Background

The first wave of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China, outside of Hubei province, was addressed with the implementation of aggressive public health measures. These measures relied heavily on mass mobility restrictions, universal fever screening in all settings, and home- and neighborhood-focused social distancing that was enforced by large teams of community workers, as well as the deployment widespread of social media applications based on artificial intelligence and the use of big data.

It has been questioned whether some or all of these measures would be acceptable and feasible in settings outside mainland China.

Hong Kong is a Special Administrative Region of China that operates with a high degree of autonomy. It is located off the mainland on China’s southern coast, neighboring Guangdong province, which has recorded the highest number of confirmed COVID-19 cases (1,490 cases as of March 31, 2020) outside of Hubei. Having been one of the worst-hit epicenters during the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in 2003, the Hong Kong community has prepared itself to respond to emerging infectious diseases.

A number of public health measures have been implemented to delay and reduce local transmission of COVID-19, and there have been important changes in population behavior.

The current initial containment or suppression measures used to control COVID-19 in Hong Kong include intense infection surveillance, not only in incoming travelers but also in the local community, with around 400 outpatients and 600 inpatients tested. each day at the beginning of March 2020.

Once people are identified as positive for COVID-19, they are isolated in the hospital until they recover and stop shedding the virus. Their close contacts are traced (from 2 days before the onset of illness) and quarantined in special facilities, including holiday camps and newly built housing estates.

Because not all infected people will be identified, containment measures only work if social distancing measures or behavioral changes also reduce so-called silent transmission in the community as a whole.

A series of public health measures have been implemented to suppress local transmission of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hong Kong. We examine the effect of these interventions and public behavioral changes on COVID-19 incidence as well as influenza virus infections , which might share some aspects of transmission dynamics with COVID-19.

Implications of all available evidence Experience in Hong Kong indicates that COVID-19 transmission can be contained with a combination of testing and case isolation, in addition to tracing and quarantining their close contacts, along with some degree of social distancing to reduce community transmission of unidentified cases. |

Methods

We analyzed data on laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases, influenza surveillance data in outpatients of all ages, and influenza hospitalizations in children.

We estimated the daily effective reproduction number (Rt) for COVID-19 and influenza A H1N1 to estimate changes in transmissibility over time.

Attitudes toward COVID-19 and changes in population behavior were reviewed through three telephone surveys conducted from January 20 to 23, February 11 to 14, and March 10 to 13, 2020.

Results

The transmissibility of COVID-19 measured by Rt has remained at approximately 1 for 8 weeks in Hong Kong.

Influenza transmission decreased substantially after the implementation of social distancing measures and changes in population behaviors in late January, with a 44% (95% CI: 34-53%) reduction in the community, from an estimated Rt of 1·28 (95% CI 1·26–1·30) before the start of school closure to 0·72 (0·70–0·74) during the weeks of closure.

Similarly, a 33% (24–43%) reduction in transmissibility was observed based on pediatric hospitalization rates, from an Rt of 1·10 (1·06–1·12) before the start of lockdown. the school to 0·73 (0·68–0·77) after school closure.

Among respondents, 74.5%, 97.5% and 98.8% reported wearing masks when going out, and 61.3%, 90.2% and 85.1% avoided crowded places in the surveys. 1 (n = 1008), 2 (n = 1000) and 3 (n = 1005), respectively.

We identified considerable increases in the use of preventive measures in response to the threat of COVID-19. In recent years, face masks have been used primarily by people in the general community who are sick and by those who feel particularly susceptible to infection and wish to protect themselves.

We found that 74.5%, 97.5% and 98.8% of respondents wore masks when going out; 61 · 3%, 90 · 2% and 85 · 1% avoided going to crowded places; and 71·1%, 92·5%, and 93·0% reported washing or sanitizing their hands more frequently.

