Summary Bipolar disorder (BD) is a potentially chronic mental disorder characterized by recurrent manic and depressive episodes, disruption of circadian rhythm, and changes in energy metabolism. “ Metabolic jet lag” refers to a state of change in circadian patterns of energy homeostasis, affecting neuroendocrine, immune and adipose tissue function, expressed through behavioral changes, such as irregularities in sleep and appetite. Risk factors include genetic variation, mitochondrial dysfunction, lifestyle factors, poor gut microbiome health, and abnormalities in hunger, satiety, and hedonic function. Evidence suggests that metabolic jet lag is a central component of the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder (BD), as people with BD frequently present with irregular eating rhythms and circadian desynchronization of their energy metabolism, which is associated with unfavorable clinical outcomes. . Although current diagnostic criteria lack an assessment of feeding rhythms, technological advances, including mobile phone applications and ecological momentary assessment, allow reliable monitoring of biological rhythms. Overall, methodological refinement of metabolic jet lag assessment will increase knowledge in this field and stimulate the development of interventions targeting metabolic rhythms, such as time-restricted feeding. |

Bipolar disorders ( BD) are a group of common, complex, multidimensional mental disorders that affect mood, cognition, and behavior. They are classified into two main types, TB type I and TB type II. BD type I is characterized by the presence of one or more manic episodes , while BD type II includes both a hypomanic episode and a major depressive episode . The depressive components of any of the subgroups are the most frequent and difficult to treat. Depression in BD is more likely to be accompanied by atypical symptoms , such as increased sleep and appetite, as well as fatigue.

The implications for those affected by these disorders are significant, as it affects their physical and mental health, as well as being inconsistent in nature, making it difficult to both live with and treat the disorder. Ideal treatment strategies should address manic and depressive symptom clusters, treat acute episodes, prevent relapses and recurrences, restore functioning, and cause limited or no side effects. These goals are not always achieved by people living with BD, even with the adoption of evidence-based approaches.

Although it is often called a mood disorder , the mental and behavioral manifestations of BD go far beyond mood.

People with BD exhibit widespread dysfunction in multiple central and peripheral systems , including abnormalities in arousal, attention, cognition, neuroendocrine function, and even neurostructural changes. Another dimension of BD psychopathology is the alteration of the circadian rhythm , with changes in the sleep-wake cycle being the most replicated. Most people with TB exhibit different degrees of circadian desynchronization at different times in their disease trajectory, resembling jet lag through unfavorable side effects such as abnormal sleep, metabolic disturbances, and low energy. Furthermore, there is a bidirectional relationship between circadian disruption and manic and depressive symptoms, with sleep deprivation being a trigger for manic symptoms and mood episodes accompanied by circadian dysfunction. One of the most important disease triggers is jet lag.

Circadian rhythms are influenced both by the main endogenous biological clock, a distinct group of cells located in the anterior hypothalamus , and by information from both internal and external inputs, through light, sounds, diet , exercise and the programming of activities. The neurobiological underpinnings of this association include, but are not limited to, genetic factors, chronotypes, presence of sleep disorders (e.g., obstructive sleep apnea), hormones (e.g., melatonin), and inflammatory immune mediators. The genetic control of circadian rhythm maintenance is composed of a molecular feedback loop of approximately 20 genes, known as “clock genes . ”

Studies have suggested a role for the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) and related genes in emotional regulation. Additionally, disruptions in the circadian rhythm have been linked to a variety of adverse health effects, including metabolic and mood disorders. Metabolic syndrome is approximately twice as common in BD compared to the general population and is associated with worsened mood symptoms, reduced treatment efficacy, and an unfavorable clinical course. Additionally, dysfunctional circadian rhythms have been linked to increased susceptibility to mood swings and resistance to treatment. It is evident that there is a complex and multidirectional relationship between circadian clock synchrony, metabolic homeostasis, and mood disorders.

The study of energy intake and expenditure in mood disorders represents a unique opportunity to integrate transdisciplinary lines of research, such as chronobiology and metabolic physiology, with the aim of improving patient outcomes. The objective of this study is to comprehensively review the clinical and mechanistic findings from different lines of evidence that suggest that imbalances in the rhythmic regulation of metabolic processes are involved in the pathophysiology of BD and to discuss the implications of these findings for research and management. clinical care.

