Inflammation and poverty as individual and combined predictors of 15-year mortality risk in middle-aged and older adults in the US. Summary Background: Chronic systemic inflammation and poverty are linked to increased risk of mortality. The objective of this study was to determine whether there is a synergistic effect of the presence of inflammation and poverty on the 15-year risk of all-cause mortality, heart disease, and cancer among American adults. Methods: We analyzed the nationally representative National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 1999 to 2002 with records linked to the National Death Index through December 31, 2019. Among adults aged 40 years and older, the risk 15-year mortality rates associated with inflammation, C-reactive protein (CRP), and poverty were assessed in Cox regressions. The outcomes were all-cause mortality, heart disease, and cancer. Results: Individuals with an elevated CRP of 1.0 mg/dL and poverty had a higher risk of adjusted all-cause mortality at 15 years (HR = 2.45; 95% CI: 1.64, 3.67) that people with a low CRP were above poverty. For individuals with only one risk characteristic, low inflammation/poverty (HR = 1.58; 95% CI: 1.30, 1.93), inflammation/above poverty (HR = 1.59, CI 95%: 1.31, 1.93), the risk of mortality was essentially the same and substantially lower than the risk for adults with both. People with elevated inflammation and living in poverty experience a 127% elevated 15-year risk of heart disease mortality and a 196% elevated 15-year cancer mortality risk. Discussion: This study extends previous research showing increased mortality risk from poverty and systemic inflammation to indicate that there is a potential synergistic effect for increased mortality risk when an adult has higher inflammation and lives in poverty. |

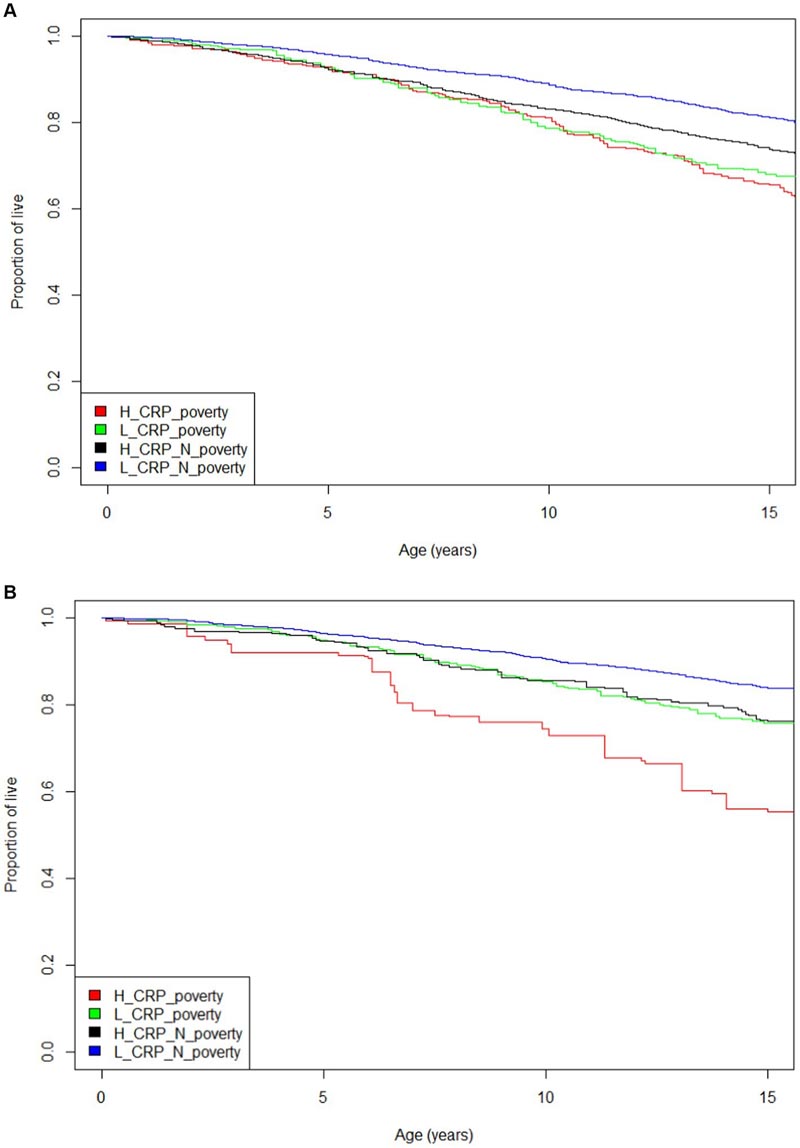

Figure: Cox proportional hazard analysis adjusted for mortality risk presented in Table 2 confirmed the trends observed in the unadjusted Kaplan-Meier curves. The results of the analysis with inflammation defined as CRP 0.3 mg/dL suggest that individuals with high levels of CRP have essentially the same risk of mortality whether they live in poverty or above the poverty level. However, analysis defining inflammation as CRP at 1.0 mg/dL shows that there is a synergistic effect on mortality risk when a person has high inflammation and lives in poverty.

