Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, and the incidence among young adults appears to be increasing. Although CVD occurring in early adulthood may have a strong genetic influence, the increasing incidence also suggests a substantial contribution from environmental and behavioral risk factors. However, the causes of CVD among young adults are understudied due to the low absolute number of people with overt CVD in this age group.

Previous studies have shown that the experience of stressful circumstances during childhood , such as material deprivation, family loss, and strained family dynamics (also known as "childhood adversities" ), is associated with an increased risk of CVD among middle-aged and older people, but very few studies have investigated the association between childhood adversities and overt CVD in early adulthood. The few studies that have been conducted among young adults have demonstrated an association between childhood adversities and CVD, but have been limited by self-reported recall of adverse events. Selection bias is a particular concern in this line of research, as disadvantaged people are less likely to participate in surveys.

Childhood is a sensitive period in which the nervous, endocrine, and immune systems are rapidly developing, and frequent or chronic exposure to adversity in childhood can influence the development of the physiological stress response. This activation may eventually alter the immune balance and lead to a more inflammatory phenotype with an increased risk of atherosclerosis and hypertension. Childhood adversity has also been linked to health-threatening behaviors associated with CVD, such as smoking, overeating, and excessive alcohol consumption as means of coping; behaviors that usually begin during adolescence.

Due to differences in etiology between different CVDs, such as ischemic heart disease (IHD) and cerebrovascular disease (CAD), the effects of childhood adversity on these diagnoses may differ, warranting separate investigation. Furthermore, CD includes diagnoses that often have a structural etiology when presenting in young adulthood. For example, subarachnoid hemorrhages are often caused by underlying aneurysms that may be present at birth. Although childhood adversity has been associated with behavioral factors that may affect the pathogenesis and growth of aneurysms, such as smoking, alcohol, and drug abuse, the role of childhood adversity in conditions of congenital etiology is uncertain and should recognize yourself.

Goals

To examine the effect of childhood adversity on the development of cardiovascular disease (CVD) between ages 16 and 38, focusing specifically on ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease.

Methods and results

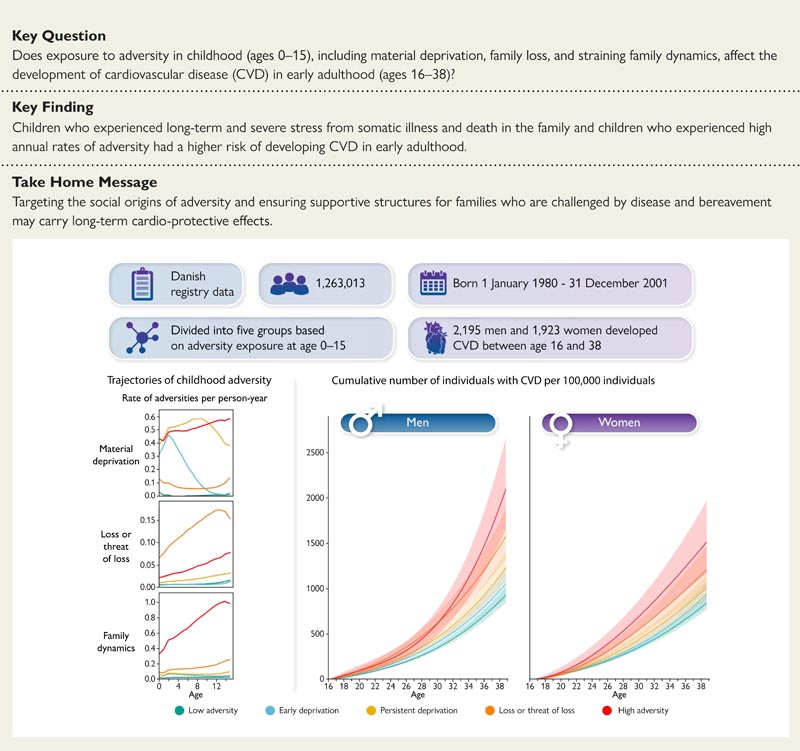

Registry data were used for all children born in Denmark between January 1, 1980 and December 31, 2001, who were alive and residing in Denmark without a diagnosis of CVD or congenital heart disease up to age 16 years, for a total of 1,263,013 people.

Cox proportional hazards and Aalen additive hazards models were used to estimate adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and adjusted risk differences for CVD from ages 16 to 38 in five adversity trajectory groups experienced among ages 0 and 15.

In total, 4,118 people developed CVD between their 16th birthday and December 31, 2018.

Compared to those who experienced low levels of adversity, those who experienced serious somatic illness and death in the family (men: adjusted HR: 1.6, 95% confidence interval: 1.4-1.8, women: 1.4, 1.2–1.

Conclusions

People who have been exposed to adversity in childhood are at higher risk of developing CVD in young adulthood compared to people with low exposure to adversity.

These findings suggest that interventions targeting the social origins of adversity and providing support to affected families may have long-term cardioprotective effects.

Discussion

In a total population sample followed prospectively from birth, we observed an increased risk of developing CVD in early adulthood among individuals exposed to childhood adversity compared to those exposed to low levels of adversity. The risk was most pronounced among people who experienced serious somatic illness and death in the family, and among people who experienced high and increasing annual rates of adversity during childhood and adolescence. The risk was generally comparable between men and women and slightly higher for ischemic heart disease (IHD) than for cerebrovascular disease (CAD), although the corresponding number of additional cases was smaller due to the low absolute number of IHD in this age group.

Our results corroborate previous studies showing increased CVD risk associated with self-reported adverse childhood experiences in middle-aged and older people.

The observed association between childhood adversity and cardiovascular disease in early adulthood may be explained in part by adverse health-related behaviors such as excessive alcohol consumption, smoking, and physical inactivity among people exposed to adversity in First years of life. Furthermore, multiple body systems undergo rapid development during childhood and the experience of adversity during this period can result in lasting alterations in the stress response, with lasting elevated inflammatory levels as a consequence . Such alterations in the physiological stress response may predispose individuals who experience childhood adversity to atherosclerosis and hypertension and mediate the effect of childhood adversity on CVD that may occur as early as early adulthood. Additional research into the specific mechanisms linking childhood adversity to IC and CD in young adulthood remains a challenge for future studies.

| In conclusion , the incidence of CVD is low in early adulthood, but increases substantially during this period. This highlights the importance of research into early life non-genetic risk factors, which may be the target of early cardiovascular prevention. The experience of adversity is common among children, and we show that children who experience severe and long-term stress due to somatic illness and death in the family, and children who are exposed to high annual rates of adversity, including deprivation, loss of strained family and family dynamics, particularly have a higher risk of developing CVD in early adulthood. Targeting the social origins of such adversity and ensuring support structures for families who, for example, face the challenge of an illness in the family can potentially have long-term cardioprotective effects . |