Filopodia are a structural substrate for silent synapses in the adult neocortex. Summary Newly generated excitatory synapses in the mammalian cortex lack sufficient AMPA-type glutamate receptors to mediate neurotransmission, resulting in functionally silent synapses that require activity-dependent plasticity to mature. Silent synapses are abundant in early development, during which they mediate circuit formation and refinement, but are thought to be rare in adulthood1. However, adults retain a capacity for neuronal plasticity and flexible learning that suggests that the formation of new connections still prevails. Here we use super-resolution protein imaging to visualize synaptic proteins at 2,234 layer 5 pyramidal neuron synapses in the primary visual cortex of adult mice. Unexpectedly, about 25% of these synapses lack AMPA receptors. These putative silent synapses were located at the tips of thin dendritic protrusions, known as filopodia, which were an order of magnitude more abundant than previously thought (comprising approximately 30% of all dendritic protrusions). Physiological experiments revealed that filopodia indeed lack AMPA receptor-mediated transmission, but exhibit NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission. Furthermore, we demonstrate that functionally silent synapses in filopodia can be silenced through Hebbian plasticity, recruiting new active connections into the input array of a neuron. These results challenge the model that functional connectivity is largely fixed in the adult cortex and demonstrate a new mechanism for flexible control of synaptic wiring that expands the learning capabilities of the mature brain. |

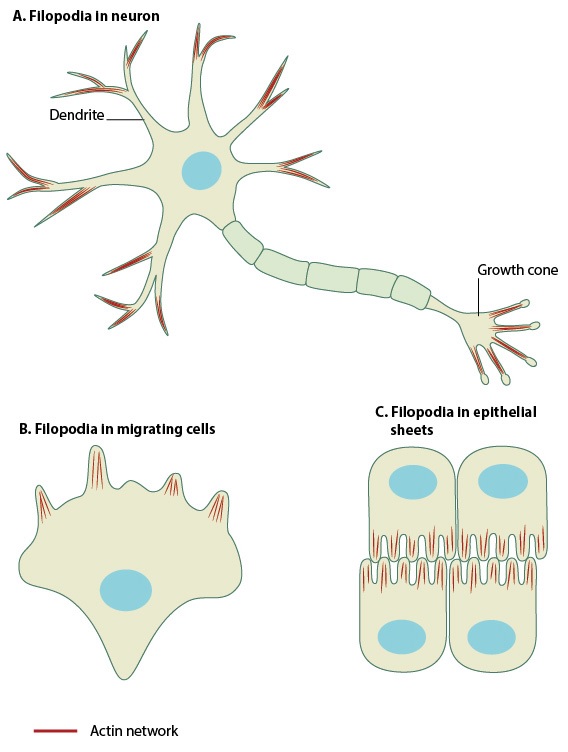

Filopodia (singular filopodium) are thin membrane protrusions that act as antennas for a cell to probe the surrounding environment. The non-protruding filopodia are mechanically related to the microspikes. Filopodia are commonly found embedded in or protruding from the lamelliopodium at the free front of migrating tissue sheets. Filopodia are also prominent in neurite growth cones and in individual cells such as fibroblasts.

Comments

MIT neuroscientists have discovered that the adult brain contains millions of "silent synapses," immature connections between neurons that remain dormant until they are recruited to help form new memories.

Until now, silent synapses were believed to be present only during early development, when they help the brain learn the new information it is exposed to in the first years of life. However, the new MIT study revealed that in adult mice, about 30 percent of all synapses in the cerebral cortex are silent.

The existence of these silent synapses may help explain how the adult brain can continually form new memories and learn new things without having to modify existing conventional synapses, the researchers say.

"These silent synapses look for new connections, and when important new information is presented, the connections between the relevant neurons are strengthened. This allows the brain to create new memories without overwriting important memories stored in mature synapses , which are more difficult to change. " says Dimitra Vardalaki, an MIT graduate student and lead author of the new study.

Mark Harnett, associate professor of brain and cognitive sciences, is the senior author of the paper published in Nature . Kwanghun Chung, associate professor of chemical engineering at MIT, is also an author.

A surprising discovery

When scientists first discovered silent synapses decades ago, they were primarily observed in the brains of young mice and other animals. During early development, these synapses are thought to help the brain acquire the enormous amount of information that babies need to learn about their environment and how to interact with it. In mice, these synapses were believed to disappear around 12 days of age (equivalent to the first months of human life).

