The disembodied metaphor: understanding and production of tactile metaphors without somatosensation Summary Introduction : Proposals of embodied metaphors and embodied cognition have suggested that abstract concepts are understood indirectly through the simulation of previous sensory experiences in a different domain. While exceptions have been noted for sensory deficits and impairments that are common, such as vision and hearing, somatosensation (proprioception, haptic touch, pain, pressure, temperature, etc.) is commonly assumed to be critical for understanding. of the sensory production of metaphors and abstract thinking in general. In this way, our past sensory experiences are fundamental to our understanding not only of the world around us, but also our sense of self. This would suggest that Kim, who was born without somatosensation, would have difficulty understanding, using, or even thinking about many abstract concepts typically linked to different sensory experiences through metaphor, including creating a sense of self. Methods: To examine her understanding of sensory metaphors, Kim was asked to select the best sensory idiom given her context. Her friends and family, as well as a representative sample of people online, were recruited to complete the survey as controls. Additionally, we transcribed and analyzed six hours of spontaneous speech to determine whether Kim uses spontaneous somatosensory metaphors appropriately. Results: Results from the idiom survey indicate that Kim performs as well as controls despite lacking prior direct sensory experiences of these concepts. The analysis of spontaneous speech highlights that Kim appropriately uses tactile expressions in their abstract metaphorical and concrete sensory meanings. Discussion: Together, these two studies demonstrate that what is lost in sensory experiences can be recovered in linguistic experiences , since Kim’s understanding of tactile words was acquired in the complete absence of somatosensory experiences. This study demonstrates that people can understand and use tactile language and metaphor without drawing on past somatosensory experiences and therefore challenges a strong definition of embodied cognition that requires sensory simulations in language understanding and abstract thinking. |

Comments

Research with a perhaps unique individual shows that they can understand and use tactile language and metaphors without relying on previous sensory experiences . These findings challenge notions of embodied cognition that insist that language comprehension and abstract thought require direct memory of such sensations.

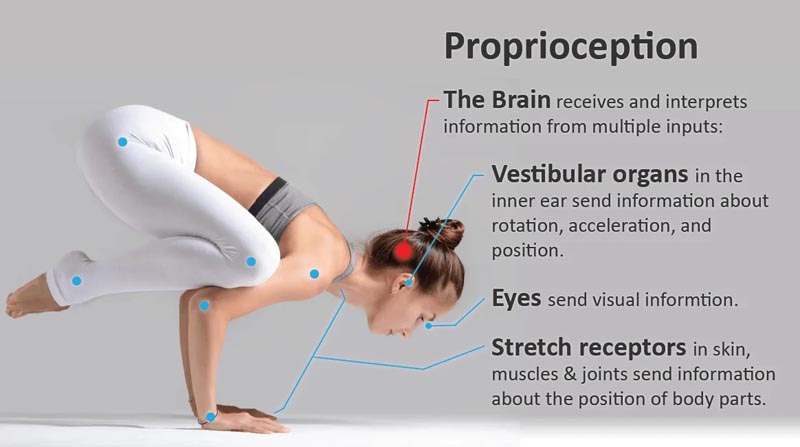

Blind or color-blind people can describe colors and use expressions such as "green with envy" or "feeling blue . " A hearing-impaired person may also say that those same vibrating tones are "loud . " But many linguists and cognitive neuroscientists have assumed that somatosensation (touch, pain, pressure, temperature, and proprioception, or the sense of the body’s orientation in space) is fundamental to understanding metaphors that have to do with tactile sensations. Understanding expressions such as "she’s having a bad time" or "that class was difficult ," it was believed, requires prior experience with those sensations to extend their meaning to metaphors.

Now, research from the University of Chicago with a perhaps unique individual shows that he can understand and use tactile language and metaphors without relying on previous sensory experiences . These findings challenge notions of embodied cognition that insist that language comprehension and abstract thought require direct memory of such sensations.