In the surveys we asked the subset of respondents who were parents of school-age children about their support for school closures and their children’s activities during school closures. Among respondents who were parents, 249 (95·4%) of 261 and 192 (93·7%) of 205 agreed or strongly agreed that school closure was needed as a control measure for COVID-19. in Hong Kong, and 209 (80·1%) of 261 and 141 (68·8%) of 205 responded that their children had no contact with people other than members of their household on the previous day.

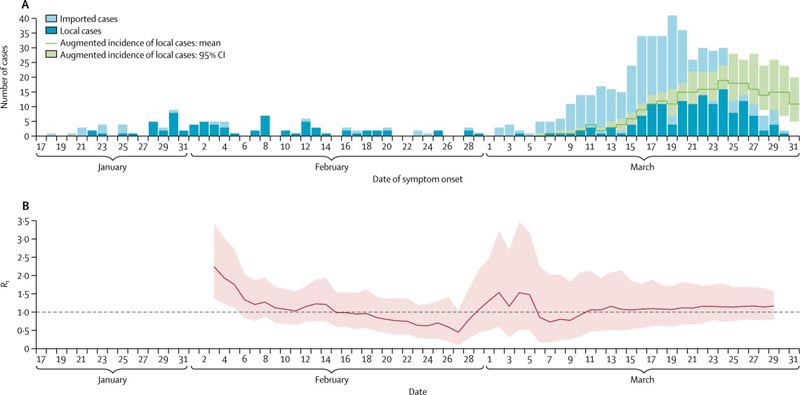

(A) Incidence of local COVID-19 cases in Hong Kong (dark blue bars) and cases infected overseas but detected locally (light blue bars). Increased incidence includes estimated additional cases that have occurred but have not yet been identified due to reporting delays. (B) Estimates of daily COVID-19 Rt over time. Pink shaded area indicates 95% CI. The dashed line indicates the critical threshold of Rt = 1. All dates are in 2020. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019. Rt = effective reproduction number.

(A) Incidence of local COVID-19 cases in Hong Kong (dark blue bars) and cases infected overseas but detected locally (light blue bars). Increased incidence includes estimated additional cases that have occurred but have not yet been identified due to reporting delays. (B) Estimates of daily COVID-19 Rt over time. Pink shaded area indicates 95% CI. The dashed line indicates the critical threshold of Rt = 1. All dates are in 2020. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019. Rt = effective reproduction number.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that the package of public health interventions (including border entry restrictions, quarantine and isolation of cases and contacts, and population behavioral changes such as social distancing and personal protective measures ) that Hong Kong has implemented since late January 2020, is associated with reduced spread of COVID-19 .

In the 10 weeks since the first known individual with COVID-19 in Hong Kong began showing symptoms, there has been little sustained local transmission of the disease.

| Our findings strongly suggest that social distancing and population behavioral changes, which have a social and economic impact that is less disruptive than total lockdown, can significantly control COVID-19. |

The rising number of imported infections in March poses a challenge to suppression efforts. This increase has occurred concurrently with the relaxation of some voluntary avoidance behaviors in the broader community. Without strengthening social distancing measures, local infections are likely to continue to occur, given that the effective reproduction number is approximately 1 or slightly above 1.

Travel measures and test, trace and treat efforts are particularly important to maintain suppression, although these measures will become increasingly difficult to implement as case numbers rise. In addition to case identification with isolation, contact tracing and quarantine, social distancing has also likely played an important role in suppressing transmission.

We found that control measures and changes in population behavior coincided with a substantial reduction in influenza transmission in early February 2020.

This observation suggests that the same measures would also have affected the transmission of COVID-19 in the community, because there will be some similarities: as well as some differences in the modes of transmission of influenza and COVID-19. The potentially higher basic reproduction number for COVID-19 indicates that it could be more difficult to control than influenza.

Because a variety of measures were used simultaneously, we were not able to separate the specific effects of each, although this may be possible in the future if some measures are strengthened or relaxed locally, or with the use of international or subnational comparisons of the application. differential of these measures.

The estimated 44% reduction in influenza transmission in the general community in February 2020 was much greater than the estimated 10-15% reduction in transmission associated with school closures alone during the 2009 pandemic, and the 16% reduction in influenza B transmission associated with school closures during winter 2017-18 in Hong Kong.