The concept of metabolic jet lag

" Metabolic jet lag" is a concept recently introduced in the literature, which designates a state of dramatic change in the circadian patterns of energy homeostasis, including, among others, hormone release, adipose tissue function and immune system that is expressed through behavioral changes that include irregular sleeping and eating. Under physiological conditions, metabolic rhythms are related to cyclic changes in biochemical pathways that are integral for the body to respond to environmental changes that occur during the night and day cycles. The existence of such changes is believed to provide organisms with an important evolutionary advantage, allowing the body to anticipate nutrient needs and ensure optimal energy capacity during active hours of the day.

Metabolic jet lag constitutes a desynchronization between external cues and the temporal order of the master circadian clock and has been linked to a variety of detrimental health outcomes. For example, it is well known that shift workers or people who constantly travel between time zones are disproportionately affected by coronary heart disease, obesity, and metabolic syndrome. On the contrary, people affected by weight gain and obesity are more prone to circadian rhythm disturbances. The bidirectional link between circadian rhythm and metabolic health adds to the complexity in understanding the underlying mechanisms.

Several factors are involved in the pathophysiology of metabolic jet lag . The most relevant ones are described in the following sections.

Genetic predisposition

BD is known to be an inherited mood disorder, and it has recently been suggested that circadian disruption, a risk factor for BD, may also be inherited. The circadian rhythm is regulated by a variety of transcription and translation pathways, described in detail elsewhere.

Irregular feeding rhythms

The timing of energy intake is an important peripheral signal that influences the regulation of circadian function. Adjusting regular meal times can reset peripheral clocks. In fact, a disorganized eating pattern is both an indicator and contributor to metabolic jet lag, which is linked to an increased risk of obesity, metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus, and even some forms of cancer.

Eating rhythms have been shown to influence body weight and energy metabolism even when the same amount of food is consumed because energy balance does not promote expenditure during nighttime hours and therefore calories are stored as fat . Weight gain and increased risk of cardiometabolic diseases have been observed regardless of total food intake when eating patterns were not synchronized with the CNS clock. Studies in rodents have shown that restoring meal timing during the active phase improves metabolic abnormalities associated with jet lag and reduces obesity, indicating a protective effect of routine feeding.

Anomalies in the hunger/satiety cycle and hedonic aspects

In humans, the behavior of obtaining food and eating is highly complex and requires the integration of multiple systems. For example, it requires the interpretation of interoceptive inputs, such as sensations of hunger and satiety, that dynamically fluctuate over time as a function of energy state. It also has to be integrated with the hedonic aspects of eating, which are partially independent of energy needs. Viewed through an evolutionary lens, food acquisition requires activity to facilitate food gathering (e.g., foraging) and navigation of associated risks (e.g., hunting).

Eating according to socially determined times also requires learning and memory that depend at least partially on the activity of the hippocampus , through the integration of past experiences with current signals from exteroception and internal energy balance. The hypothalamus plays an important role in the learned control of eating behavior, highlighted by the inability of subjects with bilateral hippocampal damage to interpret interoceptive inputs such as hunger and satiety. A disconnect between energy requirements and hunger interpretation was observed as hunger indices were maintained across feeding phases. This confirmed that these systems can process independently but require communication to operate effectively. In general, negative health consequences arise if humans do not sufficiently receive or interpret energy requirements, including metabolic jet lag.

Nutritional content

Although meal timing is important for maintaining metabolic synchrony with the circadian clock, studies have also indicated an important role for nutritional content . Specifically, diets high in fat and sugar have been linked to alterations in circadian rhythms. In animals, 1 week of a high-fat diet was sufficient to cause a prolongation of the circadian period compared with a regular diet, an effect that was independent of changes in body weight. More recently, studies have indicated an underlying mechanism for this observation in which the nutritional content of foods has been shown to alter the expression of clock genes. For example, obesity caused by a high-fat diet was shown to alter the expression of clock genes in the liver and kidneys. Furthermore, disruption of intestinal L cells and pancreatic beta cells was demonstrated in mice following obesogenic feeding, providing some explanation for the development of metabolic abnormalities on a high-fat diet.

