Highlights

|

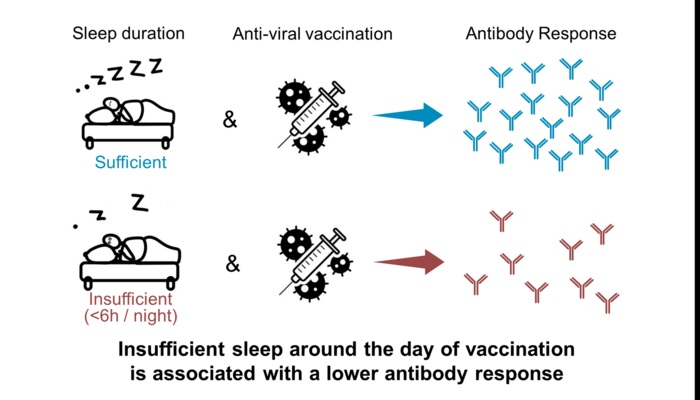

A meta-analysis of associations between insufficient sleep duration and antibody response to vaccination

Summary

Vaccination is an important strategy to control a viral pandemic. Simple behavioral interventions that can boost vaccine responses have not yet been identified. We performed meta-analysis to summarize the evidence linking the amount of sleep obtained in the days surrounding vaccination to antibody response in healthy adults. The authors of the included studies provided the information necessary to accurately estimate the pooled effect size (ES) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and to examine differences by sex.

Credits: Spiegel et al.

Comments

The association between self-reported short sleep (<6 h/night) and reduced vaccine response did not meet our predefined statistical significance criteria (total n = 504, ages 18–85; overall ES [95% CI] = 0. 29 [−0.04, 0.63]). Objectively assessed short sleep was associated with a strong decrease in antibody response (total n = 304, ages 18–60; overall ES [95% CI] = 0.79 [0.40, 1.18]). In men, the pooled ES was large (overall ES [95% CI] = 0.93 [0.54, 1.33]), while it did not reach significance in women (overall ES [95% CI] = 0.42 [−0.49, 1.32]).

These results provide evidence that insufficient sleep duration substantially decreases the response to antiviral vaccination and suggest that achieving an adequate amount of sleep during the days surrounding vaccination may enhance and prolong the humoral response. Large-scale, well-controlled studies are urgently needed to define (1) the time window around inoculation when optimization of sleep duration is most beneficial, (2) the causes of the sex disparity in sleep impact in the response, and (3) the amount of sleep needed to protect the response.

We all know how important sleep is for mental health, but a meta-analysis published in the journal Current Biology found that good sleep also helps our immune system respond to vaccination. The authors found that people who slept less than six hours a night produced significantly fewer antibodies than people who slept seven hours or more, and the shortfall was equivalent to two months of antibody decline.

"Sleeping well not only amplifies but may also extend the duration of vaccine protection," says lead author Eve Van Cauter, a professor emeritus at the University of Chicago who, along with lead author Karine Spiegel of the French National Institute of Health and Medicine, published a landmark study on the effects of sleep on vaccination in 2002.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit and mass vaccination became an international priority, Spiegel and Van Cauter set out to summarize our current knowledge about the effect of sleep duration on vaccine response.

To do this, they reviewed the literature and then combined and reanalyzed the results of seven studies that vaccinated against viral infections (influenza and hepatitis A and B). In their analysis, the team compared the antibody response of people who got a "normal" amount of sleep (7 to 9 hours, according to the National Sleep Foundation’s recommendation for healthy adults) with those of people who got less than 6 hours per night. They compared the effect for men versus women and adults over 65 versus younger adults.

Overall, they found strong evidence that sleeping less than 6 hours a night reduces the immune response to vaccination.

However, when they analyzed men and women separately, the result was only significant in men, and the effect of sleep duration on antibody production was much more variable in women. This difference is likely due to fluctuating sex hormone levels in women, the authors say.

“We know from immunological studies that sex hormones influence the immune system,” says Spiegel. “In women, immunity is influenced by menstrual cycle status, contraceptive use, and menopause and postmenopausal status, but unfortunately, none of the studies we summarized had data on sex hormone levels.”

The negative effect of insufficient sleep on antibody levels was also greater for adults ages 18 to 60 compared to people ages 65 and older. This was not surprising because older adults tend to sleep less overall; Going from seven hours of sleep a night to less than six hours is not as big a change as going from eight hours to less than six a night.

Some of the studies measured sleep duration directly, either through motion-sensing wristwatches or in a sleep lab, while others relied on self-reported sleep duration. In both cases, short sleep duration was associated with lower antibody levels, but the effect was stronger in studies that used objective measures of sleep, probably because people are notoriously bad at estimating how much sleep they’ve had. .

Knowing that sleep duration affects vaccination could give people some degree of control over their immunity, the authors say. “When you look at the variability in the protection provided by the COVID-19 vaccines, people who have pre-existing conditions are less protected, men are less protected than women, and obese people are less protected than people who are not obese. Those are all factors that an individual person has no control over, but can modify their sleep,” says Van Cauter.

However, there is much more to know about sleep and vaccination, the authors say. “We need to understand sex differences, which days around the time of vaccination are most important, and exactly how much sleep is needed so we can guide people,” Spiegel says. “We are going to vaccinate millions and millions of people in the coming years, and this is one aspect that can help maximize protection.”