Therefore, we estimate that other social distancing measures and avoidance behaviors have had a substantial effect on influenza transmission in addition to the effect of school closures. However, if the basic reproduction number of COVID-19 in Hong Kong exceeds 2, (it was 2 2 in Wuhan),11 we would need a more than 44% reduction in COVID-19 transmission to completely avoid an epidemic. local.

However, a reduction of this magnitude could substantially flatten the peak and area under the epidemic curve, thus reducing the risk of exceeding the capacity of the health system and potentially saving many lives , especially among older adults.

The postponement of the resumption of classes in local Hong Kong schools after the Chinese New Year holiday is technically a suspension of classes rather than a school closure, because most teachers still have to go to school facilities. school to plan e-learning activities and do homework. . Complete school closures have been implemented locally in previous years, including during the SARS epidemic in 2003, during the flu pandemic in 2009, and to control seasonal influenza epidemics in 2008 and 2018.

Although school closures can have considerable effects on influenza transmission, their role in reducing COVID-19 transmission will depend on children’s susceptibility to infection and their infectiousness if infected. Both factors are the main unanswered questions today. Despite this acknowledged uncertainty, our surveys revealed considerable local support for school closures.

Individual behaviors in the Hong Kong population have changed in response to the threat of COVID-19. People have chosen to stay home, and in our most recent survey, 85% of respondents reported avoiding crowded places and 99% reported wearing face masks when leaving home. Using similar surveys, mask use during the SARS outbreak in 2003 was 79% and peaked at 10% during the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic in 2009.

These changes in behavior indicate the level of concern among the population about this particular infection and the extent of voluntary social distancing, in addition to the distancing created by school closures. However, we identified evidence of reductions in voluntary social distancing behaviors in our third survey in March, perhaps indicating some fatigue with these measures.

Our study has some limitations .

First, we were unable to identify which measure was potentially the most effective and whether border restrictions, quarantine and isolation, social distancing or behavioral changes are more important in suppressing COVID-19 transmission. Each likely plays a role.

Unlinked cases have been identified in the community and will continue to be identified, indicating that not all chains of transmission have been identified through contact tracing of known cases. Although we have observed main effects of control measures and behavioral changes on influenza transmission, the effects could be of different magnitude for COVID-19 due to differences in transmission dynamics.

Second, our surveys of population behaviors could have been affected by response bias , since we relied on self-reported data. They might also have been affected by selection bias among working adults, although this should have been reduced by conducting surveys during non-working hours and during working hours; we were unable to assess possible selection bias.

Without a baseline survey before January 23, 2020, we would not be able to compare changes in behaviors, although results from similar surveys from previous epidemics can be used for comparison.

Finally, although we identified reductions in the incidence of influenza virus infections in outpatients and pediatric patients, these time series may be affected by reduced health care-seeking behaviors and limited access to healthcare. medical care that likely resulted from the closure of a private clinic, which occurred around the Chinese New Year holiday period.

Conclusion :

Our study suggests that the measures taken to control the spread of COVID-19 have been effective and have also had a substantial impact on influenza transmission in Hong Kong.

Although the transmission dynamics and modes of transmission of COVID-19 have not been precisely elucidated, it is likely that they share at least some characteristics with influenza virus transmission, because both viruses are directly transmissible respiratory pathogens with a dynamic of similar viral clearance.

The measures implemented in Hong Kong are less drastic than those used to contain transmission in mainland China, and are likely more feasible in many other places around the world. If these measures and population responses can be sustained, avoiding fatigue among the general population, they could significantly mitigate the impact of a local COVID-19 epidemic.

Interpretation Our study shows that non-pharmaceutical interventions (including border restrictions, quarantine and isolation, distancing and changes in population behavior) were associated with reduced transmission of COVID-19 in Hong Kong, and are also likely that have substantially reduced influenza transmission by early February 2020. |