Clinical case On a summer morning in the emergency department (ED), you evaluate a patient with a chief complaint of "headache . " The patient is a 33-year-old woman who presents with several days of positional headache. The headache started while she was out playing golf. She states that the current headache episode is different from her typical headaches. Her pain worsens when she sits or stands and disappears completely when she is lying down. Screening systems are positive for nausea but negative for weakness, vision changes, numbness, tingling, or other neurological symptoms. The patient denies recent trauma. Her focused physical examination is indicated below:

Neurological: without focusing deficit, equal force/sensation at all times, self-ambulatory without ataxia. You consider a broad differential diagnosis for your headache, including tension and migraine headache, space-occupying mass, cavernous sinus thrombosis, carbon monoxide poisoning, infection, and post-procedure (lumbar puncture) headache. What else should we consider in a patient with an atypical headache, which is now positional in nature? |

Background and etiology

Spontaneous intracranial hypotension ( SIH) is a clinical condition defined by postural headaches attributed to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks or low CSF volumes. Historically, SIH has been attributed to a drop in CSF pressure that can occur as a result of trauma, surgery, CSF leak, and overdrained CSF shunt.

Headaches are a result of low CSF volume. Classically described as a pressure-like sensation, the pain is caused by the sinking of the brain away from the meninges and its resulting pulling on pain-sensitive fibers.

A CSF leak is the result of defects (in the form of fistulas or tears) and can be congenital or traumatic. There are several risk factors that can lead to CSF leak, including absence of dura mater around nerve root sheaths, congenital connective tissue disorders causing structural abnormalities, osteophyte protrusions, and spinal disc herniation.

Focal weakness in the dura mater most commonly occurs around the thoracic and lumbar spine. Subsequently, spinal manifestations, such as local back pain, may occur at the site of the CSF leak.

Epidemiology

SIH is often underdiagnosed and confused with other pathologies (see differential diagnoses). The incidence of SIH is around 5 in 100,000 and is more common in women , with a female to male ratio of 2:1. Both children and adults can be affected by SIH, although the peak incidence of SIH is around of 40 years.

Symptoms

Headaches can be bifrontal, occipital, or holocephalic (global) in location. The pain is usually sharp, orthostatic , and may worsen with Valsalva maneuvers (which worsen CSF leak). In addition to postural headaches, other symptoms of SIH include nausea, vomiting, vertigo, tinnitus, blurred or double vision, unsteady gait, neck stiffness, anorexia, facial numbness, and upper extremity paresthesia.

Unfortunately, these symptoms are neither sensitive nor specific in the diagnosis of SIH, and the constellation of SIH symptoms can mimic typical migraine headaches, meningitis, and psychogenic or somatoform disorders.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of headaches is extensive and the following list is neither exhaustive nor inclusive. However, the following should be considered in any patient presenting with headaches:

– Headache disorder (new daily persistent headache)

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage

– Dissection of the carotid or vertebral artery

– Cerebral venous thrombosis

– Benign intracranial hypertension

– Post-traumatic headache

– Meningitis

Assessment

As with any patient in the ED, you should always address life-threatening vital signs , assess the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulation, and perform a complete examination. Once you know the patient is stable , your efforts should focus on obtaining a detailed history and physical examination.

A high index of suspicion is necessary, as SIH is often confused with other headache etiologies. No specific laboratories are needed to diagnose SIH. However, you can and should obtain other relevant laboratory tests if you are trying to rule out other emerging causes of headaches (CSF studies for meningitis). Advanced imaging that can assist the emergency physician in the diagnosis of SIH is discussed below.

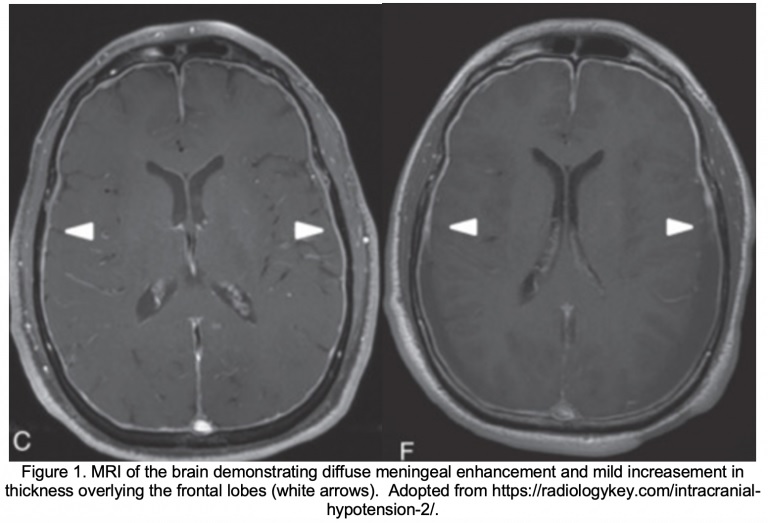

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain . The main imaging modality that would be useful in obtaining the diagnosis of SIH is an MRI of the brain with and without contrast . The acronym SEEPS, which stands for subdural fluid collections, pachymeningeal enhancement, venous engorgement, pituitary hyperemia, and cerebral flaccidity, are the main features of SIH observed on MRI.

