Association between daily alcohol intake and risk of all-cause mortality Key points What is the association between average daily alcohol intake and all-cause mortality? Findings This systematic review and meta-analysis of 107 cohort studies including more than 4.8 million participants found no significant reductions in the risk of all-cause mortality for drinkers who drank less than 25 g of ethanol per day (about 2 Canadian standard beverages compared to lifetime consumption of non-drinkers) after adjusting for key study characteristics such as the median age and sex of the study cohorts. There was a significantly increased risk of all-cause mortality among female drinkers who drank 25 or more grams per day and among male drinkers who drank 45 or more grams per day.

|

Importance

A previous meta-analysis of the association between alcohol consumption and all-cause mortality found no statistically significant reductions in mortality risk with low levels of consumption compared with lifetime non-drinkers. However, risk estimates may have been affected by the number and quality of studies available at the time, especially those for women and younger cohorts.

Aim

To investigate the association between alcohol consumption and all-cause mortality, and how sources of bias may change the results.

Data sources

A systematic search was conducted in PubMed and Web of Science to identify studies published between January 1980 and July 2021.

Study selection

Cohort studies were identified through a systematic review to facilitate comparisons of studies with and without some degree of control for biases affecting distinctions between abstainers and drinkers. The review identified 107 studies on alcohol consumption and all-cause mortality published from 1980 to July 2021.

Data extraction and synthesis

Linear mixed regression models were used to model relative risks, first pooled for all studies and then stratified by cohort median age (<56 vs ≥56 years) and sex (male vs female). Data was analyzed from September 2021 to August 2022.

Main results and measures

Relative risk estimates for the association between mean daily alcohol intake and all-cause mortality.

Results

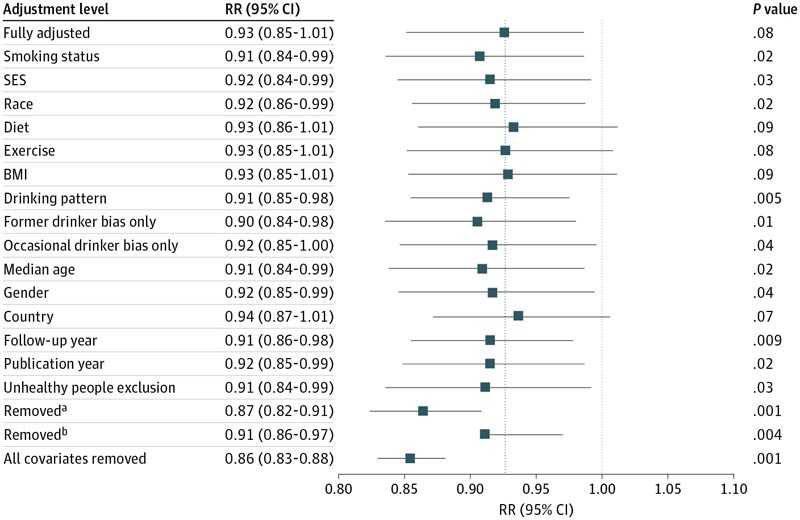

There were 724 risk estimates for all-cause mortality due to alcohol consumption from the 107 cohort studies (4838825 participants and 425564 deaths available) for analysis. In models adjusting for the potential confounding effects of sampling variation, ex-drinker bias, and other prespecified study-level quality criteria, meta-analysis of the 107 included studies found no significant reduction in mortality risk. for all causes among occasional patients (>0 to <1.3 g of ethanol per day, relative risk [RR], 0.96; 95% CI, 0.86-1.06; P = .41) or low-volume drinkers (1.3-24.0 g per day; RR, 0.93; P = .07) compared with lifetime non-drinkers.

In the fully adjusted model, there was a nonsignificant increased risk of all-cause mortality among drinkers drinking 25 to 44 g per day (RR, 1.05; P = 0.28) and a significantly increased risk for drinkers who drank 45 to 64 and 65 or more grams per day (RR 1.19 and 1.35; p < 0.001).

There were significantly higher risks of mortality among female drinkers compared with female non-drinkers throughout their life (RR, 1.22; P = 0.03).

Figure . Relative risk (RR) of all-cause mortality due to low-volume alcohol consumption (1.3-24.0 g ethanol per day) with and without adjustment for potential confounding by each covariate or set of covariates

Conclusions and relevance

In this updated systematic review and meta-analysis, low or moderate daily alcohol intake was not significantly associated with the risk of all-cause mortality, while increased risk was evident at higher levels of consumption, starting at lower levels. for women than for men.

Comments

Dozens of studies have reportedly shown that a glass of wine or a mug of beer a day could reduce the risk of heart disease and death.

But these studies are flawed , a new evidence review says, and the potential health benefits of moderate alcohol consumption fade when those flaws and biases are taken into account .

At best, a drink or two a day has no good or bad effect on a person’s health, while three or more drinks a day significantly increase the risk of premature death, researchers report.

