Aim

To evaluate whether maternal intake of ultra-processed foods during pregnancy and during the parenting period is associated with the risk of overweight or obesity in children during childhood and adolescence.

Design Population-based prospective cohort study. Nurses Health Study II (NHSII) and the Growing Up Today Study (GUTS I and II) in the United States.

Participants

19,958 mother-child pairs (45% boys, 7 to 17 years of age at study enrollment) with a median follow-up of 4 years (interquartile range 2 to 5 years) to age 18 or emergence of overweight or obesity, including a subsample of 2925 mother-infant pairs with information on perigestational diet.

Main outcome measures

Multivariable-adjusted log-binomial models with generalized estimating equations and an exchangeable correlation structure were used to account for correlations between siblings and to estimate the relative risk of overweight or obesity in offspring as defined by the International Obesity Task Force.

Results

2471 (12.4%) children developed overweight or obesity in the entire analytical cohort. After adjusting for established maternal risk factors and offspring’s intake of ultra-processed foods, physical activity, and sedentary time, maternal consumption of ultra-processed foods during the parenting period was associated with overweight or obesity in offspring. with a 26% higher risk in the children of the group with the highest maternal consumption of ultra-processed foods (group 5) versus the group with the lowest consumption (group 1; relative risk 1.26, 95% confidence interval 1.08 a 1.47, P for trend <0.001).

In the subsample with information on perigestational diet, although rates were higher, peripregnancy ultraprocessed food intake was not significantly associated with an increased risk of overweight or obesity in offspring (n=845 (28.9%) ; group 5 vs. group 1: relative risk 1.17, 95% confidence interval: 0.89 to 1.53, P trend = 0.07).

These associations were not modified by age, sex, birth weight, and gestational age of the offspring or by maternal body weight.

Conclusions Maternal consumption of ultra-processed foods during the parenting period was associated with an increased risk of overweight or obesity in offspring, independent of maternal and offspring lifestyle risk factors. Further studies are needed to confirm these findings and understand the underlying biological mechanisms and environmental determinants. These data support the importance of refining dietary recommendations and developing programs to improve the nutrition of women of reproductive age to promote offspring health. |

Comments

Dietary guidelines must be refined and financial and social barriers removed to improve the nutrition of women of childbearing age, researchers say.

A mother’s consumption of ultra-processed foods appears to be linked to an increased risk of overweight or obesity in her offspring, regardless of other lifestyle risk factors, suggests a US study published today by The BMJ .

Researchers say more studies are needed to confirm these findings and understand the factors that could be responsible. But they suggest that mothers could benefit from limiting their consumption of ultra-processed foods, and that dietary guidelines should be refined and financial and social barriers removed to improve the nutrition of women of childbearing age and reduce childhood obesity.

According to the World Health Organization, 39 million children were overweight or obese in 2020, increasing the risks of heart disease, diabetes, cancer and premature death.

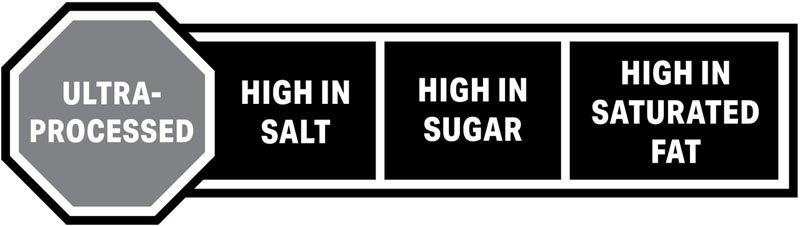

Ultra-processed foods, such as baked goods and packaged snacks, soft drinks, and sugary cereals, are commonly found in modern Western diets and are associated with weight gain in adults. But it’s unclear whether there is a link between a mother’s consumption of ultra-processed foods and the body weight of her offspring.

To explore this further, the researchers drew on data from 19,958 children born to 14,553 mothers (45% boys, ages 7 to 17 at study enrollment) from the Nurses’ Health Study. II (NHS II) and the Growing Up Today Study (GUTS I and II) in the United States.

NHS II is an ongoing study tracking the health and lifestyles of 116,429 U.S. registered nurses ages 25 to 42 in 1989. Since 1991, participants have reported what they ate and drank, using self-report questionnaires. Food frequency validated every four years.

The GUTS I study began in 1996 when 16,882 children (aged 8 to 15 years) of NHS II participants completed a baseline health and lifestyle questionnaire and were monitored every year between 1997 and 2001, and every two years thereafter. from then on.

In 2004, 10,918 children (aged 7 to 17 years) from NHS II participants joined the expanded GUTS II study and were followed in 2006, 2008, and 2011, and every two years thereafter.

A variety of other potentially influential factors, known to be strongly correlated with childhood obesity, were also taken into account. These included mother’s weight (BMI), physical activity, smoking, living status (with or without a partner) and partner’s education, as well as consumption of ultra-processed foods, physical activity and sedentary time. of the kids. Overall, 2471 (12%) children became overweight or obese during an average follow-up period of 4 years.

The results show that a mother’s consumption of ultra-processed foods was associated with an increased risk of overweight or obesity in her offspring.

For example, a 26% higher risk was observed in the group with the highest maternal consumption of ultra-processed foods (12.1 servings/day) compared to the group with the lowest consumption (3.4 servings/day).

In a separate analysis of 2,790 mothers and 2,925 children with dietary information from 3 months before conception until delivery (peripregnancy), the researchers found that peripregnancy intake of ultra-processed foods was not significantly associated with an increased risk. overweight or obesity in children.

This is an observational study, so it cannot establish cause, and the researchers recognize that some of the observed risk may be due to other unmeasured factors, and that self-reported measures of weight and diet may be subject to misreporting.

Other important limitations include the fact that some offspring participants were lost to follow-up, resulting in some of the analyzes being underpowered, particularly those related to perigestural intake, and that the mothers were predominantly white and from similar social and economic backgrounds, so the results may not apply to other groups.

However, the study used data from several large ongoing studies with detailed dietary assessments over a relatively long period, and further analysis produced consistent associations, suggesting that the results are robust.

The researchers do not suggest any clear mechanism underlying these associations and say the area deserves further investigation. However, these data “support the importance of refining dietary recommendations and developing programs to improve the nutrition of women of reproductive age to promote the health of their offspring,” they conclude.