Gut Microbiome Health

The gut microbiome may be a factor by which diet and meal timing affect metabolic and circadian dysfunction. The composition and function of the gut microbiome oscillates with the 24-hour clock. The intestinal epithelium interacts with different microbes throughout the day and some bacteria are even carried along with melatonin levels. Furthermore, a bidirectional relationship has been proposed in which the microbiome may also influence clock gene expression in response to diet.

Sedentary lifestyle

Another facet of lifestyle that can predispose an individual to metabolic jet lag includes insufficient exercise or a sedentary lifestyle which has been linked to a lack of synchrony between metabolism and the circadian cycle. In humans, physical activity exhibits a circadian cycle of approximately 24 hours and acts as a zeitgeber to synchronize circadian clocks in peripheral tissues such as skeletal muscle, liver, and lungs. This has been confirmed in animal and human studies. From an evolutionary perspective, energy metabolism is optimized throughout the day-night cycle to allow humans to travel long distances in search of food during waking hours. Conversely, limited physical activity may indicate that the body is recovering from injury or illness and is associated with inflammatory responses . Therefore, energy expenditure responds to environmental adversity and is also an important external signal for maintaining circadian synchronization.

Sedentary lifestyles are associated with a variety of unfavorable health effects, including cardiometabolic problems such as worsening glycemic control, blood pressure, and triglyceride levels. Sedentary activity is reported to significantly increase glucose and insulin resistance in participants after just 5 days, including a 67% greater insulin response to a glucose load. Exercise is a health promoter in humans, as well as an important circadian timing signal. Therefore, it is important to consider the widespread benefits of physical activity in resisting the development of metabolic jet lag.

Alterations in mitochondrial metabolism

Mitochondria are organelles responsible for energy generation in eukaryotic cells. Dysfunctional mitochondrial function has been consistently demonstrated in several serious mental disorders, including BD. Indeed, BD is often conceptualized as a mitochondrial disorder , where mania and depression are considered states of up- and down-regulation of mitochondrial function, respectively. Furthermore, the prevalence of TB in mitochondrial diseases is about 20 times higher than in the general population. Mitochondria from individuals with TB show significant differences in morphology and dynamics compared to healthy individuals.

Current evidence suggests that mitochondria are influenced by the circadian rhythm and exert effects on biological rhythms. Circadian factors are known to be critical regulators of mitochondrial function and demonstrate an important role in maintaining metabolic health.

Bipolar Disorder (BD) as a disease of deregulated energy expenditure

A high prevalence of metabolic abnormalities in individuals with BD, especially those with multiple mood episodes, is well documented.

Metabolic abnormalities are common in the mood disorder population, with approximately 50% of patients having obesity, diabetes mellitus, and/or insulin resistance. Although there is a well-documented influence of iatrogenic and lifestyle factors on metabolic dysfunction in BD, they do not explain all the observed differences. For example, people with TB exhibit severe metabolic abnormalities even in the absence of pharmacotherapy . Metabolic dysfunction is believed to be a central component of the pathophysiology of the disease and contributes significantly to mortality in individuals with TB, including higher rates of death from cardiovascular disease compared to the general population. Understanding the etiology of metabolic abnormalities will allow prevention of further disease progression, limiting mortality in these individuals.

Taking these data together, it is not unexpected that replicated evidence indicates that energy metabolism plays a critical role in both normal and abnormal brain function. The human brain constitutes 2% of body mass but consumes 25% of energy substrates, suggesting that changes in energy regulation significantly affect neural function. Furthermore, evidence indicates that brain energy metabolism plays an important role in human behavior, through the control of both energy intake and expenditure. Certain neural networks, including dopamine transmission in corticostriatal pathways, are considered a potential mechanism explaining this finding, as well as indicators of energy status, such as glucose and insulin. In fact, studies have linked disruption of insulin signaling in the brain to reduced dopamine transmission and symptoms of altered mood.

