Sepsis is defined as a life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection.

In this context, biomarkers could be considered as indicators of infection, dysregulated host response, response to treatment, and/or help clinicians predict patient risk.

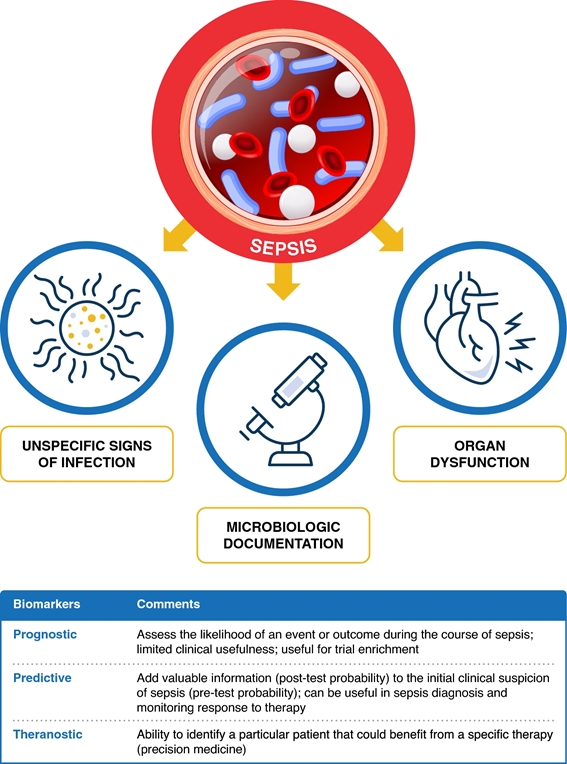

In daily practice, for the diagnosis and management of sepsis, as well as for the administration of antibiotics, doctors combine data from different sources that result from the intersection of three vectors ( Fig. 1 ): systemic manifestations , organ dysfunction and documentation microbiological . Biomarkers could provide additional information on the vector of systemic manifestations (host response biomarkers, e.g., C-reactive protein-CRP and procalcitonin-PCT), organ dysfunction (e.g., kidney injury biomarkers), and microbiological documentation ( pathogen-specific biomarkers).

Approximately 40-50% of sepsis cases are considered culture negative. Biomarkers have been studied in the context of sepsis prediction, sepsis diagnosis, assessment of sepsis response to therapy, and biomarker-guided antibiotic therapy. Furthermore, sepsis biomarkers can be divided into prognostic, predictive and theranostic, that is, to guide the choice, dose and duration of therapy ( Fig. 1 ).

The aim of this review is to inform clinicians about biomarkers of infection or sepsis and provide guidance on their use, namely pathogen-specific biomarkers and two host response biomarkers, PCT and CRP.

How to use biomarkers?

When sepsis is suspected, the clinician has several questions to address:

1) What is the probability of infection?

2) What is the severity of the disease and the risk of developing septic shock?

3) What are the most likely pathogens?

4) What is the most appropriate antimicrobial treatment?

5) Is the patient improving or not, and if not, why?

6) When can antimicrobials be stopped?

Doctors often try to answer these questions with the help of biomarkers, but it is important to recognize that their performance in the management of sepsis is suboptimal.

Pathogen-specific and host response biomarkers

Biomarkers are described as a biological characteristic, objectively measured and used as a surrogate record of a physiological or pathological process, or as an indicator of the activity of a drug. In the present context, biomarkers of infection and sepsis could be considered as indicators of infection or dysregulated host response or response to treatment.

Pathogen-specific biomarkers

Although detection of microbial nucleic acids is becoming more common, its place in the management of infections in general, and in bacterial infections specifically, remains uncertain and not yet well standardized. Pathogen-specific biomarkers, such as direct antigen testing, are already widely used in critically ill patients.

Most antigen-based rapid tests are based on immunochromatographic assays and have potential for bedside use. Respiratory antigen tests for Influenza and SARS-CoV-2, and urinary antigen tests for Streptococcus pneumoniae and Legionella spp. They are used in community acquired pneumonia (CAP). They have high specificity but low to moderate sensitivity.

Legionella antigen tests detect Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1. Although this is the predominant cause of legionellosis, false negatives occur with other serogroups or species.

Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) can be diagnosed in symptomatic patients, using a two-step algorithm with rapid enzyme immunoassays to analyze stool samples for both glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) and free toxins A and B. Low positive predictive values at a low CDI prevalence should prevent the test from being used alone. The GDH test is very sensitive and, if positive, is combined with the more specific toxin A/B test.

Fungal antigen assays target structural polysaccharides derived from fungal cell walls. (1,3)-β-D-glucan (BDG) is a pan-fungal serum biomarker commonly used to detect invasive candidiasis. With high sensitivity, but low specificity, BDG is a valuable tool to rule out invasive candidiasis in low-prevalence intensive care units (ICUs).

However, a recent randomized clinical trial (RCT) failed to demonstrate survival benefits of early initiation of BDG-guided antifungal therapy in critically ill septic patients at low to intermediate risk of invasive candidiasis, and at the cost of substantial overuse. of antifungals.

Galactomannan (GM) can be measured in serum and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples and shows high specificity for the diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA). Of note, the BAL fluid GM test is more sensitive than the serum test for diagnosing IPA in non-neutropenic patients, and this test plays a central role in the diagnostic criteria for IPA among the critically ill.

Figure 1. The three vectors of the approach to sepsis: systemic manifestations, organic dysfunction and microbiological documentation (see text). Biomarkers could provide additional information on systemic manifestations of the vector (host response biomarkers, e.g., C-reactive protein-CRP and procalcitonin-PCT), organ dysfunction (e.g., kidney injury biomarkers), and microbiological documentation (pathogen-specific biomarkers). Biomarkers can be classified as prognostic, predictive and theranostic.

Host response biomarkers

In the next section, we analyze two biomarkers of host response, PCT and CRP.

PROCALCITONIN

Procalcitonin is a prohormone precursor to calcitonin. PCT is produced by almost all organs and macrophages, and its levels begin to increase 3–4 h after an inflammatory stimulus, reaching a peak around 24 h.

Prediction of sepsis : PCT is the most studied biomarker in the context of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP). Studies of PCT kinetics in critically ill patients showed poor diagnostic accuracy and low impact regarding guidance for initiation of therapy. Therefore, although associated with decreased antibiotic use in selected settings, the utility of PCT in predicting sepsis in the ICU is limited.

Diagnosis of sepsis : Published studies did not report the cut-off value or used values ranging from 0.5 to 2 μg/L. Although PCT may be superior to CRP in patients with suspected sepsis, PCT should not be used to guide antimicrobial prescribing. Similarly, they do not recommend the use of PCT for the diagnosis of VAP.

Evaluation of the response of sepsis to therapy: in patients with VAP, PCT measured at baseline and on D4 of treatment could predict survival, differentiating patients with good and poor outcomes. In clinical practice, patients who present with persistently elevated D3/D4 biomarker levels of antibiotic therapy should raise suspicion of treatment failure and should prompt aggressive diagnosis and treatment. However, caution should be taken when using biomarkers as an independent criterion to decide when to escalate the diagnosis.

PCT-guided antibiotic therapy: An increasingly popular approach is to use biomarkers to personalize the duration of antibiotic treatment. This approach includes the individual patient’s response to therapy, matching antibiotic discontinuation to the patient’s actual clinical course.

To date, there is strong evidence evaluating PCT-guided antibiotic therapy in critically ill patients confirming that this strategy is safe, is associated with a shorter duration of therapy and, in some RCTs, reduces mortality. However, the main criticisms were that, in the controls of the first trials, the duration of antibiotic therapy was longer than recommended.

C-REACTIVE PROTEIN

Serum CRP is an acute phase protein synthesized exclusively in the liver in response to cytokines. Its levels begin to increase 4-6 hours after an inflammatory stimulus and are not influenced by immunosuppression (steroids or neutropenia) or renal failure. or renal replacement therapy, and does not differ significantly between individuals with or without cirrhosis.

Sepsis prediction : A similar finding was observed in a large study of community-acquired bloodstream infections (BSI) in which the CRP concentration began to increase during the three days before a definitive diagnosis.

Diagnosis of sepsis: the value of a single CRP determination in patients with suspected sepsis has not been consistently demonstrated. However, in a recent prospective observational study, the CAPTAIN study, which evaluated the performance of 53 biomarkers in discriminating between sepsis and non-septic systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), it was found that no biomarker or combination performed better than CRP. alone, and better than PCT.

