF-α, have been shown to be elevated in both GCA and PMR. The main source of this IL-6 release is CD4+ T cells. Furthermore, circulating levels of soluble IL-6 receptor have been shown to predict future relapses in patients with PMR, further underscoring the importance of IL-6 signaling in this context.

Perturbations of circulating T cell and B cell subsets have been described in PMR, but with inconsistent results. Since PMR is a disease of the elderly, these patterns may reflect the aging of the immune system. Elevated peripheral blood monocyte counts have been observed in both PMR and ACG, with a significant decrease after treatment in PMR, but not in ACG. In contrast to many other rheumatic disorders, no autoantibody has been consistently associated with PMR or GCA. Combined evidence supports an interaction between the innate and adaptive cellular immune system.

While metabolic characteristics (lower BMI, lower fasting glucose levels) that may contribute to immune regulation have been shown to be associated with the subsequent development of GCA, the relationship between such factors and the risk of PMR has yet to be resolved. has not been investigated.

| Clinical presentation and course of the disease |

A characteristic feature of PMR is a new, relatively acute onset of proximal muscle pain and stiffness in the neck, shoulders, upper arms, hips, and thighs. Patients often suffer from pronounced morning stiffness with difficulty getting into or out of bed in the morning with some spontaneous relief of symptoms later in the day. Stiffness even affects other physical activities in the morning, such as getting dressed or performing other daily activities.

Symptoms usually fully develop within a few days to a couple of weeks. Sometimes the onset is more insidious and can lead to nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue, arthralgia, loss of appetite, weight loss or fever. It is not unusual for some patients to undergo investigations for suspected malignancy before a diagnosis can be made with PMR.

Nonspecific clinical presentation and absence of specific laboratory findings or serologic features often lead to some delay in diagnosis.

PMR imposes a significant burden on the daily lives of older people. The psychological impact is significant, including anxiety related to active disease and side effects of glucocorticoid (GC) treatment.

| Association with temporal arteritis |

PMR and temporal arteritis (TA) often coexist, suggesting shared predisposing factors and shared disease mechanisms. Because the typical histopathology of TA in TA biopsies includes the presence of giant cells, the disease is often referred to as GCA.

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is a systemic vasculitis that can affect several large vessels, often, but not always, including the temporal artery.

A concomitant diagnosis of GCA should be suspected in a patient with PMR who also has new-onset headache, jaw claudication, new and unexplained visual symptoms, or severe constitutional symptoms (fever of unknown origin, weight loss, fatigue, etc.). Such symptoms may occur at first presentation with PMR or later during the course of the disease.

Subclinical arteritis can also occur in patients with PMR. In systematic studies of patients with a typical clinical phenotype of PMR, but without signs or symptoms consistent with GCA, histopathological findings of vasculitis in temporal artery biopsies were found in up to 21%, and sonographic features of TA in up to 32%. %. Recurrence of PMR symptoms is a common feature of GCA relapse.

| Diagnostic and classification criteria |

Many different diagnostic criteria have been proposed. The purpose of these criteria is to help clinicians make the diagnosis of PMR in individual patients. Most of these criteria are based on the demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics of PMR. The EULAR/ACR criteria are summarized in Table 1. The classification criteria are intended to be used in epidemiological studies and not to make a diagnosis in individual patients.

Table 1. EULAR/ACR provisional classification criteria for polymyalgia rheumatica (Modified from Dasgupta et al.)

| Criteria | Points |

Duration of morning stiffness > 45 min Hip pain or limited range of motion Absence of RF and/or Anti-CCP Absence of other joint involvement At least one shoulder with subdeltoid bursitis and/or biceps tenosynovitis and/or glenohumeral synovitis (either posterior or axillary) and at least one hip with synovitis and/or trochanteric bursitis Both shoulders with subdeltoid bursitis, biceps tenosynovitis, or glenohumeral synovitis | 2 1 2 1 0/1*

0/1* |

| Note: Score required for classification of polymyalgia rheumatica: 4 or more without ultrasound and 5 or more in the algorithm with ultrasound. Required criteria: age ≥50 years, bilateral shoulder pain, and abnormal C-reactive protein and/or erythrocyte sedimentation rate. * Without/with ultrasound. Abbreviations: Anti-CCP, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody; ACR, American College of Rheumatology; EULAR, European Alliance of Rheumatology Associations; RF, rheumatoid factor. | |

The sensitivity and specificity of the criteria vary depending on whether the PMR discriminates all conditions, including RA or conditions affecting the shoulders. Sensitivity and specificity also vary depending on whether or not ultrasound is used. A score ≥4 had a sensitivity of 68% and a specificity of 78%. When discriminating shoulder conditions in PMR, the specificity increased to 88%, while it was only 65% for discriminating RA from PMR. Using ultrasound, a score ≥5 had a sensitivity of 66% and a specificity of 81%.

| Diagnosis |

There is no gold standard for diagnosing PMR and, unlike many other rheumatic syndromes, there are no specific clinical manifestations, serology or other laboratory findings. As a result, diagnosis can be challenging.