Research has repeatedly shown that people with mood disorders exhibit abnormal brain energy metabolism. For example, markers of dysfunctional energy regulation have been identified in individuals with mood disorders that include increased lactate and lower pH, as well as oscillating energy generation in which body temperature is higher in mania and more low in depression. Furthermore, reduced brain glucose metabolic rates have been identified during depressive episodes in both major depressive disorder and BD.

As a result of dysfunctional energy metabolism in mood disorders, evidence indicates that molecular and cellular pathways mediating energy expenditure are downregulated. Behaviorally, this has been expressed as reduced physical activity during depressive episodes, revealed through accelerometry studies. Furthermore, people with mood disorders exhibit a reduced willingness to exert physical effort to obtain rewards compared to healthy controls, indicating motivational changes and reward system dysfunction .

Recent work has associated this finding with altered peripheral insulin signaling in people with depression, although more work is needed to identify a mechanistic link. According to the “selfish brain” theory , glucose utilization is prioritized for the brain through inhibition of insulin secretion from the pancreas. This mechanism improves glucose uptake in the central nervous system, which is an insulin-independent process. Therefore, reduced physical activity in individuals with altered brain energy regulation may signify another compensatory mechanism that acts to conserve energy in states of homeostatic imbalance such as those observed in mood disorders.

Insulin is a key hormone involved in the regulation of brain energy metabolism, mediating food intake, energy expenditure , adipose tissue accumulation, and peripheral metabolism. Brain insulin signaling has also been implicated in the mesolimbic dopamine system and influences brain activity related to reward behavior. Therefore, the actions of insulin demonstrate great relevance for the study of the etiology of mood disorders. In fact, brain insulin resistance has already been described as a potential mechanism for mood abnormalities. Despite this evidence, to our knowledge, no study has yet to evaluate the relationship between brain insulin signaling and energy expenditure in people with TB.

Bipolar Disorder (TB) as a disease of metabolic delay

Historically, circadian rhythms of energy regulation have allowed our human ancestors to allocate metabolic resources according to the occurrence of activities throughout the day and night cycle. The influence of metabolic jet lag is increasingly relevant to humans as we continue to adopt social and personal habits that deviate from the diurnal cycle and excel in the rest period. Misalignment between internal physiology and behavior is detrimental to many aspects of human health. The high prevalence and impact of metabolic dysfunction in people with TB supports the view that metabolic jet lag may be a key aspect of disease pathophysiology and progression.

Metabolic abnormalities are significantly higher in BD compared to the general population and have been linked to unfavorable disease trajectories. Specifically, laboratory markers indicate elevated levels of serum triglycerides and glycosylated hemoglobin, hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance, and low levels of HDL, compared to healthy controls. These elevated blood markers of metabolic syndrome have been associated with reduced treatment effectiveness and worsening disease course in TB. People with TB also show a higher prevalence of obesity compared to the general population. Obese people with TB are more likely to have major depressive episodes, accumulate medical conditions, and become resistant to treatment. Studies have revealed evidence of structural and neurobiological changes associated with obesity that may contribute to the progression of BD, although more work is needed to identify the exact underlying mechanisms responsible.

Abnormalities in insulin and glucose regulation are also routinely observed in people with TB, related to worsening mood symptoms and reduced therapeutic efficacy of lithium. In fact, a diagnosis of type II diabetes mellitus is three times more common in individuals with TB compared to healthy individuals. As a hormone that acts within brain regions such as the amygdala, hypothalamus, and hippocampus, altered insulin signaling can disrupt the healthy functioning of neural tissues. Specifically, it is believed that reduced insulin sensitivity can lead to neurodegeneration in the aforementioned regions. Cognitive impairment has also been linked to insulin resistance in people with TB, further supporting this point.

