Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is the treatment of choice for the management of common bile duct (CBD) stones, generally through biliary sphincterotomy and balloon extraction. However, difficult bile duct stones (i.e., stones larger than 10 mm in diameter, barrel-shaped stones, or stones in patients with a conical bile duct) represent a challenge, even for highly experienced endoscopists, and are associated with the frequent need for additional procedures such as mechanical lithotripsy or cholangioscopy-assisted lithotripsy for stone fragmentation and recovery.

Beyond mechanical lithotripsy, endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation (EPLBD), either with or without biliary endoscopy prior sphincterotomy and single-operator cholangioscopy (SOC) with laser lithotripsy or electrohydraulic lithotripsy, have also been proposed to address cases. difficult to extract.

Currently, international guidelines recommend limited sphincterotomy followed by EPLBD as the first-line approach for difficult gallstones because it decreases the need for mechanical lithotripsy by 30% to 50% with similar success rates compared to endoscopic sphincterotomy alone but with a lower incidence of adverse events compared to large sphincterotomy.

On the other hand, the development of SOC in recent years has led to its implementation, combined with laser or electrohydraulic lithotripsy, for the treatment of difficult bile duct stones, with an estimated elimination of 88%.

Mainly because of its costs, SOC + laser lithotripsy/electrohydraulic lithotripsy is currently recommended after failure to achieve complete stone removal using EPLBD and/or mechanical lithotripsy.

There is still limited evidence on the comparative effectiveness of the aforementioned techniques. This systematic review compared the efficacy and safety of different endoscopic techniques for the management of patients with large CBD stones .

Methods

Nineteen randomized controlled trials (2752 patients) comparing different options for the treatment of large gallstones (>10 mm) (endoscopic sphincterotomy, balloon sphincteroplasty, sphincterotomy followed by endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation [S+EPLBD], mechanical lithotripsy, single operator cholangioscopy [SOC]) with each other.

The outcomes of the study were the success rate of stone removal and the incidence of adverse events. Pairwise and network meta-analyses were performed for all treatments, and recommendation, development, and evaluation classification criteria were used to analyze the quality of the evidence.

Results

All treatments except mechanical lithotripsy significantly outperformed sphincterotomy in stone removal rate (risk ratio [RR], 1.03–1.29). SOC was superior to other adjunctive interventions (vs balloon sphincteroplasty [RR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.07–1.45], vs S+EPLBD [RR, 1.23; range, 1. 06-1.42] and versus mechanical lithotripsy [RR, 1.34; range, 1.14–1.58]).

Cholangioscopy ranked highest in increasing stone removal success rate (surface below cumulative [SUCRA] score, 0.99) followed by S+EPLBD (SUCRA score, 0.68). SOC and S+EPLBD outperformed the other modalities when only studies reporting stones larger than 15 mm were taken into consideration (SUCRA scores, 0.97 and 0.71, respectively).

None of the interventions evaluated were significantly different in the rate of adverse events compared to endoscopic sphincterotomy or other treatments. Pancreatitis and post-ERCP bleeding were the most common adverse events ( table 1 ).

| Stone Removal Success Rate | Adverse event rate | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| S.O.C. | 0.99 | S.O.C. | 0.76 |

| S+EPLBD | 0.68 | S+EPLBD | 0.75 |

| Sphincteroplasty | 0.50 | Sphincteroplasty | 0.47 |

| mechanical lithotripsy | 0.26 | Sphincterotomy | 0.40 |

| Sphincterotomy | 0.06 | mechanical lithotripsy | 0.10 |

Table 1 . SUCRA score classification for stone clearance success rate and adverse event rate.

Discussion

In the present study, through a network meta-analysis and using GRADE criteria to assess the quality of evidence, several key observations were made regarding the optimal approach for patients with large gallstones during ERCP.

First, all treatments except mechanical lithotripsy significantly outperformed endoscopic sphincterotomy in terms of stone removal rate. On the other hand, moderate-quality evidence suggests that only SOC had better outcomes than all other complementary treatments. As a consequence, SOC ranked first in increasing stone removal success rate (SUCRA score, 0.99), followed by S+EPLBD (SUCRA score, 0.68).

Second, the superiority of SOC over the other treatments remained significant in patients with larger stones. (>15 mm), and proved to be the only valuable therapeutic option that resulted in consistent improvement over the other modalities, again supported by moderate quality evidence. The only alternative that was shown to be superior to endoscopic sphincterotomy in this context was S+EPLBD, which again ranked as the second option even in the case of larger stones.