Of these findings, the most common and pathognomonic finding is diffuse uniform pachymeningeal enhancement . In simple terms, this means enhancement of the dura mater and the outer layer of the arachnoid after administration of contrast for an MRI of the brain.

MRI of the spine . Obtaining an MRI of the spine may be helpful in identifying the source of the CSF leak. Findings on an MRI of the spine include epidural fluid leak, the presence of meningeal diverticula, fluid accumulation in the extrameningeal cavity, and shrinkage of the dural sac with concomitant distention of the epidural venous plexus.

Myelography . Iodinated contrast myelography of the entire spine (or with gadolinium followed by MRI) has been shown to be the study of choice to accurately define the location and extent of a CSF leak. Although multiple leaks are frequently found along the spine, most CSF leaks are found at the cervicothoracic junction or along the thoracic spine.

Computed tomography (CT) of the skull without contrast . Although not as definitive as MRI, CT may suggest the diagnosis by showing subdural fluid collections or obliteration of the subarachnoid cisterns and ventricular collapse. If you cannot arrange to obtain an MRI in the ED setting, CT is a reasonable first imaging option despite lower sensitivity and specificity to rule out malignant and emergent headache etiologies and identify secondary findings associated with SIH.

Image Considerations . Although MRI of the brain and spine are diagnostic for SIH, they are often difficult to obtain in the ED setting due to resource and time allocation. Alternative solutions for diagnosis include admission to an observation unit (if available) or to hospital for urgent MRI if clinical suspicion is high and the patient cannot tolerate conservative treatment (discussed below).

If the patient can tolerate conservative treatment and is considered safe for discharge, outpatient follow-up with neurology and an outpatient MRI may also be a viable option.

Treatment

Treatment of SIH usually depends on the severity of the disease. For mild cases , conservative therapy is often tried first. This includes bed rest, avoiding upright sitting, oral hydration, and pain relievers such as acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

The response to oral caffeine has been shown to be largely unpredictable, but, if attempted, a dose of 200 mg TID or 300 mg QID would be reasonable.

Regarding steroids , their use in SIH remains a controversial topic. However, there are cases where oral steroids have been successful in treating SIH. In particular, a small study demonstrated that a 2- to 4-week course of oral prednisone at 50 mg/day was successful in treating SIH in 3 patients. Subsequently, steroid therapy must be tailored to each patient,

If symptoms persist after 1 to 2 weeks of conservative management (or if the headache is associated with debilitating features), the next therapy considered is an epidural blood patch (EBP). EBPs are theorized to work by producing a tamponade effect around the site of the CSF leak, leading to short-term resolution of symptoms. Outside of the immediate post-procedure period, EBPs promote fibrin deposition and scar tissue formation around leak sites. This procedure can be repeated, if necessary.

If EBPs do not lead to symptom improvement, the next treatment options are epidural fibrin glue and surgical correction of the leaks. However, both epidural fibrin glue sealing and surgical correction of CSF leaks require identification of the points where CSF leak is occurring.

Follow-up

If the patient’s symptoms are well controlled with analgesics, antiemetics, and hydration, the patient can go home with strict return precautions with outpatient neurology follow-up.

If the patient has an intractable headache or cannot tolerate oral fluids or medications due to their symptoms, admission is warranted to consider an EBP and other advanced treatment as discussed above. This should be done in conjunction with your neurology colleagues.

Conclusion of the case

The patient underwent brain CT and CTA which showed no acute intracranial abnormalities. An MRI of the brain was subsequently obtained, which revealed diffuse pachymeningeal enhancement and thickening and engorgement of the dural venous sinus. The patient was admitted to the observation unit for further workup, including a T/L MRI of the spine, which showed a large accumulation of epidural fluid likely due to a T5-T6 nerve root sheath injury. She consulted anesthesiology, had an epidural blood patch placed, and was discharged home with resolution of her symptoms.

Points to remember

|