Summary

Across multiple disciplines performing airway management globally, preventable episodes of unrecognized esophageal intubation result in profound hypoxemia, brain injury, and death. These events occur in the hands of experienced and inexperienced practitioners. Current evidence shows that unrecognized esophageal intubation occurs frequently enough to be a major concern and merit a coordinated approach to addressing it. The harm of unrecognized esophageal intubation can be avoided by reducing the rate of esophageal intubation, combined with rapid detection and immediate action when it occurs.

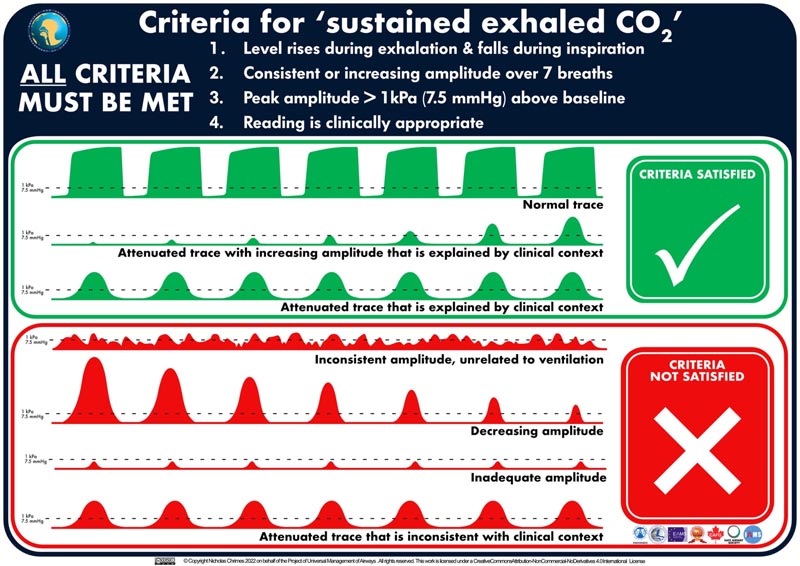

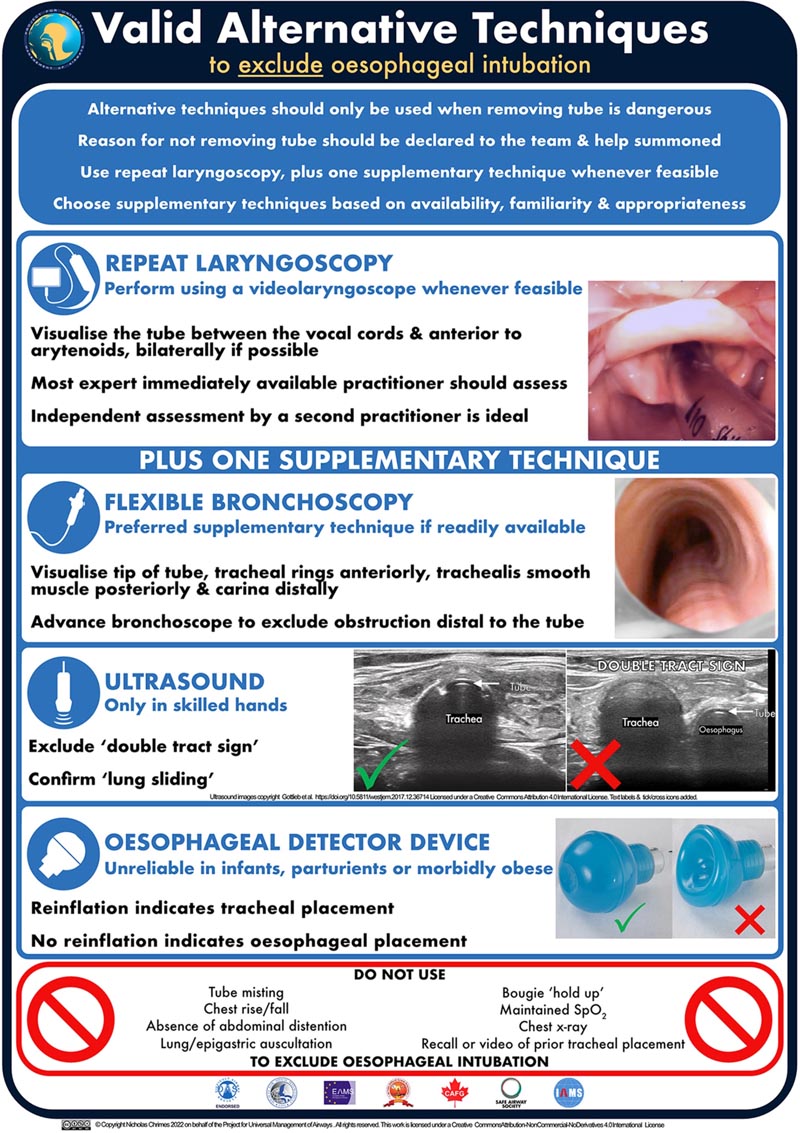

Detection of “sustained exhaled carbon dioxide” by waveform capnography is the mainstay for excluding esophageal placement of a planned tracheal tube. Tube removal should be the default response when sustained exhaled carbon dioxide cannot be detected. If default tube removal is considered dangerous, urgent exclusion of esophageal intubation using valid alternative techniques is indicated, in parallel with evaluation of other causes of inability to detect carbon dioxide.