Life without somatosensation

Since 2014, Peggy Mason, PhD, Professor of Neurobiology, has been working with Kim (who agreed to be identified by her first name), a woman who was born without somatosensation . She has no sensory nerve fibers to sense her body. This includes proprioception , so she cannot walk or stand independently due to difficulty maintaining balance.

Because Kim cannot perceive tactile sensations, she relies on other senses to perceive the world.

For example, to determine the hardness of an object, listen to what kind of sound it makes when you hit it against a surface. He relies on visual cues to determine textures, but because he has never experienced those sensations directly, he has no memories or stored experiences to refer to later when using language and metaphors. However, in a multiple-choice test that asked users to select the best sensory expression to complete a sentence, Kim performed as well as controls.

"Phrases like ’handling a difficult deal’ are extensions of words that have a very sensory root," Mason said. "Since Kim doesn’t have somatosensation, we really wondered how she would deal with this. But we see that while sensory experiences can be very important for many people, they are not necessary. You can learn this too."

To investigate Kim’s language use, Mason, a neurobiologist who studies empathy and other prosocial behaviors, collaborated with two professors in UChicago’s Department of Linguistics: Jacob Phillips, PhD, a humanities teaching fellow, and Lenore Grenoble, PhD, the John Matthews Manly Distinguished Service Professor. Grenoble said Kim provided a unique opportunity because until now, ideas about language and metaphors derived from somatosensation simply could not be tested.

"Kim is a gift in that sense because we can try things with her that we couldn’t possibly try otherwise, because everyone has had something from this experience. Some people have lost it, but they have a memory to draw on," she said. "You just haven’t ever had it and that’s unique. It may be a single case study , but it’s pretty powerful."

Learning by association vs experience

In addition to Kim, the researchers recruited two control groups to perform the test. Thirty-nine native American English speakers were recruited online, and 24 of Kim’s friends and family were recruited to account for possible differences between the use of idiomatic expressions within Kim’s social circle and the average English speaker. The online questionnaire featured 80 questions with short one- or two-sentence vignettes followed by a selection of four idiomatic expressions. For example:

Liza bought her first car and successfully negotiated the price for five thousand dollars. Lisa:

a) He made a difficult deal (correct answer).

b) Made a rough guess.

c) It didn’t hit the target.

d) Go to sleep.

Kim performed as well or better than the control groups, identifying the correct response for almost all examples, including tactile and non-sensory expressions. Grenoble says this marks a milestone in the debate over embodied cognition and metaphor.

"Now we have data to show which side of the debate is right, and that is that you don’t need to have somatosensory experience . That opens doors to really understanding how these things are acquired, how they change, and how they are used for all kinds of things," he said. .

Although Kim passed the multiple-choice exam, the document describes an interaction that gives insight into her experience of the world. The researchers were discussing the word "thick" with Kim and her mother, and Kim said she assumed food must be lumpy because she uses the same root word. Her mother pointed out that cooked grits are definitely not gritty, and Kim responded, "I think quite literally about words, especially words about, you know, the feel and things like that. [...] A lot of times words like we’re talking about ’gritty’ or like ’soft’ or ’hard’ or, like I’m trying to think of examples, like ’coarse.’ My definitions come strictly from what other people have told me, so that’s where I get it from ".

Grenoble said this experience shows that while direct experience helps, the way Kim interprets these expressions may not be much different from how others do. "In fact, I think most people learn it through association, because they are metaphors . They are not literal meanings, so you have to understand how to interpret the metaphor," she said. "What Kim is really showing us is that you’re interpreting him linguistically, because he doesn’t have anything else."

Mason, who has also published research on how Kim and another person who lacks sentience use visual cues to develop a sense of their bodies in space, said he hopes to work with Grenoble and Phillips on more projects about how Kim describes objects and uses gestures.

"Kim has been an incredible participant in the study, on the verge of becoming a co-author on some of these studies," he said. “This has been a flourishing and very enjoyable collaboration with such a unique individual.”

