Summary There is strong evidence that sex chromosomes and sex hormones influence the regulation of blood pressure (BP), the distribution of cardiovascular (CV) risk factors and comorbidities differentially in women and men with essential arterial hypertension. . The risk of cardiovascular disease increases at a lower BP level in women than in men, suggesting that sex-specific thresholds for the diagnosis of hypertension may be reasonable. However, due to a paucity of data, particularly from specifically designed clinical trials, it is not yet known whether hypertension should be managed differently in women and men, including treatment goals and the choice and doses of antihypertensive medications. . Accordingly, this consensus document was intended to provide a comprehensive overview of current knowledge on sex differences in essential hypertension, including the development of BP across the lifespan, the development of hypertension, the pathophysiological mechanisms that regulate BP, the interaction of BP with CV risk factors and comorbidities, hypertension-mediated organ damage in the heart and arteries, impact on incident CV disease, and differences in the effect of antihypertensive treatment. The consensus document also highlights areas where focused research is needed to advance sex-specific prevention and treatment of hypertension. |

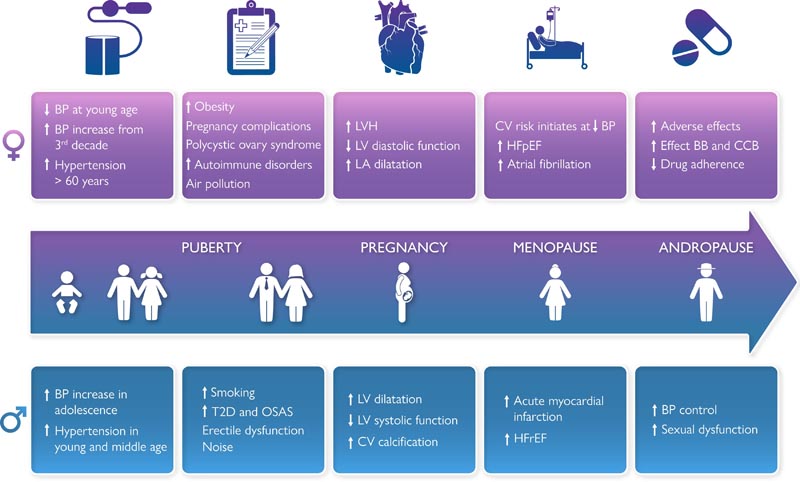

Graphic summary

Sex differences in hypertension. BP, blood pressure; CV, cardiovascular; T2D, type 2 diabetes; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; VI, left ventricle; Left atrium LA; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; BB, beta blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

High blood pressure, particularly elevated systolic blood pressure (BP), remains a major cause of reduced quality of life, cardiovascular (CV) morbidity and mortality, and all-cause mortality worldwide. Both the development and regulation of BP are influenced by the biological effects of sex chromosomes, sex hormones, and reproductive events . Furthermore, the sex difference in the prevalence of hypertension has been related to ethnicity, comorbidities, socioeconomic status, education, and environmental pollution in middle-aged and older adults. Previous publications have documented important sex differences in hypertension related to key BP regulators, comorbidities, cardiovascular complications, and adverse effects of antihypertensive drugs.

However, there is a paucity of reports of sex-specific effects from clinical trials in hypertension. Recent data indicate that the risk of CV complications begins with lower BP levels in women than in men , questioning the current practice of using the same BP threshold to identify hypertension in both sexes. The scope of this collaborative paper is to provide an overview of the current knowledge on sex differences in essential arterial hypertension, associated organ damage and CVD and the management of hypertension (Graphic Summary), as well as the identification of knowledge gaps that hinder the development of sex- and gender-based hypertension management.

1. Key messages about sex differences in the development of BP across the lifespan

- Healthy young women have lower BP than men at the same age, but experience a more pronounced increase in BP starting in the third decade of life.

- A better understanding of the underlying mechanisms of BP rise in midlife may provide targets for improving hypertension prevention in both sexes.

2. Key messages regarding sex differences in BP regulators, CV risk factors and comorbidities

Sex differences in BP regulators

Regulation of vascular function and BP differs between women and men, particularly due to sex differences related to the autonomic nervous system, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), bradykinin, nitric oxide, natriuretic peptides. brain and humoral mechanisms related to sex chromosomes, sex hormones and other hormones.

- The activity of autonomic and endocrine BP regulators differs between sexes and may influence drug efficacy and adverse effects.

- The prevalence and influence of traditional risk factors on CVD vary between women and men. Sex-specific CV risk factors are documented in both sexes. Better integration of these differences into risk assessment tools will improve CVD prevention.

