Dopamine facilitates the translation of physical effort into effort evaluations Summary Our evaluations of effort are critically shaped by experiences of effort. However, it is unclear how the nervous system transforms physical effort into effort evaluations. The availability of the neuromodulator dopamine influences the characteristics of motor performance and effort-based decision making. To evaluate the role of dopamine in the translation of effort into work evaluations, we had participants with Parkinson’s disease , in states of dopamine depletion (without dopaminergic medication) and elevated (with dopaminergic medication), exert levels of physical effort and evaluate retrospectively how much effort they exerted. In a dopamine-depleted state , participants exhibited greater effort variability and overreported their effort levels, compared to the dopamine-supplemented state . Increased effort variability was associated with less accurate effort assessment, and dopamine had a protective influence on this effect, reducing the degree to which effort variability corrupted effort assessments. Our findings provide an insight into the role of dopamine in translating motor performance characteristics into judgments of effort, and a potential therapeutic target for the increased sense of effort observed in a variety of neurological and psychiatric conditions. |

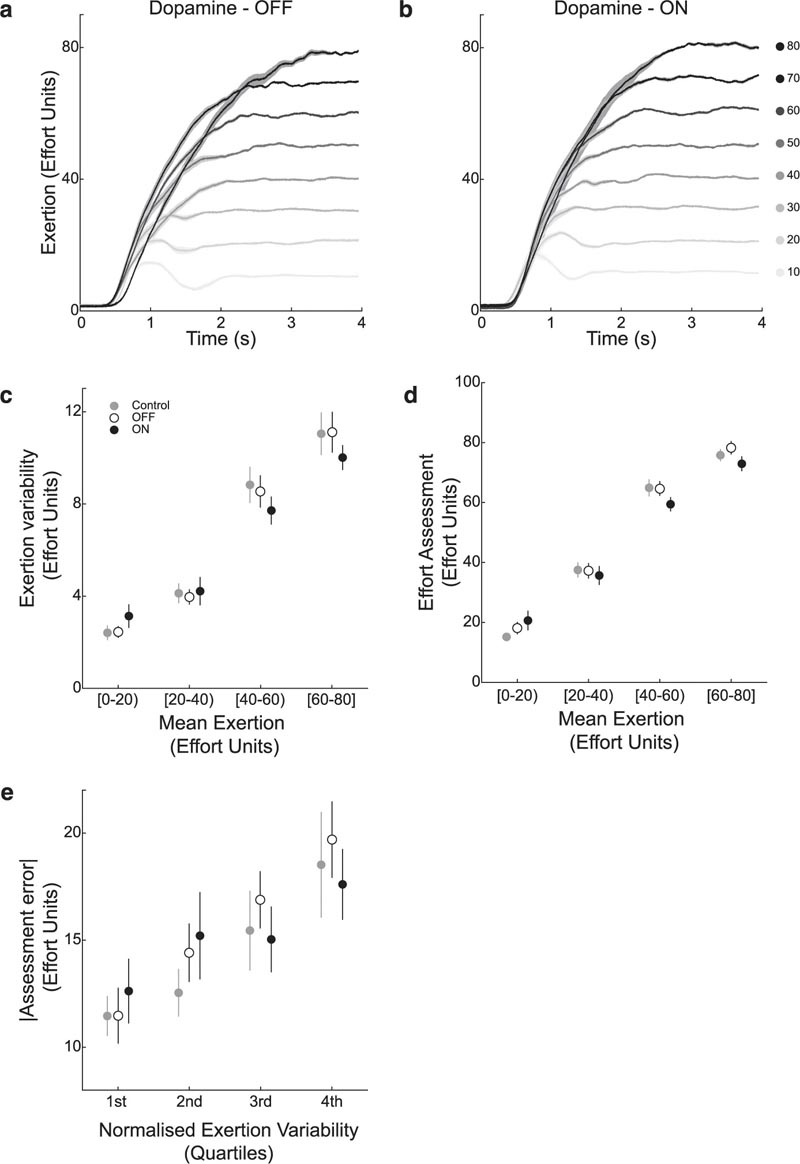

Figure : Average effort profiles, during the evaluation phase, for a representative participant in the conditions a Dopamine OFF and b ON. All effort levels are presented in units of effort, which were relative to the participants’ maximum effort. In both conditions, participants were able to exert themselves to the target level and endure. The plots in Panels c–e were used for illustrative purposes and not for statistical inference, which was performed using linear mixed-effects models. (Control group: gray circles; dopamine OFF state: open circles; ON state: black circles). c Effort variability as a function of the average effort during the evaluation phase. Effort variability was calculated as the standard deviation of the last 3 s of effort production. For illustrative purposes, effort variability was combined into mean effort intervals of 20 effort units. There, the error bars represent the standard error of the mean. When participants were in the dopamine ON condition, they exhibited less of an increase in effort variability as effort increased, compared to OFF. The behavior of the control group matched the participants in the OFF condition. d Effort assessment based on the average effort during the assessment phase. Mean effort was calculated as the average of the last 3 s of effort production. For illustrative purposes, effort assessments were grouped into mean effort intervals of 20 effort units. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Increasing dopamine availability had a moderating effect on increases in effort ratings with exercise. The control group’s behavior matched participants in the OFF condition, and evaluations were lower in the ON condition of dopamine compared to controls. e Judgment errors increase with normalized effort variability and this increase is more pronounced in the dopamine OFF condition, compared to dopamine ON. For each trial, an evaluation error metric was calculated by taking the difference between the evaluated effort and the average effort. A normalized effort variability value was calculated by dividing effort variability by mean effort, allowing performance to be evaluated during different levels of effort in a unified model. For illustration, assessment errors and normalized effort variability were grouped into quartiles of normalized effort variability. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Increasing effort variability disrupted participants’ effort appraisals, and increasing dopamine availability had a protective effect on the propensity for effort variability to disrupt effort appraisal. The behavior of the control group was not significantly different from the behavior in the ON and OFF conditions.

Comments

Dopamine , a brain chemical long associated with pleasure, motivation, and reward-seeking, also appears to play an important role in why exercise and other physical endeavors feel ’ easy ’ for some people and ’exhausting’. ” for others, according to the results of a study of people with Parkinson’s disease. Parkinson’s disease is characterized by a loss of dopamine-producing cells in the brain over time.