Final message

As this study shows, Kim’s use and understanding of tactile words cannot come from somatosensation; It may depend on the visual interpretation of a surface, but it also depends crucially on linguistically acquired knowledge. Her understanding of the metaphorical use of touch phrases also depends not only on introspection but also on linguistic input. It is not surprising that she can understand and produce tactile words in the language because that is how she has acquired them. Kim is so highly educated and has had such extensive exposure to literary traditions that it would be surprising if the opposite were true.

Separate tests of your lexical knowledge of tactile adjectives show that you can adequately define all the terms provided to you. For words like rough , he can define and use them in both the sensory domain of origin and the metaphorical domain, even if he cannot know for sure whether the physical object in question is rough to the touch. Her linguistic knowledge can only take her so far because she still has gaps in her experiential knowledge, which highlights her different views than her mother’s for a low-frequency word like gritty. .

Kim’s understanding of tactile words in both their concrete origin and their metaphorical meaning complicates the proposal of primary metaphors, by which the target domain is understood through an implicit association with the source domain (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980). . For tactile expressions , the source domain is concrete and experienced directly through touch and the target domain is abstract and experienced through introspection. Therefore, the target domain can only be derived through the source domain . However, for Kim, this cannot be the case since she clearly has no direct sensory experience. For her, the sensory domain is not concrete but as abstract as the objective domain. Therefore, it is not necessary for her to understand abstract concepts as difficult through association with physicality , as it would involve understanding the abstract through the abstract . This raises the question of whether a tactile metaphor like "I had a rough day" is even a Kim metaphor rather than simply a separate lexical entry for a word like "rough . " What does Kim gain by understanding the abstract through the abstract? Does Kim use sensory metaphors that she has no direct experience with simply because of their standardization and frequency in language? Or does her appeal to texture, which she can experience visually and linguistically, still intensify cognitive and expressive meaning beyond its semantic denotations?

The present findings further challenge stronger claims of embodied metaphor where associations between source and target domains require a recruitment of the sensory system and a simulation of past sensations (Barsalou, 1999). Kim is fully capable of processing and using tactile metaphors without ever having experienced tactile sensations that she could then simulate to understand the metaphorical extension. Simply put, it cannot be the case that somatosensory experiences are required to process tactile metaphors, since Kim is clearly capable of doing so. However, that is not to say that somatosensory information is never used in the processing and use of tactile metaphors, as Lacey et al. (2012) show that people who have access to somatosensory information use it; rather, Kim shows that these metaphors can be understood without it.

Similar findings have been observed for other sensory domains. The ability of people with congenital blindness to understand visual metaphors has been established (Minervino et al., 2018) and metaphors using an auditory source domain are commonly attested in sign languages (Zeshan and Palfreyman, 2019). Just as hearing and sight are not necessary to process metaphors that rely on those senses, somatosensation is not necessary to process tactile metaphors. Perhaps it is the uniqueness of Kim’s condition of never having experienced tactile touch or proprioception that allowed researchers to more strongly assert the role of somatosensation in the metaphor of embodiment than that of vision and hearing.

Likewise, these findings challenge strong claims of embodied cognition , according to which all cognition, not just metaphorical language, relies on the recruitment of the body’s sensory systems. Kim demonstrates that somatosensation cannot be more necessary for abstract thought than vision and hearing. These strong proposals for embodied cognition that foreground proprioceptive experiences of one’s body and tactile experiences with the world in which one lives may be due to the fact that it is difficult for many researchers to even conceptualize the relationship differently than someone like Kim has with her body and the rarity of conditions like hers. However, Kim exists and, despite her different sensory experiences with both her body and the world around her, she is as capable of abstract thought and metaphorical language as the rest of us.

Reference: Jacob B. Phillips, Lenore A. Grenoble, Peggy Mason. The unembodied metaphor: comprehension and production of tactile metaphors without somatosensation . Frontiers in Communication , 2023; 8 DOI: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1144018