Diagnosis In daily practice, the diagnosis of PMR is mainly based on the following combination: new-onset symptoms of morning stiffness and pain in the shoulder and pelvic girdle in a person aged 50 years or older, evidence of systemic inflammation with increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and/or CRP, no other disease that better explains the clinical presentation and finally abrupt response to GCs. In some diagnostic criteria, there are other specific requirements, such as a duration of symptoms of 2 weeks or negative tests for rheumatoid factors or antinuclear antibodies. |

The diagnosis of PMR should be considered clinically.

The typical case is an elderly woman with bilateral shoulder pain and stiffness first thing in the morning. Similar symptoms often occur in the pelvic girdle. Symptoms usually ease during the day. Systemic manifestations such as fever, fatigue, loss of appetite and weight loss may occur in approximately one third of patients.

Other inflammatory parameters may be elevated such as white blood cells or platelet counts and sometimes liver enzymes or alkaline phosphatase may be elevated as a sign of systemic inflammation. On clinical examination, tenderness to deep palpation of the muscles around the shoulders and thighs is often noted. Additionally, there is usually restricted mobility in the shoulders, without muscle atrophy or weakness. Occasional signs of synovitis may be seen in the shoulders, wrist joints, and knees. Finally, in PMR, most patients will respond rapidly and dramatically to GCs and, by some criteria, this response is necessary for diagnosis.

| Imaging studies |

Due to the nonspecific symptoms or laboratory findings of PMR, there is an unmet need for other modalities to confirm the diagnosis. Various imaging modalities have been used in PMR, including conventional radiology, scintigraphy, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasound, and positron emission tomography with CT (PET CT).

The goal of imaging studies in PMR is not only to confirm the diagnosis, but also to rule out differential diagnoses or comorbidities and, in some cases, coexistence with large vessel vasculitis.

Ultrasound is useful in PMR due to the nature of extra-articular soft tissue involvement . The most common findings are inflammation and effusion of the subacromial-subdeltoid bursa, tenosynovitis of the biceps, inflammation of the glenohumeral joint, and synovitis and trochanteritis of the hip. Ultrasound is also useful to rule out other differential diagnoses and to detect large vessel vasculitis and cranial arteritis when they are suspected of coexisting with PMR.

MRI has also been used , although its use is still limited in research. Findings include a characteristic pattern of symmetrical inflammation in the greater trochanter, acetabulum, and ischial tuberosity, reported in 64% of patients with PMR in one study. In another study, all patients with new-onset PMR had at least one site of myofascial inflammation. Advantages of MRI over ultrasound include that MRI is more specific with less interobserver variation in the assessment of vasculitis. Disadvantages include availability and cost.

PET CT has been used in oncology and in the research of inflammatory diseases. In patients with suspected PMR, the use of PET CT as a routine examination is not recommended due to limitations such as cost and availability. In addition to its role in visualizing inflammation in articular and extra-articular tissues, PET CT is extremely useful in confirming suspected large vessel vasculitis and differentiating between PMR and other conditions, such as malignant tumors or other rheumatic diseases. Its use is justified in patients who did not respond to initial treatment with GC. The lack of response could be explained by coexisting large vessel vasculitis, other underlying rheumatic diseases, or malignancy.

> Other imaging studies

Conventional radiography has been used previously in this context, especially in patients with suspected PMR and peripheral joint disease. Arthritis in PMR is usually not erosive, which distinguishes it from the destructive arthritis typical of RA or other arthritic diseases such as chondrocalcinosis. Scintigraphy is not currently used.

| Laboratory findings |

There are no serological or other specific laboratory findings that can confirm the diagnosis of PMR with absolute certainty.

The most frequent and important finding is the elevation of inflammatory parameters such as ESR or CRP. However, a normal ESR does not exclude the diagnosis of PMR. Other findings include normocytic normochromic anemia, thrombocytosis, and leukocytosis.

| Differential diagnosis |

Conditions affecting people in the age group of 50 years or older and that are associated with bilateral shoulder pain should be included in the differential diagnoses of PMR. The differential diagnosis should include both rheumatic and non-rheumatic diseases.

> Rheumatoid arthritis

Among the most important rheumatic conditions in the differential diagnosis of PMR is seronegative RA. This is especially true early in RA disease, which may have a prodromal phase of bilateral arthritis of the shoulder joint. Additionally, both RA and PMR can present with arthritis in the wrist joints, and if patients test negative for rheumatoid factor and/or anticyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP), differentiating between these two conditions it may not be easy.