The tube should be removed if timely restoration of sustained exhaled carbon dioxide cannot be achieved. In addition to technical interventions, strategies are required to address cognitive biases and impaired individual and team performance in stressful situations, to which all professionals are vulnerable. These guidelines provide recommendations to prevent unrecognized esophageal intubation that are relevant to all airway professionals regardless of geography, clinical location, discipline, or patient type.

Key recommendations

Esophageal placement cannot be excluded Sustained exhaled carbon dioxide cannot be restored Oxygen saturation deteriorates at any point before sustained exhaled carbon dioxide is restored

|

Background on unrecognized esophageal intubation

What is unrecognized esophageal intubation?

When patients receive general anesthesia or need help breathing in the emergency department or intensive care unit (that is, they are placed on "life support" ), they often have a breathing tube passed through the windpipe (trachea) to ensure that oxygen can reach your lungs. (“intubation”). Occasionally, this breathing tube is inadvertently introduced into the esophagus instead of the trachea, resulting in oxygen reaching the stomach instead of the lungs. If not detected quickly, this causes brain damage and death from lack of oxygen.

Why does esophageal intubation occur?

Mistakenly passing the breathing tube into the esophagus instead of the trachea can occur for a variety of reasons including misleading anatomy, technical difficulties, inexperience, or movement of the tube.

Why is esophageal intubation not always recognized?

Esophageal intubation is usually easily detected and corrected without causing any damage. In most settings (and routinely as standard of practice in any anesthesia in most high-resource countries), monitors are connected to the breathing tube that detects carbon dioxide produced only by the lungs and usually It is not present in the stomach. Therefore, carbon dioxide detection usually confirms correct placement of the breathing tube in the trachea. If no carbon dioxide is detected, this usually indicates that the breathing tube is in the esophagus. However, in some cases, carbon dioxide monitors have not been available or used, or their results have been misinterpreted. Carbon dioxide monitor misinterpretation can occur for a variety of technical reasons, but usually also contributes to the stress that arises when an emergency develops, which can affect doctors’ ability to think clearly and work in a safe manner. equipment. "Human factors" science deals with addressing these types of problems and is embedded in many industries, including aviation, but its contribution to medicine has only recently been recognized.

Emergencies such as cardiac arrest or anaphylaxis may be a reason a person is intubated. They can also be complications of intubation, even when the breathing tube is placed correctly in the trachea. These emergencies can cause abnormalities in carbon dioxide detection that resemble the situation with esophageal intubation, even when the breathing tube is in the trachea. Conversely, interruption of the oxygen supply to the patient’s blood due to esophageal intubation may be the cause of cardiac arrest. Therefore, abnormalities in carbon dioxide detection can be the cause or consequence of cardiac arrest. Therefore, it is common for these emergencies to coexist with esophageal intubation, and when this occurs, it may lead physicians to attribute the lack of carbon dioxide to cardiac arrest or anaphylaxis rather than esophageal intubation. However, although cardiac arrest can produce a very low level of carbon dioxide, it usually should not result in the detection of carbon dioxide at all . This is something that most anesthetists and other doctors who perform intubations were largely unaware of until a few years ago.

In response to several deaths from unrecognized oesophageal intubation to which this knowledge deficit contributed, the Royal College of Anesthetists implemented an educational program in 2017 "No trace = wrong place" to address it. This educational program has improved things significantly, but there are still gaps in knowledge about the impact of cardiac arrest on the ability to detect carbon dioxide among many respiratory physicians. Emergency management also creates a distraction and causes stress that may prevent the team from recognizing that the tube was mistakenly placed in the esophagus. Also rarely, in some specific circumstances, carbon dioxide may be present in the stomach and be detected for a short time even though the tube is in the esophagus.

How common is unrecognized esophageal intubation?

Esophageal intubation is relatively common . All airway management physicians would have mistakenly intubated the esophagus on multiple occasions during their career. This is usually identified quickly however and does not result in harm. Unrecognized esophageal intubation is extremely rare but almost always fatal, often resulting in death in otherwise well patients. Since reporting of these events is not mandatory, it is difficult to determine the exact incidence. In a major survey in the United Kingdom, nine unrecognized esophageal intubations were reported in a single year. Therefore, while the risk of unrecognized esophageal intubation is low, the large number of intubations performed worldwide each year means that it is responsible for a significant number of deaths, despite this low incidence.

Why are these guidelines important?

These guidelines are the first to address the issue of unrecognized esophageal placement. They also represent the first time that an airway management guideline has achieved global consensus among the world’s airway management societies. This has been achieved as part of the Universal Airway Management Project , an initiative that seeks to establish a consistent approach to airway emergencies like these across all specialties and in all parts of the world. These guidelines provide strategies and recommend equipment to help prevent esophageal intubation and promote its prompt recognition when it occurs. This includes providing techniques to help clinicians distinguish between esophageal intubations and other emergencies that could to some extent mimic their effect on carbon dioxide sensing ability.

