Background

Although the consequences of lack of sleep for obesity risk are increasingly evident, experimental evidence is limited and there are no studies on the distribution of body fat.

Goals

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of experimentally induced sleep restriction in the setting of free access to food on energy intake, energy expenditure and regional body composition.

Methods

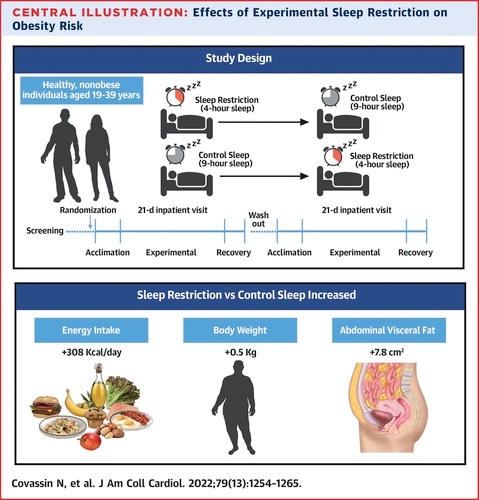

Twelve healthy, nonobese individuals (9 men, age range 19 to 39 years) completed a randomized, controlled, crossover, 21-day hospitalization study comprising 4 days of acclimatization, 14 days of experimental sleep restriction (opportunity to sleep 4 hours) or control sleep (opportunity to sleep 9 hours) and a 3-day recovery segment. Repeated measures of energy intake, energy expenditure, body weight, body composition, fat distribution, and circulating biomarkers were acquired.

Results

With sleep restriction versus control, participants consumed more calories (P = 0.015), increasing protein (P = 0.050) and fat (P = 0.046) intake. Energy expenditure remained unchanged (all P > 0.16).

Participants gained significantly more weight when exposed to experimental sleep restriction than during control sleep (P = 0.008).

While changes in total body fat did not differ between conditions (P = 0.710), total abdominal fat increased only during sleep restriction (P = 0.011), with significant increases evident in subcutaneous and visceral abdominal fat depots. (P = 0.047 and P = 0.042, respectively).

Conclusions

Sleep restriction combined with ad libitum food promotes excessive energy intake without changing energy expenditure. Weight gain and, in particular, central fat accumulation indicate that sleep loss predisposes to visceral abdominal obesity.

Comments

Findings from a randomized controlled crossover study led by Naima Covassin, Ph.D., a cardiovascular medicine researcher at Mayo Clinic, show that lack of sufficient sleep led to a 9% increase in total abdominal fat area and an increase of 11% in abdominal visceral fat area, compared to control sleep. Visceral fat is deposited deep in the abdomen around internal organs and is strongly linked to heart and metabolic diseases.

The findings are published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology , and the study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Lack of sufficient sleep is often a behavioral choice, and this choice has become increasingly widespread.

More than a third of adults in the U.S. routinely do not get enough sleep, in part due to shift work and smart devices and social media used during traditional sleep schedules. Additionally, people tend to eat more during longer waking hours without increasing physical activity.

"Our findings show that shorter sleep, even in young, healthy, and relatively thin subjects, is associated with an increase in calorie intake, a very small gain in weight, and a significant increase in fat accumulation within the belly." says Virend Somers, M.D., Ph.D., Alice Sheets Marriott Professor of Cardiovascular Medicine and principal investigator of the study.

"Normally, fat is preferentially deposited subcutaneously or under the skin. However, inadequate sleep appears to redirect fat to the most dangerous visceral compartment. Importantly, although during recovery sleep there was a decrease in fat intake of calories and weight, visceral fat continued to increase. This suggests that inadequate sleep is a previously unrecognized trigger of visceral fat accumulation and that regaining sleep, at least in the short term, does not reverse the accumulation of contributing visceral fat to epidemics of obesity, cardiovascular and metabolic diseases," says Dr. Somers.

The study cohort consisted of 12 healthy, nonobese people, each of whom spent two 21-day sessions in the inpatient setting. Participants were randomly assigned to the control group (normal sleep) or the restricted sleep group during one session and the opposite during the next session, after a three-month washout period. Each group had access to free choice of foods throughout the study. The researchers monitored and measured energy intake; Waste of energy; body weight; body composition; fat distribution, including visceral fat or fat within the belly; and circulating biomarkers of appetite.

The first four days were an acclimatization period. During this time, all participants were allowed to sleep nine hours in bed. Over the next two weeks, the sleep-restricted group was allowed four hours of sleep and the control group was kept on nine hours. This was followed by three days and nights of recovery with nine hours in bed for both groups.

Participants consumed more than 300 additional calories per day during sleep restriction, consuming approximately 13% more protein and 17% more fat, compared to the acclimatization stage. That increase in consumption was highest in the first days of sleep deprivation and then decreased to baseline levels during the recovery period. Energy expenditure remained practically the same at all times.

"Visceral fat accumulation was only detected by CT scan and would have otherwise been missed, especially since the weight gain was quite modest, only about a pound," says Dr. Covassin. "Weight measures alone would be falsely reassuring in terms of the health consequences of inadequate sleep. Also concerning are the potential effects of repeated periods of inadequate sleep in terms of progressive and cumulative increases in visceral fat over several years." ".

Dr. Somers says behavioral interventions, such as increasing exercise and making healthy food choices, should be considered for people who cannot easily avoid sleep disruption, such as shift workers. More studies are needed to determine how these findings in healthy young people relate to people at higher risk, such as those who are already obese or have metabolic syndrome or diabetes.