Anaphylaxis is a severe systemic hypersensitivity reaction that usually has a rapid onset and can cause death. The overall prognosis is good, with a mortality rate in the general population <1 per million per year.

The most common triggers are food, drugs, and poison. The diagnosis is admitted if there is exposure to a known trigger; however, in up to 30% of cases, there may be no obvious etiology (’idiopathic’ or ’spontaneous’ anaphylaxis).

This condition has a clinical diagnosis but no symptoms are specific. It is clinically characterized by:

• Sudden onset with rapid progression.

• Airway and/or breathing and/or circulation (ABC) problems.

• Changes in the skin and/or mucous membranes (hives, redness or angioedema).

Many patients with anaphylaxis do not receive the correct treatment because they do not recognize the condition. The aim of this article is to provide a summary of the latest updated guidance from the UK Resuscitation Council (2021).

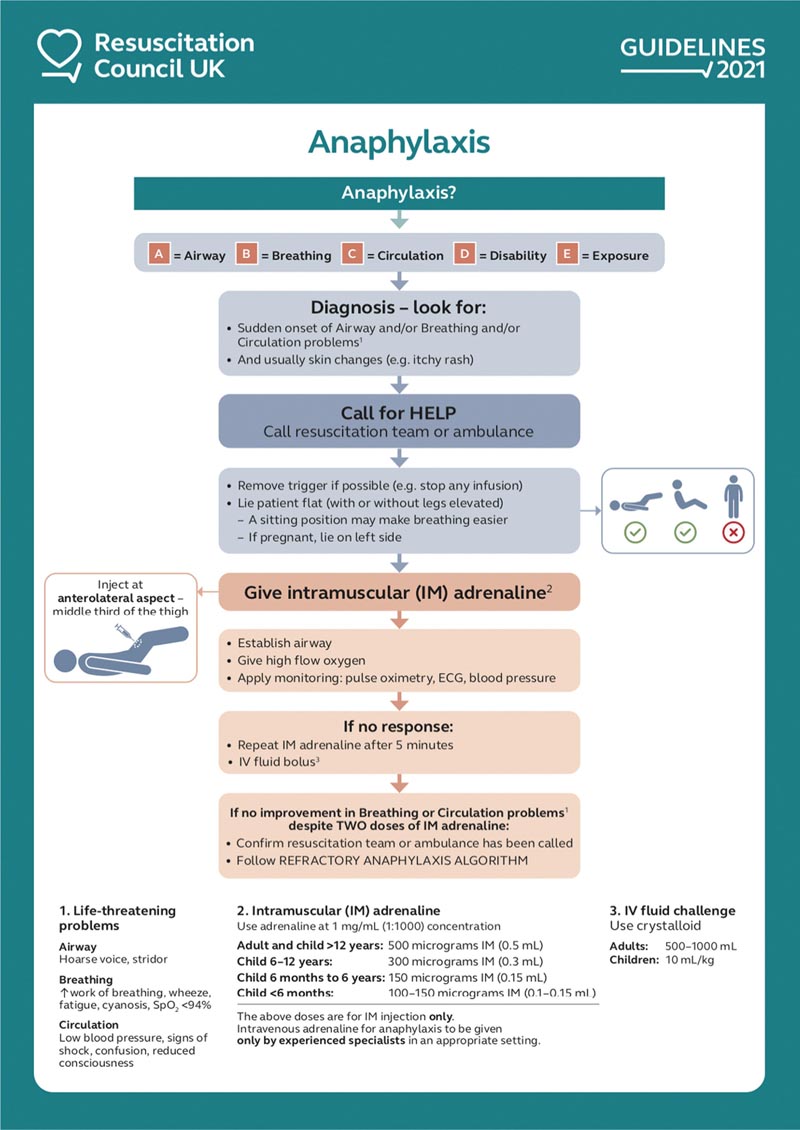

| The importance of proper positioning in the treatment of suspected anaphylaxis |

Correct posture is essential. Changes from supine to standing are associated with cardiovascular collapse and death during anaphylaxis, due to a reduction in venous return and consequent reduction in myocardial filling and perfusion. The recumbent position, with or without the legs raised, is important to maximize venous return. In cases where symptoms predominantly affect the airway or breathing, the patient may prefer to lie semi-lying, again with or without legs elevated.

| Emphasis on the use of IM adrenaline in the initial treatment of anaphylaxis |

IM epinephrine is the first-line treatment (Fig. 1) and delays in administration are associated with more severe outcomes and possibly death. Fatal anaphylaxis is rare but also very unpredictable, so all cases should be treated as life-threatening.

In approximately 10% of cases, ABC problems persist despite one dose of IM adrenaline, but most respond to a second or third dose.

Up to 5% of cases present with biphasic anaphylaxis, in which ABC features initially resolve but then reappear several hours later in the absence of further exposure to the allergen.

Fig. 1 Initial treatment of anaphylaxis. Reproduced with permission of Resuscitation Council UK. IM = intramuscular; IV = intravenous; SpO2 = oxygen saturation.

| Antihistamines are considered a third-line intervention and should not be used to treat ABC problems. |

There is no solid scientific evidence to support the use of antihistamines in the initial treatment of anaphylaxis, and they do not lead to resolution of respiratory or cardiovascular features such as adrenaline, nor do they improve survival.

