The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent public health measures reduced access to healthcare, which could delay care for urgent cardiovascular diseases (CVD). Additionally, SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with higher rates of heart failure, myocardial infarction, and stroke.

Population-level analyzes reported early reductions in major adverse cardiovascular events (CVD). This pattern raised concerns that subsequent rates could rise beyond expected levels, but longer-term patterns are uncertain. New England was among the first and hardest hit regions during the pandemic. Analyzes of New England populations could provide insight into the long-term implications of the pandemic for cardiovascular disease outcomes. We hypothesize that early declines in adverse CVEs were followed by rates higher than those estimated by pre-pandemic CVE trends.

Methods

We studied administrative and claims data from March 2017 to December 2021 from Harvard Pilgrim Health Care , a New England insurer with approximately 1 million members. We include commercial insurance and Medicare Advantage members ages 35 and older from Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Maine, and Connecticut with at least 6 months of enrollment. The Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institutional Review Board approved this cohort study and waived informed consent because de-identified data were used. We follow the STROBE reporting guideline.

Using claims-based algorithms and a standard approach with high specificity, we measured hospitalizations for myocardial infarction and stroke. We captured episodes of congestive heart failure (CHF), angina, and transient ischemic attack (TIA) in people presenting to the emergency department, observation unit, or hospital. We summed the above measures to create a high acuity composite CVE score. Using an interrupted time series design, we examine monthly event rates before and after March 2020.

We ran segmented linear regression models adjusted for age and sex to compare modeled post-pandemic trends to expected post-pandemic trends. Statistical analysis was performed with Stata 16 (StataCorp LLC).

Results

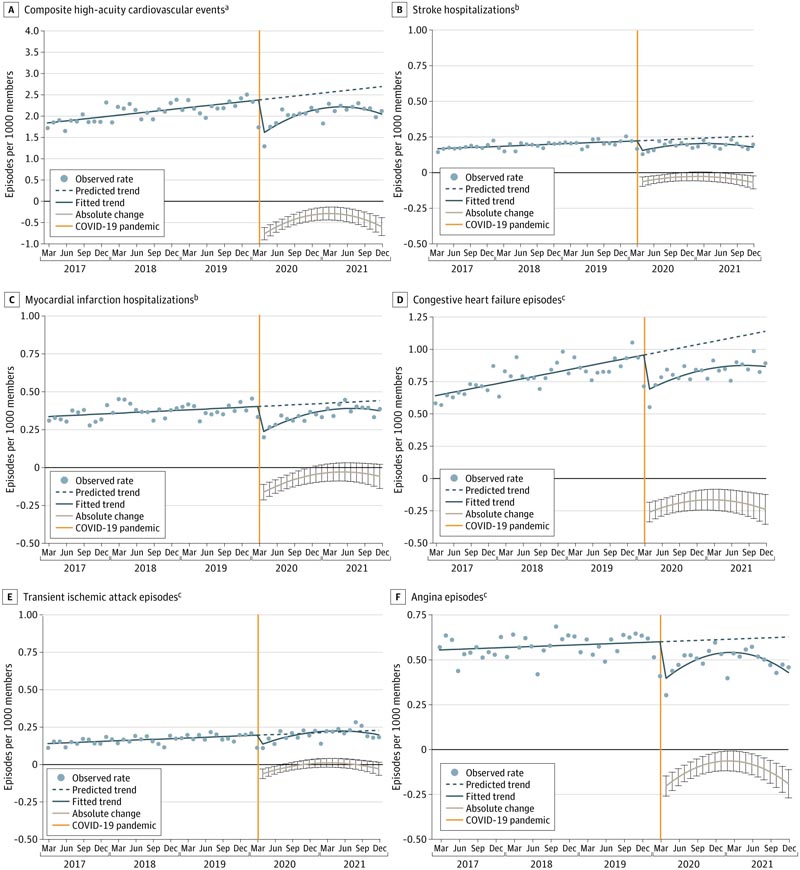

Member characteristics were similar over the study period, but members were of higher socioeconomic status (SES) than state populations. High-acuity composite CVEs initially decreased in April 2020 by 26.6% (95% CI, −31.4 to −21.8).

Rates remained below expected levels in March 2021 (−9.6%; 95% CI, −14.5 to −4.8) and December 2021 (−19.8%; 95% CI, −14.5 to −4.8). %, −26.2 to −13.5).

Stroke hospitalizations initially decreased by 27.0% (95% CI, −39.5 to −14.5), remaining below expectations in February 2021 (−11.8%, 95% CI %, −23.1 to −0.5) and were below expected levels in December 2021. (-27.3%; 95% CI, -42.4 to -12.2).

Hospitalizations for myocardial infarction initially decreased by 27.8% (95% CI, −35.8 to −19.8), but were not statistically different than expected in January 2021.

CHF episodes initially decreased by 26.1% (95% CI, −33.3 to −18.9) and were below expected levels in March 2021 (−15.8%; 95%, −22.6 to −9.0) and were lower than expected in December 2021 (−22.1%; 95% CI, −31.5 to −12.7).

Angina episodes followed similar sustained reduction trends , while TIA episodes were not statistically different than expected in August 2020.

Figure : Monthly rates of cardiovascular events in a commercially insured population aged 35 years and older.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic was not associated with long-term increases in adverse cardiovascular events (CVE) among commercially insured New England residents presenting for care.