Comments

The combined effect of poverty and inflammation on mortality is worse than expected from separate effects

In the United States, approximately 37.9 million people, or 11.4% of the population, were living below the poverty line in 2022. It is well demonstrated that poverty negatively affects physical and mental health. For example, people living in poverty are at higher risk of mental illness, heart disease, hypertension, and stroke, and have higher mortality and lower life expectancy. The mechanisms by which poverty impacts health outcomes are multiple: for example, people living in poverty have reduced access to healthy food, clean water, safe housing, education, and health care.

Now, researchers have shown for the first time that the effects of poverty can combine synergistically with another risk factor, chronic inflammation , to further reduce health and life expectancy. They found that the health outcomes of Americans living in poverty and with chronic inflammation are significantly worse than expected from their health effects alone. The results are published in Frontiers in Medicine .

"Here we show that doctors should consider the effect of inflammation on the health and longevity of people, especially those living in poverty," said lead author Dr. Arch Mainous, a professor at the University of Florida. .

Inflammation is a natural physiological reaction to infection or injury, essential for healing. But chronic inflammation (caused by exposure to environmental toxins, certain diets, autoimmune disorders like arthritis, or other chronic diseases like Alzheimer’s) is a known risk factor for disease and mortality, as is poverty.

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)

Mainous and colleagues analyzed data from adults ages 40 and older, enrolled between 1999 and 2002 in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), and followed them through December 31, 2019. The NHANES, conducted since 1971 by the National Center for Health Statistics, tracks the health and nutrition status of American adults and children. The NHANES allows for estimates of the US population represented by the cohort, and this study represented nearly 95 million adults. The authors combined NHANES data with National Death Index records to calculate mortality rates over a 15-year period after enrollment.

Among other demographic data, NHANES records household income. The authors divided this by the official poverty line to calculate the "poverty index," a standard measure of poverty.

Chronic inflamation

Whether the participants suffered from severe inflammation was deduced from their plasma concentration of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), produced by the liver in response to the secretion of interleukins by immune and fat cells. The concentration of hs-CRP, included in the NHANES data, is a readily available, informative, and well-studied measure of inflammation: for example, elevated concentrations are known to increase the risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality.

Normally, a concentration greater than 0.3 mg/dl hs-CRP is considered an indication of chronic systemic inflammation, but Mainous et al. It also considered the more stringent threshold of 1.0 mg/dL in a separate analysis.

The authors classified the participants into four groups: with or without chronic inflammation and living below the poverty line or not. By comparing the 15-year mortality rate between these, they could study the effects of poverty and inflammation separately and together.

Synergistic effect

“We found that participants with inflammation or poverty each had about a 50% increased risk of all-cause mortality. In contrast, people with inflammation and poverty had a 127% higher risk of heart disease mortality and a 196% higher risk of cancer mortality,” said Dr. Frank A. Orlando, associate professor at the University of Florida and second author of the study.

“If the effects of inflammation and poverty on mortality were additive, a 100% increase in mortality would be expected for people where both are applied. But since the observed increases of 127% and 196% are much larger than 100%, we conclude that the combined effect of inflammation and poverty on mortality is synergistic.”

Routine screening for both risk factors?

There are a wide variety of treatments for systemic inflammation, ranging from diet and exercise to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and steroids. The current results suggest that doctors could consider screening socially disadvantaged people for chronic inflammation (already a medically vulnerable group) and, if necessary, treating them with such anti-inflammatory drugs. However, steroids and NSAIDs are not without risks when taken long term. Therefore, more research will be needed before patients are routinely prescribed it in clinical practice to decrease systemic inflammation.

“It is important that guideline panels address this issue to help clinicians integrate inflammation screening into their standard of care, particularly for patients who may have factors that put them at risk for chronic inflammation, including living in poverty. It is time to go beyond documenting the health problems that inflammation can cause and try to solve them,” Mainous concluded.

In conclusion , inflammation and poverty are well-known mortality risk factors, but when both exist simultaneously and CRP is >1.0 mg/dL, they have the potential to increase mortality more than one would expect from an effect additive. This is particularly concerning in socially disadvantaged patients who are already a medically vulnerable population. Furthermore, elevated inflammation is often not recognized in asymptomatic populations. Perhaps screening for elevated CRP in vulnerable populations could be particularly useful. Although both inflammation and poverty are modifiable risk factors, in clinical practice chronic diseases associated with inflammation, such as cardiovascular disease, are more likely to be prevented by a healthy lifestyle than reversed. |