This was a critical observation because SOC, despite its recent widespread implementation, is still not available in all environments and requires additional training with a learning curve to achieve expertise. Furthermore, despite its effectiveness, SOC could prolong exam time, as has been recently demonstrated. This could lead to an increased need for patient sedation, which is not always desirable or possible in all cases. Finally, the cost of the procedure is another factor to take into account. In a recent study it was shown that SOC was significantly more expensive in terms of procedural supplies.

Third, low-quality evidence suggested that no differences were observed between the interventions tested in terms of rates of adverse events, either in direct or indirect comparisons, with only mechanical lithotripsy resulting in the lowest value (SUCRA score, 0.10) in the ranking with respect to this specific result. However, the imprecision of the estimates observed in mechanical lithotripsy trials suggests that the evidence supporting the aforementioned finding is of very low quality, so special caution is required when interpreting these results.

Among reported adverse events, post-ERCP pancreatitis and bleeding were the most common adverse events, while only one fatal event was observed in 1 trial in a patient treated with endoscopic sphincterotomy who died of cardiorespiratory failure after randomization to sphincterotomy. endoscopic.

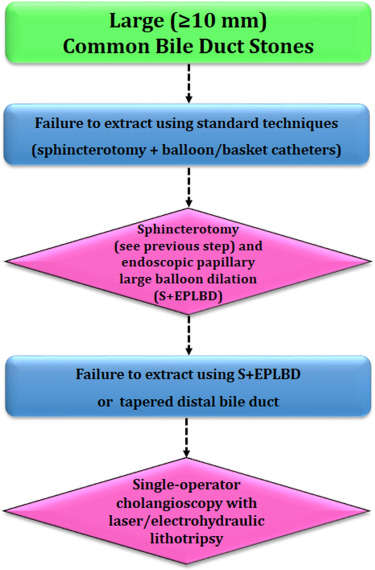

Based on the key observations, an algorithm is proposed ( figure 1 ) for the management of large and/or difficult stones, in which sphincterotomy followed by endoscopic papillary dilation with a large balloon should be applied as the first method to extract large stones from the common bile duct SOC with laser or electrohydraulic lithotripsy should be the most advanced approach in case of failure or when a tapered distal bile duct does not allow dilation with a large balloon.

Another strength of this study was the fact that, in addition to including only RCT data, an objective critical appraisal of the overall quality of the evidence was performed using the standardized GRADE methodology. The main reason preventing the evidence from being of higher quality was due to the unblinded design of the included RCTs, a bias commonly found in endoscopic studies, in which operator blinding is generally not feasible. However, we believe that this critical evaluation could guide future recommendations to clinicians and inform upcoming guidelines.

There were certain limitations related to both the network analysis and the individual studies that deserve further discussion. First, the paucity of head-to-head trials and the moderate heterogeneity observed for certain comparisons resulted in low to moderate quality evidence for the comparative effectiveness of the different methods. Second, network meta-analyses may be subject to misinterpretation due to conceptual heterogeneity, related to considerable differences in participants, interventions, co-interventions/baseline treatment, and outcome assessment, which may limit the comparability of the essays.

On the other hand, and as already mentioned, a stone can also be characterized as difficult not only because of its size, but also because of its shape (e.g., barrel-shaped) or because of its difficulty in removing it, due to the shape of the bile duct (e.g., in patients with a conical CBD, which may be an obstacle to stone extraction, even when the stone is not excessive in size per se). Finally, the intrahepatic location of the stones usually constitutes another group of “difficult stones.”

Finally, when considering all possible endoscopic techniques used for the management of difficult stones, the use of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy in combination with ERCP techniques had to be ignored because no RCTs were available. This option, however, may be part of the arsenal when it becomes available locally.

Figure 1 . Algorithm proposal for the treatment of stones measuring 10 mm or larger. S+EPLBD, sphincterotomy plus endoscopic papillary dilation with large balloon.

Conclusion The present work evaluated the methods applied in the management of large gallstones. Although the robust GRADE methodology showed only a low to moderate level of evidence, we observed that SOC was more effective than other methods, particularly in patients with larger stones, while S+EPLBD could represent a less expensive and more widely available alternative. |