3. Key messages about sex differences in hypertension-mediated organ damage

Sex-specific CV risk factors

Important sex-specific CV risk factors have been identified. In men, erectile dysfunction and androgenic alopecia are associated with an increased risk of hypertension and CVD. Women experience important changes in sex hormones throughout their lives that affect CV risk. Pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders increase the risk of chronic hypertension and CVD, even before the menopause transition. Detailed European recommendations on the management of peripartum hypertension have recently been published. Women with PCOS have an increased risk of hypertension, including hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. In transgender populations , insufficient data have been reported on the effects of gender-affirming hormone therapy on the incidence of hypertension.

Inflammatory and autoimmune disorders are associated with an increased risk of hypertension and CVD, and both the innate and adaptive immune systems are influenced by sex hormones.49 While progesterone and androgens are considered immunosuppressants, estrogens are considered immunostimulators, contributing to the observed preponderance of most autoimmune diseases in women.

- Organ damage caused by hypertension, such as hypertensive heart disease and arterial dysfunction, show sex-specific incidence, threshold values, and treatment success and may develop despite treatment.

- Identification of the underlying mechanisms for such development in women and men may provide targets to reduce high-risk phenotypes and progression to CVD.

4. Key messages about sex differences in the association of BP with CVD

Arterial structure and function

Sex differences have been documented in both microvascular and macrovascular structure and function. Sex- and age-specific threshold values for the diagnosis of arterial dysfunction in large arteries by arterial stiffness and intima-media thickness, and in small arteries by mean lumen ratio and flow-mediated vasodilation have been published. Women have smaller aortic root dimensions than men, even after adjusting for body size.95 documented in several studies. Augmentation pressure and augmentation rate are higher in women of all ages, while carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity (PWV) does not differ by sex. More pronounced increases in carotid-femoral PWV and peripheral vascular resistance are observed with aging and hypertension in women compared to men.

- Women with hypertension more frequently develop atrial fibrillation and HFpEF, while men more frequently develop AMI and HFrEF.

- CV risk increases at lower BP levels in women than in men. Future research should explore whether different diagnostic BP threshold values or treatment goals in women and men with hypertension can improve CVD prevention.

5. Key messages about sex differences in the effect of antihypertensive treatment

The association of blood pressure with CVD

The 2019 Global Burden of Disease study report confirmed that elevated systolic blood pressure was the largest risk factor for mortality in women worldwide and second only to smoking in men. Most of these deaths are caused by CVD. Hypertension in midlife appears to be more harmful in women than in men of similar age, with hypertension being a greater risk factor for myocardial infarction, cognitive decline, and dementia.

Ambulatory BP recording has documented higher BP during sleep in men in population-based studies, but a similar decrease in BP from day to night (immersion) and a prevalence of non-immersion in both sexes. Systolic BP during sleep is a stronger predictor of all-cause mortality and CVD in women than in men. In a study in the Italian district of Umbria, non-submerged hypertension was associated with an increased risk of CVD only in women.

Several studies have now documented that the risk of CVD increases at a lower level of BP in women than in men, including the risk of myocardial infarction, heart failure, and stroke. A case-control study of risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries found that hypertension was associated with a higher risk of myocardial infarction in older women than in men. Furthermore, the community-based Tromso Study found that higher BP is a stronger risk factor for myocardial infarction in women than in men.

- Sex differences in the efficacy and adverse effects of antihypertensive drugs are well described. These differences should be better communicated to healthcare providers to promote optimal antihypertensive drug treatment.

- In general, men treated for hypertension achieve better BP control than women. Future research should focus on the underlying causes of this difference, including patient-related factors, healthcare-related factors, sociodemographic factors, and medication-related factors to provide sex-specific counseling for optimization of antihypertensive drug therapy.

Conclusions

Our knowledge of sex differences in hypertension has advanced substantially in recent decades, but much of this knowledge awaits clinical adoption. Better implementation of sex differences in BP development, regulation, and CV risk factors in prevention tools is likely to improve CVD prevention, particularly in women. Better communication of known sex differences in the effectiveness and adverse effects of antihypertensive medications to healthcare providers may optimize treatment and improve patient adherence.

However, important knowledge gaps remain related to the prevention of organ damage and cardiovascular disease in hypertension. Hypertension-mediated organ damage shows sex-specific incidence, threshold value, and treatment success. Identification of the underlying mechanisms for the development of CV organ damage in women and men may provide new strategies for the prevention of high-risk phenotypes and progression to CVD. Finally, future clinical studies should explore whether the use of sex-specific BP threshold values and treatment goals in hypertension can improve CVD prevention.