The findings, published in NPG Parkinson’s Disease , could, researchers say, eventually lead to more effective ways to help people establish and maintain exercise regimens, new treatments for fatigue associated with depression and many other conditions, and a better understanding of Parkinson’s disease.

"Researchers have long tried to understand why some people find physical exertion easier than others," says study leader Vikram Chib, Ph.D., associate professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and research scientist at the Kennedy Krieger Institute. "The results of this study suggest that the amount of dopamine available in the brain is a key factor ."

Chib explains that after a session of physical activity, people’s perception and self-reports of effort exerted vary, and also guide their decisions about undertaking future efforts. Previous studies have shown that people with increased dopamine are more willing to exert physical effort in exchange for rewards, but the current study focuses on the role of dopamine in self-assessment of the effort required for a physical task, without the promise of a reward.

For the study, Chib and his colleagues at Johns Hopkins Medicine and the Kennedy Krieger Institute recruited 19 adults diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, a condition in which neurons in the brain that produce dopamine gradually die, causing involuntary, uncontrollable movements. , such as tremors, fatigue, stiffness, and problems with balance or coordination.

In Chib’s lab, 10 male volunteers and nine female volunteers with an average age of 67 were asked to perform the same physical task (squeezing a handle equipped with a sensor) on two different days four weeks apart. On one of the days, patients were asked to take their standard daily synthetic dopamine medication as they normally would. On the other hand, they were asked not to take their medication for at least 12 hours before performing the compression test.

On both days, patients were initially taught to squeeze a grip sensor at various levels of defined effort, and then were asked to squeeze and report how many units of effort they performed.

When participants had taken their usual synthetic dopamine medication, their self-ratings of units of effort performed were more accurate than when they had not taken the drug. They also had less variability in their efforts, showing accurate grips when the researchers instructed them to squeeze at different effort levels.

In contrast, when patients had not taken the medication , they consistently overreported their efforts, meaning they perceived the task to be physically more difficult, and had significantly greater variability between grasps after being cued.

In another experiment, patients were given the choice between a safe option of squeezing with a relatively low amount of effort on the grip sensor or flipping a coin and risking having to exert no or very little effort. high effort. When these volunteers had taken their medication, they were more willing to take the risk of having to exert more effort than when they were not taking their medication.

A third experiment offered participants the option of getting a small guaranteed amount of money or, with the flip of a coin, getting nothing or a larger amount of money. The results showed no differences in the subjects on the days they took their medication and those they did not. This result, the researchers say, suggests that dopamine’s influence on risk-taking preferences is specific to decision-making based on physical effort.

Together, Chib says, these findings suggest that dopamine level is a critical factor in helping people accurately assess how much effort a physical task requires, which can significantly affect how much effort they are willing to exert for future tasks. For example, if someone perceives that a physical task will require extraordinary effort, they may be less motivated to do it.

Understanding more about the chemistry and biology of motivation could promote ways to motivate exercise and physical therapy regimens, Chib says. Additionally, inefficient dopamine signaling could help explain the widespread fatigue present in conditions such as depression and long COVID, and during cancer treatments. Currently, he and his colleagues are studying the role of dopamine in clinical fatigue.

Other researchers who participated in this study include Purnima Padmanabhan, Agostina Casamento-Moran, and Alexander Pantelyat of Johns Hopkins; Ryan Roemmich of Johns Hopkins and the Kennedy Krieger Institute; and Anthony González of the Kennedy Krieger Institute.

This work was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (R01HD097619), the National Institutes of Mental Health (R56MH113627 and R01MH119086), and the National Institute on Aging (R21AG059184).