Evaluation of the response of sepsis to therapy: the use of relative variations of CRP (CRP-ratio), the ratio of the CRP concentration of each day in relation to the level on day 0 (D0), was most informative than the absolute changes of CRP. A strong decrease in CRP index is a surrogate marker of sepsis resolution, while a persistently elevated or increasing CRP index suggests that sepsis is refractory to therapy.

PCR-guided antibiotic therapy: the number of RCTs evaluating the PCR-guided strategy is limited, specifically in ICU patients. Observational and randomized studies have found that the strategy guided by CRP compared to that guided by PCT or fixed duration (short course) did not present substantial differences in the ability to reflect improvement (or worsening) in the clinical course of sepsis and shock. septic and in reducing exposure to antibiotics

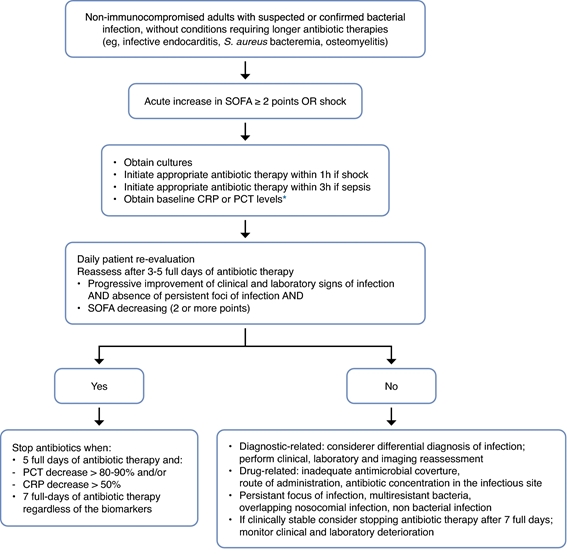

Individualized therapy would be to combine fixed duration with biomarker guidance, using a “double trigger” strategy. After a few days of therapy, antibiotics could be discontinued according to the clinical course and decreases in biomarker levels (CRP or PCT), according to a predefined algorithm, or completion of 5 to 7 full days of therapy with antibiotics, whichever comes first ( Fig.2 ). This individualized strategy has been evaluated in several RCTs showing that biomarker guidance can safely decrease the duration of therapy compared to fixed duration.

Figure 2. User guide for biomarker-guided antibiotic therapy. The initiation of antibiotics in critically ill patients with suspected sepsis should be done regardless of the level of any biomarker. But this must be reevaluated daily. Use the clinical course, course of organ dysfunction (with SOFA score), biomarker kinetics, and duration of antibiotic therapy to determine the optimal duration of therapy. These recommendations do not apply to immunocompromised patients or patients with infections requiring long-term antibiotic therapy, such as endocarditis or osteomyelitis.

Future perspectives

Combining multiple biomarkers to construct a diagnostic panel has not been shown to be consistently superior to any individual biomarker in the diagnosis of sepsis. This arises from the fact that sepsis biomarkers are often highly correlated and therefore diagnostic accuracy has not improved when these assays have been combined.

The diagnostic accuracy of a panel of biomarkers further depends on how the results of individual assays are weighted and how many must be positive for the overall panel to indicate the presence of sepsis. For example, a biomarker panel may be relatively sensitive (requiring only one individual assay to be “positive”) or relatively specific (requiring all individual assays to be positive) depending on how the panel is interpreted.

However, algorithms that combine biomarkers with clinical data have shown promise in identifying patients with sepsis in the ED. One such algorithm combining clinical variables and a panel of biomarkers claimed a negative predictive value of 100% and a positive predictive value of 93% in a cohort of 158 patients.

Conclusions Moving from where we currently are with sepsis biomarkers to a point where we have clinically useful markers that drive patient treatment pathways to improve outcomes will require a significant shift in approach. Unidimensional studies from a single center are unlikely to bring much progress. What is needed are large multicenter cohort studies that use state-of-the-art algorithms to identify biomarkers that predict differential responses to interventions in specific clinical endotypes. Combining existing tools in multicenter and multidisciplinary collaborations will be the most effective way to discover new biomarkers that can be implemented in clinical practice to optimize patient care. Until then, sepsis biomarkers may be useful complementary tools when clinicians need additional information to optimize patient care at the bedside. Serial determinations are more informative than a single value and biomarkers should never be used as a stand-alone test, but always in conjunction with a thorough clinical evaluation. |