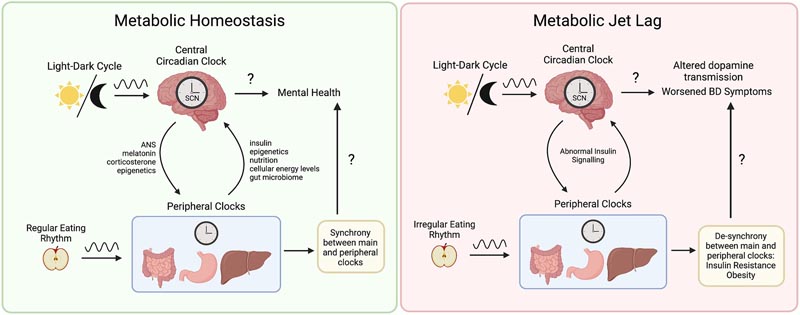

A less studied circadian somatic change in BD is related to appetite , which can differ widely in hypomanic, manic, and depressive episodes, similar to sleep-wake cycle abnormalities. Recent work has identified desynchronized circadian eating behavior as a prominent subgroup of BD, associated with more severe metabolic comorbidities and mood symptoms. Under physiological conditions, most of us exhibit a rhythmic pattern in eating behaviors. However, patients with TB frequently describe oscillations or abnormalities in their appetite and eating habits, but most of these abnormalities have not been sufficiently explored. Few studies have investigated eating rhythms in people with mental disorders, other than anorexia and bulimia, and very few of them were conducted in populations with BD. Regular meal timing is an important external cue for the circadian system; therefore, changes in appetite may promote adverse effects along with circadian misalignment, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 . Metabolic jet lag as a central component of the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder (BD). Synchrony between the central and peripheral clocks is maintained by external cues, such as the light-dark cycle and regular feeding patterns. The central circadian clock influences peripheral tissues through the autonomic nervous system, neurohormones such as melatonin and corticosterone, as well as epigenetic mechanisms such as the control of gene expression of metabolic enzymes. In contrast, metabolic function also influences the central circadian clock through insulin signaling, control of clock gene expression, mitochondrial function, energy expenditure, nutritional content, energy levels. cellular and through the gut-brain axis. Eating rhythms that are irregular and do not align with the light-dark cycle contribute to a variety of metabolic dysfunctions including insulin resistance and obesity. As a result, abnormal insulin signaling has been linked to neurobiological changes, including altered dopamine transmission. Ultimately, metabolic jet lag contributes to a worsening clinical course of BD, including reduced quality of life and treatment effectiveness, more frequent mood episodes, and shorter lifespan. The exact mechanisms underlying metabolic jetlag and worsening of TB symptoms remain unknown. The exact mechanisms underlying metabolic jetlag and worsening of TB symptoms remain unknown. The exact mechanisms underlying metabolic jetlag and worsening of TB symptoms remain unknown.

Preliminary investigations using simple questionnaires suggest that feeding rhythm dysfunction is present in BD during acute episodes and euthymia. This has been associated with symptom severity and poor quality of life. It has been shown that, although sleep disturbance is prevalent in BD, disruption of eating rhythms is more strongly associated with executive functioning than with sleep rhythms in the interepisodic period. Overall, it is important to assess the alignment of internal and external cues in people with TB and there is a need to better understand the role of dietary rhythms and metabolic jet lag.

Implications for research and clinical care

Considerations on metabolic jet lag and its role in the pathophysiology of BD are an important avenue for future research. Clinically, incorporating assessment of eating rhythms is an important step for people with TB, especially considering common comorbidities that affect eating behavior, such as sleep-wake disorders, alcohol use disorders, substances and eating disorders.

Improvements in the clinical evaluation of feeding rhythms

Currently available studies use very simple assessments in assessing eating rhythms, including food diaries, 24-hour recalls, and food frequency questionnaires . Food diaries are often tedious and place a great burden on both the participant and the researcher, as well as a challenge for long-term compliance. Furthermore, 24-hour recalls are often confused with aspects of episodic memory and data interpretation with recall bias creating a significant threat to the accuracy of the results. Finally, food frequency questionnaires cannot fully assess eating patterns due to lack of contextual information. Technological advances, such as data entry applications and food tracking websites, have reduced some of the burden associated with manual food tracking, although participant participation is still required.