"Drinking at low or moderate levels is defined roughly between one drink a week and two drinks a day. That’s the amount of alcohol that many studies, if you look at them uncritically, suggest reduces the risk of dying prematurely," said the co-investigator Tim Stockwell . He is former director of the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research at the University of Victoria in British Columbia.

But after adjusting for the study’s flaws and biases, "the appearance of benefit from moderate alcohol consumption greatly diminishes and, in some cases, disappears entirely," Stockwell said.

A standard drink in the United States contains about 14 grams of pure alcohol, according to the U.S. National Institutes of Health. That’s equivalent to about 12 ounces of beer, 5 ounces of wine, or 1.5 ounces of distilled spirits.

For this analysis, Stockwell and his colleagues evaluated 107 studies that evaluated the relationship between alcohol consumption and death. These studies included almost 5 million participants from several countries.

"This is an overview of a lot of really bad studies," Stockwell said. "There are many confounding and bias factors in these studies, and our analysis illustrates this."

Ex-drinkers are not lifelong abstainers

For example, many studies tend to put former drinkers in the same group as lifelong abstainers, referring to all of them as "non-drinkers," Stockwell said.

But former drinkers have usually stopped or reduced alcohol consumption because of health problems, Stockwell said. The new analysis found that former drinkers actually have a 22% higher risk of death compared to abstainers. Their presence in the "non-drinking" group skews the results, creating the illusion that light daily drinking is healthy, Stockwell said.

For the new study, researchers combined the data and then made adjustments that accounted for problems such as "ex-drinker bias . " "We’ve put patches on all of these bad studies to try to explore how these different characteristics result in the emergence of health benefits," Stockwell said.

The combined adjusted data from the studies showed that neither light drinkers (less than 1.3 grams of alcohol, or one drink every two weeks) nor light drinkers (up to 24 grams a day, or almost two drinks) had a significantly reduced risk of death.

The researchers found a slight, but not significant, increased risk of death among those who drank 25 to 44 grams a day, about three drinks. And there was a significantly higher risk of death for people who drank 45 or more grams of alcohol a day, the results showed.

The highest risk was among people who drank 65 grams of alcohol or more a day, or more than four drinks. Their risk of death was 35% higher than that of occasional drinkers.

"There’s this question about whether low-level alcohol consumption is beneficial, and I think I would interpret this to mean that it’s actually not particularly beneficial," said Catherine Lesko , assistant professor of epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, in baltimore "I don’t know if it’s harmful to drink at very low levels. But many of the results are reinforcing the harmful effects of even moderate to high alcohol consumption." The analysis also found that alcohol has a more dramatic effect in lower quantities on women’s risk of death.

Women’s increased risk of death from drinking was consistently higher than men’s risk.

For example, the highest risk of death for women who drink 65 grams or more a day was 61 percent, almost double that of men who drink that amount.

"Women experience alcohol differently than men due to biological factors. Even when drinking the same amount of alcohol, women will have higher blood alcohol levels, feel intoxicated faster, and take longer to metabolize alcohol," noted Pat Aussem . She is associate vice president of consumer clinical content development for the Partnership to End Addiction.

These results make sense given that alcohol consumption has been linked to at least 22 specific causes of death, Stockwell said.

Alcohol consumption increases the risk of liver disease, some cancers, stroke and heart disease, Stockwell said. It also contributes to deaths from accident injuries, car crashes, homicides, and suicides.

Other studies that take genetics into account "confirm our conclusion that people who drink moderately are not protected against heart disease or premature death. So our results are consistent with other studies that use a stronger design," he said. Stockwell.

Risk continuity

Aussem said research has established a "risk continuum" associated with weekly alcohol consumption, where the risk of harm is:

- 2 standard drinks or less per week: You are likely to avoid alcohol-related consequences for yourself or others at this level.

- 3 to 6 standard drinks a week: Your risk of developing several types of cancer, including breast and colon cancer, increases at this level.

- 7 standard drinks or more a week: Your risk of heart disease or stroke increases significantly at this level.

"Each additional standard drink radically increases the risk of alcohol-related consequences. These risks increase in tandem with consumption, as it is more difficult to repair damage caused to cellular tissue in the body and brain," Aussem said.

"Simply put, less is better ," he added. "Any steps to reduce can be helpful in terms of reducing the risks of alcohol-related cancers and cardiovascular diseases."

The researchers pointed out some limitations of their work. Measurement of alcohol consumption was imperfect in most studies, they said, and self-reported alcohol consumption was probably underreported in many cases. To more accurately assess the risks of alcohol, future studies should look at specific diseases related to alcohol consumption and link them to specific groups, Stockwell said. For example, studies could examine the cancer risk that alcohol poses for men versus women.

Studies would also do better to use occasional drinkers as a reference group, because they tend to have more "normal" health characteristics than abstainers, the researchers concluded.

Experts say the less alcohol a person drinks, the better for their health.

Key takeaways

|

The new evidence review was published in JAMA Network Open .