Instead, we detected sustained reductions in TIA, CHF, and angina episodes. Factors explaining these trends could include non-presentation of patients during the 21-month follow-up, cardiovascular deaths outside the medical system, COVID-19-related deaths of people at risk for high-acuity CVD, decreasing overdiagnosis due to a reduced emergency room care and hospital volumes, home heart failure management, and reductions in adverse events. More studies are needed to identify and quantify these factors.

The study findings may not generalize to other regions of the US, to people without commercial insurance, or to populations with lower socioeconomic status. For example, Massachusetts was unusual in not experiencing an increase in cardiovascular deaths during the first two months of the pandemic. Additional research can examine regions with lower concentrations of physicians, lower SES, and higher CVD burden. This study, combined with future studies, could help policymakers and insurers anticipate changes in key health outcomes during periods of limited access to health care.

Editorial

The Paradoxical Decline in Cardiovascular Hospitalizations in the US

Source: The Paradoxical Decline in Cardiovascular Hospitalizations in the US. Rishi K. Wadhera, MD, MPP, MPhil. JAMA Health Forum. 2024;5(1):e234334. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2023.4334

The sharp decline in hospitalizations for acute cardiovascular conditions during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic led doctors across the country to ask, "Where have all the heart attacks and strokes gone?" Many were concerned that the sudden and precipitous decline was due to negative indirect effects of the pandemic, such as patients avoiding emergency care. Others speculated that these patterns reflected a real change in the incidence of acute cardiovascular events. Understanding the factors that drove the decline in cardiovascular hospitalizations (and whether these types of hospitalizations recovered as the pandemic progressed) has critical implications for public health as the United States emerges from the pandemic.

In this issue of JAMA Health Forum , a study by Wharam and colleagues provides important information. The authors leveraged administrative claims data from a large insurer in the New England area to compare monthly rates of acute cardiovascular hospitalizations (myocardial infarction, angina, congestive heart failure, stroke, and transient ischemic attack) before and after baseline. of the pandemic (March 2020) and used an interrupted time series design to compare observed rates with expected rates. Their study has two key findings.

First, hospitalizations for acute cardiovascular diseases initially decreased by 33% during the first months of the pandemic, ranging from a relative reduction of 30% (congestive heart failure) to 42% (myocardial infarction). Second, hospitalizations did not recover to (or exceed) expected levels later in the pandemic (through December 2021) and remained considerably lower for many cardiovascular conditions.

What explains the strong and persistent decline in acute cardiovascular hospitalizations almost two years after the start of the pandemic? The most concerning explanation is that many patients avoided seeking hospital care for emerging conditions for fear of contracting COVID-19. Survey data during the early months of the pandemic in 2020 found that about 1 in 3 adults reported they would stay home if they thought they were having a heart attack or stroke due to fear of going to the hospital. As of mid-2021, 1 in 5 adults continued to report delaying or not seeking needed medical care, with the highest rates of delayed care occurring among racial and ethnic minority groups.

These data are consistent with my own clinical experience as a cardiologist in Massachusetts. More than a year into the pandemic, I remember receiving phone calls from adults with sudden chest pain, many of whom ultimately refused to go to the hospital to be evaluated and treated out of fear. Additionally, patients I cared for on cardiology wards expressed a nearly ubiquitous desire to leave the hospital as soon as possible due to concerns about contracting COVID-19. Many were admitted with complications from cardiovascular events (e.g., heart attack) that they had experienced several weeks or even months earlier but had not initially sought care for fear of being admitted to the hospital.

In fact, during this period of several months, I cared for more patients with late complications of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (the most serious type of heart attack that often requires urgent life-saving treatment) than I ever had before. attended over the course of my professional career. Colleagues across the country shared similar stories of patients who experienced adverse cardiovascular outcomes, either from avoiding medical care or from delays in care related to strain on the healthcare system.

Another likely explanation for the substantial and persistent decline in hospitalizations is that COVID-19-related deaths occurred disproportionately among adults who would have eventually experienced an acute cardiovascular event. Patients with chronic diseases such as diabetes and obesity (established risk factors for heart attack and stroke) were at higher risk of COVID-19-related death.

Wharam and colleagues hypothesized that the early reduction in cardiovascular hospitalizations they observed would be followed by an increase above expected levels in subsequent months due to pent-up demand for health care services. The absence of such recovery in their study likely reflects, at least in part, a form of survivorship bias. There was a large increase in population deaths during the pandemic, including those that occurred outside the medical system; many of the highest-risk patients who would have come to the hospital with an acute cardiovascular event had died of COVID-19.

Wharam and colleagues’ study, combined with top-line knowledge, provides clarity on the predominant mechanisms driving the decline in cardiovascular hospitalizations during the pandemic. Even clearer, however, is the devastating effect the pandemic has had on cardiovascular health. The decrease in cardiovascular hospitalizations should not be interpreted as a decrease in the incidence of acute cardiovascular events, given the sharp increase in population-level cardiovascular deaths that occurred during the pandemic, which erased nearly a decade of progress. Additionally, many adults experienced disruptions in outpatient care, preventive screenings, and treatment of chronic diseases (e.g., hypertension, diabetes), as well as worsening social determinants of health (e.g., unemployment, deepening financial difficulties). Together, these indirect effects may have serious and far-reaching repercussions on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality long after the pandemic ends.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had an enormous influence on the delivery of cardiovascular and health care in the US, and the consequences of the fallout from the pandemic are yet to come. Clinicians, health systems, and public health leaders will need to prepare for the tsunami of risk factors and cardiovascular disease that will likely emerge in the years following the pandemic.