Using ecological momentary assessment

The aforementioned methods contrast with the development of more sophisticated tools used to assess diet and nutrition, especially considering the current availability of smartphone applications that can be used for active and passive monitoring of lifestyle factors, such as part of a digital phenotyping approach . For example, ecological momentary assessment (EMA) is an active monitoring method in which human behavior is measured in a participant’s natural environment, such as via a mobile phone. This method allows for real-time assessment of behaviors such as feeding patterns over a given period, possibly aiding in the early identification of abnormalities. EMA requires little effort on the part of the participant and avoids the effects of recall bias that are associated with other self-report methods, making it more effective than the standard food diary.

EMA has been used in a variety of contexts, such as to identify the effects of fasting on eating disorders and the underlying cognitive aspects that may explain eating disorder behavior. Digital phenotyping also encompasses methods of collecting data passively, that is, not requiring active input from the user, as is the case with EMA. These methods typically use a person’s personal device, sometimes in conjunction with wearable sensors. This assessment method uses data streams related to social activity, movement, and biological rhythms to identify human behavioral phenotypes. Digital phenotyping demonstrates significant potential for capturing intra-individual differences over time, as well as improving early detection of mood disorders and predicting health outcomes following clinical intervention. Overall, more work is needed to determine the optimal technology for measuring biological rhythms such as eating, as well as implement its use in clinical TB evaluation.

The integration of chronobiology in the study of mitochondrial dysfunction in TB

Although mitochondrial function and dysfunction have been previously investigated in BD, to our knowledge, no study has incorporated a chronobiological approach. It would be very helpful to understand whether circadian lifestyle factors such as meal timing, exercise and sleep can beneficially modulate mitochondrial function in BD and, by extension, whether they may also be beneficial for comorbidities. general doctors.

Exploration of eating rhythms as an intervention objective

Additional research is required to identify more effective intervention strategies for the management of BD, especially for patients exhibiting circadian desynchronized eating. Furthermore, the potential for adverse effects of pharmacotherapy on energy balance supports the need for complementary approaches to the prevention and treatment of metabolic comorbidities. Non-pharmaceutical interventions, especially those related to lifestyle choices, could support positive changes for those suffering from this serious problem that affects more people than reported. For example, interpersonal and social rhythm therapies have been shown to improve mood symptoms and prevent relapse in BD by helping patients establish routines to stabilize their circadian rhythms.

Time-restricted feeding ( TRE) refers to the restriction of the diurnal feeding window to 12 to 20 hours and demonstrates benefits in multiple aspects of human physiology, including the potential to counteract metabolic jet lag. Although few studies of ERT have been performed in humans, there is evidence that brain function and peripheral energy metabolism can be optimized with this method, including the promotion of ketone body synthesis. The role of ketone bodies in the brain has been linked to improved energy metabolism and ketosis is an increasingly attractive therapeutic target in BD. In addition, TRE allows the regulation of fat metabolism through hormones involved in mood, such as leptin, adiponectin and ghrelin. ERT can be used to counteract certain metabolic abnormalities that have been linked to worsening mood disorder symptoms and the limited eating window allows a means to overcome circadian desynchronized eating.

Conclusion Disruptions in the circadian rhythm negatively affect metabolic processes, and this is relevant for people with TB. Sleep-wake and feeding-fasting cycles are affected by disruption of the circadian rhythm and are disrupted as hallmarks of BD, but it is not yet clear whether the disruption is the result of physiological differences in people with BD, or whether it is a factor that contributes to related disturbances. This review has explored important findings related to BD and the prevalence of metabolic dysfunction in this patient population, suggesting that altered energy regulation is a key factor contributing to the pathophysiology of the disease. People with TB often show signs of metabolic jet lag , and more work is needed to determine the link between biological rhythms, such as meal timing, and disease progression. Furthermore, it may be possible to limit unfavorable disease progression with interventions such as time-restricted feeding (TRE), which improve synchronization between energy metabolism and the circadian clock. As an emerging field of medicine, chrononutritional approaches to psychiatry show potential to improve BD symptoms, especially considering the unpredictable nature of pharmacological interventions and associated treatment resistance. As a 24-hour society, more research is needed to delineate the role of rhythm disruption in psychiatric illness. |