However, some neuroscientists have proposed that silent synapses may persist into adulthood and assist in the formation of new memories. Evidence for this has been seen in animal models of addiction where it is believed to be largely an aberrant learning disorder.

Theoretical work in the field by Stefano Fusi and Larry Abbott of Columbia University has also proposed that neurons must show a wide range of different plasticity mechanisms to explain how brains can efficiently learn new things and retain them in memory. long-term. In this scenario, some synapses must be easily established or modified to form new memories, while others must remain much more stable to preserve long-term memories.

In the new study, the MIT team did not specifically set out to look for silent synapses. Instead, they were following up on an intriguing finding from an earlier study in Harnett’s lab. In that paper, the researchers showed that within a single neuron, dendrites, antenna-like extensions that protrude from neurons, can process synaptic input in different ways, depending on their location.

As part of that study, the researchers attempted to measure neurotransmitter receptors on different dendritic branches, to see if that would help explain the differences in their behavior. To do that, they used a technique called eMAP developed by Chung. With this technique, researchers can physically expand a tissue sample and then label specific proteins in the sample, making super-high-resolution imaging possible.

While making that image, they made a surprising discovery. "The first thing we saw, which was super strange and we weren’t expecting, was that there were filopodia everywhere," Harnett says.

Filopodia, thin membrane protrusions that extend from dendrites, have been seen before, but neuroscientists didn’t know exactly what they did. That’s partly because filopodia are so small that they are difficult to see with traditional imaging techniques.

After making this observation, the MIT team set out to try to find filopodia in other parts of the adult brain, using the eMAP technique. To their surprise, they found filopodia in the mouse’s visual cortex and other parts of the brain, at a level 10 times higher than previously seen. They also found that filopodia had neurotransmitter receptors called NMDA receptors , but not AMPA receptors.

A typical active synapse has both types of receptors, which bind to the neurotransmitter glutamate. NMDA receptors normally require cooperation with AMPA receptors to transmit signals because magnesium ions block NMDA receptors at the normal resting potential of neurons. Therefore, when AMPA receptors are not present, synapses that have only NMDA receptors cannot pass an electrical current and are called "silent" .

Unsilenced synapses

To investigate whether these filopodia could be silent synapses, the researchers used a modified version of an experimental technique known as patch clamping . This allowed them to monitor the electrical activity generated in individual filopodia while attempting to stimulate them by mimicking the release of the neurotransmitter glutamate from a neighboring neuron.

Using this technique, the researchers found that glutamate would not generate any electrical signal in the filopodium receiving the input, unless the NMDA receptors were experimentally unlocked. This offers strong support for the theory that filopodia represent silent synapses within the brain, the researchers say.

The researchers also showed that they could "unsilence" these synapses by combining the release of glutamate with an electrical current coming from the body of the neuron. This combined stimulation leads to the accumulation of AMPA receptors at the silent synapse, allowing it to form a strong connection with the nearby axon that releases glutamate.

The researchers found that converting silent synapses into active synapses was much easier than altering mature synapses.

"If you start with an already functional synapse, that plasticity protocol doesn’t work," Harnett says. "Synapses in the adult brain have a much higher threshold, presumably because you want those memories to be quite resilient. You don’t want them to be constantly overwritten. Filopodia, on the other hand, can be captured to form new memories."

"Flexible and robust"

The findings offer support for the theory proposed by Abbott and Fusi that the adult brain includes highly plastic synapses that can be recruited to form new memories , the researchers say.

"This paper is, to my knowledge, the first real evidence that this is how it actually works in the mammalian brain," Harnett says. "Filopodia allows a memory system to be both flexible and robust. Flexibility is needed to acquire new information, but stability is also needed to retain important information."

Researchers are now looking for evidence of these silent synapses in human brain tissue. They also hope to study whether the number or function of these synapses is affected by factors such as aging or neurodegenerative diseases.

"It’s quite possible that by changing the flexibility you have in a memory system, it could become much more difficult to change your behaviors and habits or incorporate new information," Harnett says. "You could also imagine finding some of the molecular players that are involved in filopodia and trying to manipulate some of those things to try to restore flexible memory as we age."

The research was funded by the Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds, the National Institutes of Health, the James W. and Patricia T. Poitras Fund at MIT, a Klingenstein-Simons Fellowship, a Vallee Foundation Grant, and a McKnight Fellowship.