Criteria for “sustained exhaled carbon dioxide”. This chart has been designed to be used as a basic tool to be reviewed prior to clinical use and an implementation tool to be referenced in real time during clinical practice. A high-resolution version of this graphic is available for download at https://www.UniversalAirway.org/downloads. It is recommended to print and laminate it in A3 size.

Valid alternative techniques to exclude esophageal intubation. This chart has been designed to be used as a baseline tool to review prior to clinical use and an implementation tool to be used as a real-time prompt during clinical practice [93]. A high-resolution version of this graphic is available for download at https://www.UniversalAirway.org/downloads. It is recommended to print and laminate it in A3 size . (Photos of glottis and trachea are clinical images of cadavers from the Dalhousie University Human Body Donation Program. Used with permission. Ultrasound images are copyright Gottlieb et al. https://doi.org/ 10.5811/westjem.2017.12.36714 [111] and licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Text labels and tick/cross icons have been added for this guide.)

Comments

Esophageal intubation describes the unintentional insertion of a breathing tube into the esophagus (the tube that goes to the stomach) instead of the trachea. If this is not recognized quickly, it causes brain damage or death. There have been some high profile cases of unrecognized esophageal intubation recently and these cases often result in the death of patients who are otherwise well and undergoing routine procedures (see links below).

The new guideline published by Anesthesia (a journal of the Association of Anesthetists) provides the first consensus guideline on this topic, designed to reduce preventable deaths and injuries. The authors are an international team including Dr Nicholas Chrimes, Consultant, Department of Anesthesia, Monash Medical Centre, Melbourne, Australia and Professor Tim Cook, Consultant in Anesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine, Royal United Hospitals Bath NHS Foundation Trust, Bath, United Kingdom, and Honorary Professor, Faculty of Medicine, University of Bristol, United Kingdom.

Erroneous insertion of the breathing tube into the esophagus instead of the trachea can occur for a variety of reasons including distorted anatomy, technical difficulties, physician inexperience, or movement of the tube.

Esophageal intubation is relatively common . All airway management physicians would have mistakenly intubated the esophagus on multiple occasions during their career. This is usually identified quickly and causes no harm. Failure to recognize that esophageal intubation has occurred is extremely rare, but almost always fatal. A UK survey found it caused six deaths in a single year. However, since these events are not required to be publicly reported, it is difficult to determine the exact incidence.

Esophageal intubation is usually easily detected and corrected without causing any damage. In most settings (and routinely as standard of practice during anesthesia in most high-income countries), monitors are attached to the breathing tube that detects carbon dioxide , which is only produced by the lungs and is not present in the stomach.

Therefore, carbon dioxide detection usually confirms correct placement of the breathing tube in the trachea. If no carbon dioxide is detected, this usually indicates that the breathing tube is in the esophagus.

In cases of unrecognized esophageal intubation, the inability to detect carbon dioxide after placement of a breathing tube is often erroneously attributed to the occurrence of cardiac arrest. However, while cardiac arrest is a common consequence of oxygen deprivation resulting from esophageal intubation, when the breathing tube is properly placed in the trachea, cardiac arrest due to other causes should still result in detect some carbon dioxide. Therefore, the guidelines reemphasize previous advice that cardiac arrests should not result in the complete absence of carbon dioxide unless the breathing tube is incorrectly placed.

The new guidance also emphasizes removing the breathing tube immediately as a precaution if carbon dioxide cannot be detected, unless this is dangerous, which is rarely the case. In the unusual situation where removing the default tube is thought to put the patient at risk, clear recommendations are provided on alternative ways to exclude esophageal intubation and correct other causes of carbon dioxide absence.

It also recommends that exhaled carbon dioxide monitoring and pulse oximetry (which measures oxygen levels in the blood) be available and used for all procedures requiring a breathing tube, and that a videolaryngoscope (a intubation equipped with a video camera to improve view) is used to insert the breathing tube whenever possible to ensure correct placement. Another factor that has contributed to some of these tragic deaths is confusing other similar readings on monitors with carbon dioxide, so the guide recommends standardizing and improving the distinctiveness of how these readings are displayed on the screen.

Beyond these technical factors, the new guidance notes that the contribution to these tragic outcomes cannot be underestimated by the stress and confusion that arises, even among experienced medical teams, when such emergencies occur. The impact of such factors on crisis management has long been recognized in other safety-conscious industries, such as aviation, but is a recent and relevant addition to the understanding of adverse outcomes in medicine. The guide recommends techniques to help address this.

The authors conclude: “The continued occurrence of death and serious harm from unrecognized esophageal intubation worldwide suggests that a prevention approach focused solely on emphasizing tube removal if no carbon dioxide is detected is not a complete solution.” .

This guideline emphasizes this point but also provides a more comprehensive approach that addresses both technical and human factors-based contributions to the occurrence of unrecognized esophageal intubation. The emphasis is on the trigger for tube removal being the identification of an unacceptable risk rather than a definitive diagnosis that it is out of place.”