Mortality from all causes worldwide has decreased and this decrease is expected to continue. This positive trend is attributable to improvements in a wide range of health determinants, such as access to and quality of health care, technological advances, poverty reduction, access to water and sanitation, labor rights and, fundamentally, access to education.

Not everyone has benefited equally from these improvements and reducing disparities in mortality rates between socioeconomic groups has become a key objective for many nations and international organizations. An important milestone in these efforts has been the 2008 WHO commission on social determinants of health, which advocated reducing disparities in mortality by addressing social factors that lead to poor health and mortality.

The positive relationship between more schooling and better health is well established. The main pathways through which education can improve health are believed to include social and psychosocial, economic and cognitive benefits. As such, education has been recognized as a key determinant in achieving socio-economic development, social and gender empowerment and social mobility. These are all necessary prerequisites to survive and thrive. This focus on the social determinants of population health is reflected in the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in their entirety and, especially, in SDGs 4.1 and 4.3, which aim to ensure that children complete education primary and secondary, and that adults have equal access to the same tertiary education, respectively.

The global distribution of educational attainment has changed dramatically over the past five decades, and these changes have been associated with effects on mortality. In particular, parental education has been highlighted for its effect on infant mortality rates, where it has been shown that each additional year of maternal education reduces the mortality of children under 5 years of age by 3.0% and that each year of paternal education reduces this risk by 1.6%.

Background

The positive effect of education in reducing adult mortality from all causes is known ; however, the relative magnitude of this effect has not been systematically quantified. The objective of our study was to estimate the reduction in adult all-cause mortality associated with each year of schooling worldwide.

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we assessed the effect of education on adult all-cause mortality. The databases PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Embase, Global Health (CAB), EconLit, and Sociology Source Ultimate were searched from January 1, 1980 to May 31, 2023. Reviewers (LD, TM, HDV, CW, IG, AG, CD, DS, KB, KE and AA) evaluated each registry for individual-level data on educational level and mortality. A single reviewer extracted data into a standard template from the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors Study.

We excluded studies that relied on ecological or case-crossover study designs to reduce the risk of bias from unlinked data and studies that did not report key measures of interest (all-cause adult mortality).

Mixed-effects meta-regression models were implemented to address heterogeneity in baseline and exposure measures across studies and to adjust for study-level covariates. This study was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42020183923).

17,094 unique records were identified, 603 of which were eligible for analysis and included data from 70 locations in 59 countries, yielding a final data set of 10,355 observations.

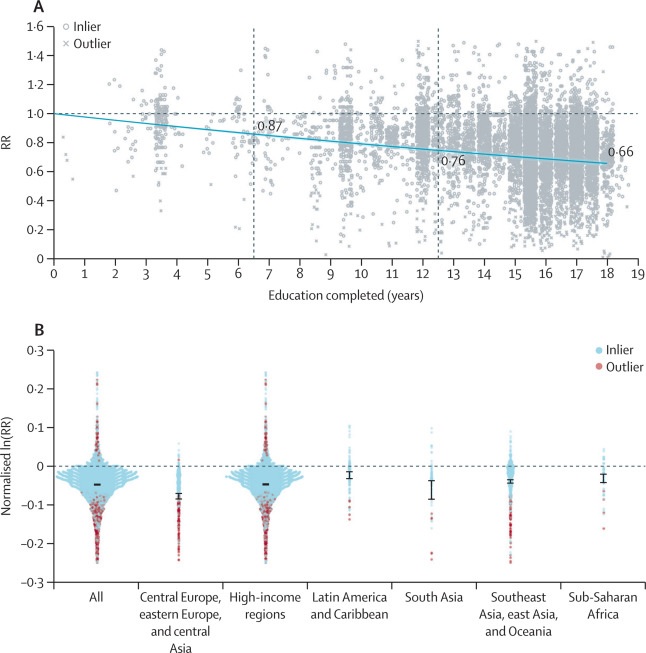

Education showed a dose-response relationship with adult all-cause mortality, with an average reduction in mortality risk of 1.9% (95% uncertainty interval: 1.8-2.0) per additional year of Education.

The effect was larger in younger than older age groups, with an average reduction in mortality risk of 2.9% (2.8–3.0) associated with each additional year of adult education 18 to 49 years compared to a 0.8% reduction (0.6–1.0) for adults over 70 years.

We found no differential effect of education on all-cause mortality by sex or sociodemographic index level. We identified publication bias (p<0.0001) and identified and reported estimates of heterogeneity between studies.

Figure: Adult all-cause mortality by educational level (A) The relationship between education and the risk of adult all-cause mortality across the range of 0 to 18 years of education, superimposed on level input data of exposure to education and effect size. (B) The distribution of input data effect sizes across superregions. The normalized ln(RR) can be interpreted as the instantaneous slope of the RR curve implied by each study. Data are overlaid with a synthesized average effect size (shown in black). Ln=natural logarithm. RR=relative risk.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis that quantifies the importance of years of schooling in reducing adult mortality , the benefits of which extend into old age and are substantial across sexes and economic contexts.

This work provides compelling evidence of the importance of education in improving life expectancy and supports calls for greater investment in education as a crucial path to reducing global inequalities in mortality.

This systematic review and meta-analysis presents a comprehensive summary of the dose-response relationship between education and all-cause mortality in adults . Our findings suggest that low education is a risk factor for mortality in adults , after controlling for age, sex, and marital status. We found that, on average, an adult with 12 years of schooling has a 24.5% (95% UI 23.0–26.1) lower risk of mortality compared to an adult without schooling, with an average reduction in mortality of 1.9% (1.8–2.0) per year of schooling. The protective effect of higher education on mortality was significant at all ages, sex, period, birth cohort, and sociodemographic index level and was not attenuated at higher levels of education.

In particular, the effects of education on mortality risk are known to be mediated by health behaviors. For example, a lower level of education is correlated with higher rates of cardiovascular disease and cancer mortality. Higher education provides access to better jobs, higher incomes, quality health care, and greater health literacy. Furthermore, more educated people tend to develop a broader set of social and psychological resources that shape their health and lifespan. Although there is some evidence that the returns to schooling at higher levels are diminishing, often attributed to the burden of non-communicable diseases and some behavioral risk factors in high-income settings, we find no evidence of a diminishing benefit in these analyses. .

The breakdown by age group indicates that the protective effect of education is significant throughout the age period, but is greater at younger ages, which is consistent with previous studies. As an individual reaches older age, genetic disposition, daily habits, diet, or other socioeconomic predictors of mortality appear to have a greater influence on mortality risk than their educational level. However, despite these influences, educational inequalities in mortality are persistent across the lifespan, and the pattern remains the same across periods and cohorts. The differences observed between the age groups captured in our data set contribute to the heterogeneity of all observed effect measures.

Our finding that the protective effect of education did not differ significantly between sexes requires further investigation. Previous studies, particularly from high-income countries, have reported sex differences in the protective effect of education, where a shift over time has been observed from a stronger protective effect of education among female populations to a more recent marginal advantage for male populations. This variability between sexes is also observed in low-income countries. These region-specific or period-specific trends may be hidden in our overall analysis. However, women’s education has been shown to have a stronger intergenerational effect than men’s education and efforts directed at the education of girls at primary and secondary age are still needed, particularly in regions of the world where Girls’ education still lags behind that of boys, to reduce existing inequalities in educational attainment and improve future population health.

Funding : Research Council of Norway and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.