However, the presence of symmetric arthritis of small joints should favor the diagnosis of RA. Both RA and PMR can be successfully treated with prednisolone, which limits the usefulness of this medication in differentiation. Typical extra-articular manifestations (e.g., rheumatoid nodules, cutaneous vasculitis, serositis, etc.) and positive RF/anti-CCP favor the diagnosis of RA rather than PMR.

> Myositis

Polymyositis (PM ) is another disease that can be misdiagnosed as PMR and vice versa. Both conditions affect the proximal muscle groups in the upper and lower extremities. However, the presence of muscle weakness rather than stiffness and pain is an important differential feature of PM. Furthermore, PM is generally associated with elevated serum levels of muscle enzymes, which is not a feature of PMR. Other characteristics that favor the possibility of PM are the presence of myositis-specific autoantibodies and extramuscular manifestations. Difficulty swallowing will favor the diagnosis of PM. Pure muscle weakness is not typical of PMR.

> Pain syndromes

Differentiating between PMR and pain syndromes such as fibromyalgia should be easier compared to other differential diagnoses. Fibromyalgia generally has its onset in younger age groups. Furthermore, there is no elevation of laboratory parameters indicating an inflammatory condition. It is important to differentiate between these two conditions to avoid unnecessary use of GC in patients with fibromyalgia and pain syndromes.

> Malignancy

An important differential diagnosis in PMR is malignant diseases.

PMR manifestations could represent a paraneoplastic symptom. Patients with PMR who do not respond to a daily prednisolone dose of 15 to 25 mg or who have a rapid recurrence of symptoms directly after tapering of GCs should alert the treating physician to the possibility of an underlying malignancy.

Remitting seronegative symmetric synovitis with pitting edema is a clinical syndrome characterized by the development of symmetric small joint arthritis with edema of the hands and feet, typically in rheumatoid factor-negative elderly men. This condition usually responds well to a short course of oral GC and should be one of the important differential diagnoses for PMR. A similar phenotype can be seen in paraneoplastic syndromes.

> Others

Non-inflammatory degenerative diseases, such as cervical spondylosis and osteoarthritis of the hip joint, can mimic the presentation of PMR with symptoms such as pain and morning stiffness. Radiological confirmation of osteoarthrosis (OA) or spondylosis together with the absence of active inflammatory parameters will favor the diagnosis of spondylosis and OA instead of PMR. Hypothyroidism is a common disease in women with diffuse pain, fatigue, and a fibromyalgia-like syndrome.

| PMR as an event related to the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer treatment |

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are increasingly used in cancer therapy to enhance the antitumor immune response. Treatment with monoclonal antibodies that block the CTLA-4 protein, the receptor (PD-1) or its ligand PD-L1, has been associated with the development of a number of autoimmune diseases. PMR is one of the rheumatic disorders that has been reported as a related event in this context.

Furthermore, there are several reports of cases with ’PMR-like disease’, with some atypical features, after treatment with ICIs. Careful characterization of such cases could guide us in understanding the role of the adaptive immune system in the pathophysiology of PMR.

| Treatment |

> Oral GC

The cornerstone in the treatment of PMR is oral GC. All PMR symptoms generally respond quickly to GCs. The recommended daily starting dose of prednisolone in PMR is 12.5 to 25 mg according to the most recent ACR/EULAR recommendation. An initial dose of 20 mg is superior to 10 mg but at the cost of more adverse events. Choosing within the range of 12.5 to 25 mg should consider inflammatory activity, risk of relapse, and risk of GC toxicity due to comorbidities such as diabetes or cardiovascular disease.

The prednisolone dose should be gradually reduced by about 2.5 mg per month to 10 mg per day, after which the slower taper continues. A poor response to treatment should lead to reconsidering possible differential diagnoses. GC treatment should be accompanied by supportive measures to minimize long-term toxicity such as osteoporosis.

In general, the prognosis of PMR is good and the disease usually cures within a couple of years, during which GC should be taken to control the disease and its symptoms. Some patients have a more complicated course with residual inflammation during treatment and recurrence of symptoms when attempting to reduce the GC dose. In a study by Healey, only 30% of patients were able to stop GC treatment and remain asymptomatic within 2 years of follow-up, while only 2% were able to stop GC completely within 6 months.

> injectable GC

Intramuscular methylprednisolone (IMPM) has been compared with oral GCs in the treatment of PMR in terms of efficacy and safety. In a study by Dasgupta et al., the remission rate after a 12-week double-blind phase was similar, but the mean cumulative GC dose in the intramuscular methylprednisolone group after 96 weeks was 56% of that in the intramuscular methylprednisolone group. oral GC group. The IM group had fewer long-term unwanted events. MPim is probably a suitable alternative to oral GCs in elderly patients on multiple medications, as well as in patients who experience a problem following the oral GC taper schedule and in patients with adherence problems.

> Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biological products

Due to the toxicity of long-term GC therapy, there is a clear need for alternative strategies in patients with PMR. However, antirheumatic drugs that have had great success in the treatment of RA and several other rheumatic disorders have not been extensively studied in PMR.

There is some evidence of benefit from methotrexate (MTX) in patients with PMR. In a double-blind randomized controlled trial (RCT), a lower risk of relapse and a higher likelihood of GC discontinuation were demonstrated in patients with new-onset PMR taking MTX in addition to a regular GC regimen compared to the comparison group. who was taking GC + placebo. The efficacy of MTX in recurrent and long-standing PMR has not been systematically evaluated.

Based on this type of evidence, the ACR/EULAR panel conditionally recommended considering early introduction of MTX, particularly for patients at high risk of relapse and/or prolonged therapy, for example, female patients with high baseline ESR (>40 mm /h), peripheral arthritis and/or comorbidities that may be exacerbated by GC therapy.

Data on the use of azathioprine in the treatment of PMR are very limited. Despite limited evidence, azathioprine has been used in some patients with refractory PMR. The ACR/EULAR recommendations for the treatment of PMR do not include azathioprine. A low-quality retrospective study indicated that the antimalarial agent hydroxychloroquine, which is used for other conditions, is not effective in preventing relapses in PMR.

Since the anti-IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibody tocilizumab has been shown to be effective for GCA, there is a rationale for investigating it as a therapy for PMR. Many case reports and case series suggest the efficacy of intravenous tocilizumab in individual patients with PMR. A retrospective cohort study of tocilizumab or MTX treatment for relapsed PMR in Japan indicated a significant effect of tocilizumab on GC preservation, but not MTX. Placebo-controlled RCTs of the TNF inhibitors infliximab or etanercept have not shown any significant benefit in patients with PMR and are therefore not recommended for the treatment of PMR.

> Supportive therapies

Long-term use of GC is an important factor contributing to several comorbidities in patients with rheumatic diseases, such as systemic vasculitis, PMR, and GCA. It is recommended that all patients with PMR receive other supportive therapies early in their disease, such as calcium/vitamin D and bisphosphonates to prevent osteoporosis.

| Comorbidities |

There is limited information on comorbidities in patients with PMR from large epidemiological studies. In a systematic review of the literature, there were some indications of increased risk of comorbidities in patients diagnosed with PMR. These comorbidities can be grouped into vascular disease, cancer and other diseases, the latter including hypothyroidism and diverticular disease.

The most common comorbidity reported after diagnosis of PMR is vascular disease. Vascular conditions include stroke, myocardial infarction, and peripheral vascular disease. This is in line with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease in other chronic inflammatory diseases such as RA.

While some studies reported an increased risk of cancer, others reported a lower risk or the results were equivocal. Regarding other comorbidities, there are conflicting data on an association with hypothyroidism. There are some reports of an increased risk of depression, which may be associated with chronic pain or GC treatment.

Data from a recent UK national cohort study support the increased risk of vascular disease after PMR diagnosis. In addition, there was also a risk of respiratory, kidney and autoimmune diseases after the diagnosis of PMR. At least for the last two, the explanation could be surveillance bias.

Patients with PMR have a high rate of comorbidities associated with GC treatment, such as osteoporosis, vertebral fractures, infections, cataracts, and glaucoma. However, in a cohort study in Olmstead, Minnesota, USA, only cataracts were more common in patients with PMR followed for a median of 5.8 years compared to age- and sex-matched comparators without PMR.

Possibly, the no increased risk of osteoporosis and fractures could reflect the common use of osteoporosis prophylaxis in this group of patients with planned long-term treatment with GC and with other risk factors for osteoporosis. Such patterns may depend on access to care in different populations.

| Mortality |

Given the high burden of comorbidity among patients with PMR, it is important to determine whether a diagnosis of PMR is associated with an increased risk of mortality. A recent systematic review found that patients with PMR had a higher burden of comorbid disease compared to age- and sex-matched controls. However, three previous studies reported reduced mortality among patients diagnosed with PMR.

One possible explanation for this could be surveillance bias. Patients with chronic diseases (and especially PMR where regular assessment, monitoring and monitoring are recommended) are more likely to be under active monitoring of their condition and any developing morbidity leading to management of the disease at an early stage.

Yet another study, known to be the largest study to estimate the effect a PMR diagnosis has on life expectancy, showed that a PMR diagnosis has no significant impact on life expectancy. Therefore, a diagnosis of PMR does not appear to increase the risk of premature death.

Conclusion

|