The use of antihistamines is intended to treat skin symptoms (such as hives or angioedema) that may occur as part of anaphylaxis, once the ABC features have resolved. Non-sedating antihistamines (eg, cetirizine) are of choice since first-generation antihistamines (such as chlorphenamine) can cause sedation and, if administered rapidly as an intravenous bolus, can precipitate hypotension.

| Corticosteroids (e.g., hydrocortisone) are no longer recommended for routine emergency treatment of anaphylaxis |

The routine use of corticosteroids is discouraged. Its use is associated with increased morbidity even after correcting the severity of the reaction. Like antihistamines, steroids are administered much more frequently than adrenaline, raising concerns about postponing appropriate treatment since there is no evidence that they reduce severe reactions or prevent biphasic responses.

It is important to note that there are specific scenarios in which corticosteroids may be beneficial: first, anaphylaxis that occurs in the context of poorly controlled asthma; and second, in cases of refractory anaphylaxis (defined as the persistence of ABC features despite two appropriate doses of adrenaline). In these cases, the balance of risks and benefits is different and, given the uncertainty in the evidence, corticosteroids may be productive but should not delay or replace adequate doses of adrenaline when treating anaphylaxis.

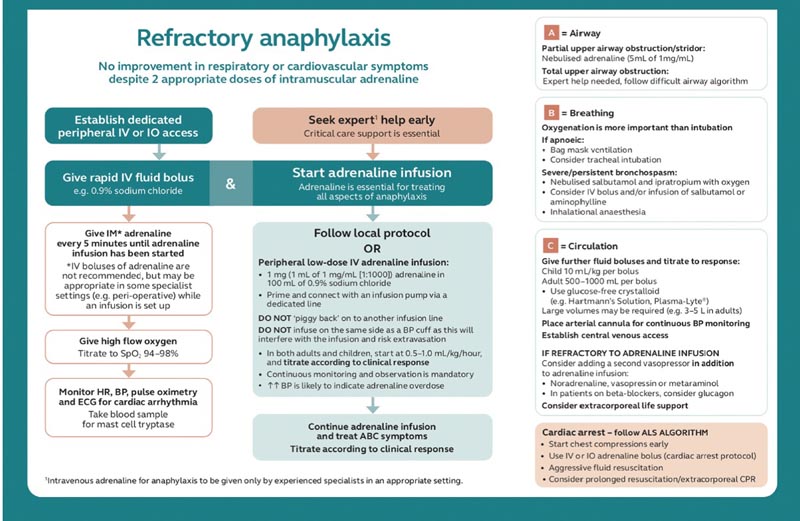

| Treatment of refractory anaphylaxis (Fig. 2) |

It is defined as anaphylaxis requiring continued treatment, due to persistent respiratory or cardiovascular symptoms, despite two doses of IM adrenaline (although most respond to three).

The pathophysiology of refractory anaphylaxis is likely due to continued release of inflammatory mediators, insufficient circulating adrenaline (usually due to suboptimal dosing, reduced circulating blood volume, or, less commonly, tachyphylaxis). Extravasation of plasma equivalent to one-third of the circulating blood volume can occur within minutes in severe reactions, and venous return may be impaired even in those without clinically evident hemodynamic compromise.

Intravenous fluid infusion is crucial to treat shock and provide sufficient circulating volume to maintain cardiac output and deliver epinephrine at the tissue level.

The risk of adverse effects due to IV epinephrine is much greater than with IM administration. Excessive doses may cause tachyarrhythmias, severe hypotension, myocardial infarction, stroke, and death. Therefore, this infusion route should be used by trained professionals in the appropriate setting.

Fig 2. Treatment of refractory anaphylaxis. Reproduced with permission of Resuscitation Council UK. ALS = advanced life support; BP = blood pressure; CPR = cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ECG = electrocardiography; HR = heart rate; IO = intraosseous; IV = intravenous; SpO2 = oxygen saturation.

| Mast cell tryptase measurement |

There are several differential diagnoses of anaphylaxis, and measurement of an elevated mast cell tryptase can be very helpful in supporting the diagnosis over alternatives. Despite this, it is not useful in the initial recognition of the condition.

Ideally three samples should be taken: the first as soon as possible (without delaying treatment), the second 1 to 2 hours (but not more than 4 hours) after the onset of symptoms and a third at least 24 hours after the complete resolution.

| Guidance regarding duration of observation after anaphylaxis and timing of discharge |

Patients who have been treated for suspected anaphylaxis should be observed in a clinical area with facilities to treat life-threatening ABC problems, as some experience more symptoms after resolution.

Biphasic reactions can occur many hours after the initial reaction; Published studies report a median of 12 hours. Patients over 16 years of age should be observed for 6 to 12 hours after the onset of initial symptoms, although more recent evidence suggests that this time should be prolonged.

All patients should be seen by an experienced doctor and discharged with advice on the symptoms of anaphylaxis and what to do if it occurs again, receive two adrenaline auto-injectors or have replacements available if they have been used, allow a demonstration of how use auto-injectors and give them a written emergency treatment or action plan.

| Conclusions |

The use of adrenaline in the initial treatment of anaphylaxis is universally accepted. The new guideline further emphasizes the importance of its use and the need to avoid interventions that may delay the adequate and appropriate administration of this drug.

Antihistamines can be used as a third-line treatment to reduce skin involvement, but only after successful treatment of ABC features.

Corticosteroids are not helpful and emerging evidence suggests they may worsen outcomes when used routinely; therefore, its application is limited to the treatment of anaphylaxis in the setting of poorly controlled asthma and refractory anaphylaxis.

There is a new treatment algorithm for refractory anaphylaxis, which provides an easy reference for the settings in which this may occur.

Finally, there is more nuanced advice regarding observation after anaphylaxis, which takes into account risk factors and circumstances under which delayed or recurrent symptoms may be experienced.