In this study, we investigated whether lifestyle changes were related to better health outcomes in people with cardiovascular diseases (CVD). Self-reported lifestyle behaviors (smoking, waist circumference, alcohol consumption, and physical activity) were assessed at the time of cohort inclusion and again approximately 10 years later. The results emphasize the importance of choosing healthy lifestyles, even for people already diagnosed with CVD, and suggest that it is never too late to improve lifestyle .

Key results

|

Goals

To quantify the relationship between self-reported long-term lifestyle changes (smoking, waist circumference, physical activity, and alcohol consumption) and clinical outcomes in patients with established cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Methods and results

Data were used from 2011 participants (78% men, age 57 ± 9 years) from the Utrecht Cardiovascular Cohort: Second Manifestation of Arterial Disease who returned for a reassessment visit (SMART2) after approximately 10 years . Self-reported lifestyle change was classified as persistently healthy, improved, worsened, or persistently unhealthy.

Cox proportional hazard models were used to quantify the relationship between lifestyle changes and the risk of mortality (cardiovascular) and type 2 diabetes (T2D). Fifty-seven percent of participants were persistently healthy, 17% improved their lifestyle, 8% worsened, and 17% were persistently ill.

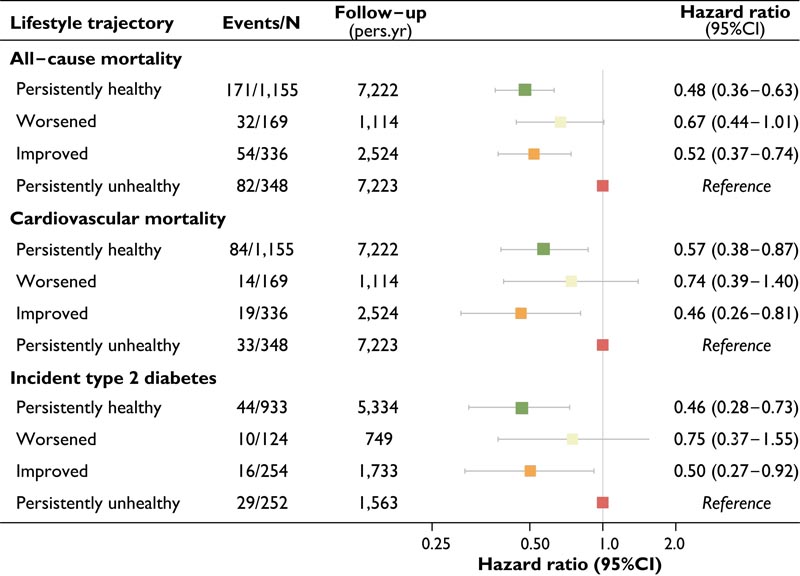

During a median follow-up time of 6.1 (interquartile range 3.6 to 9.6) years after the SMART2 visit, 285 deaths occurred and 99 new diagnoses of type 2 diabetes were made. Compared with a lifestyle persistently unhealthy, people who maintained a healthy lifestyle had a lower risk of all-cause mortality [hazard ratio (HR) 0.48, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.36-0.63 ], cardiovascular mortality (HR 0.57, 95% CI 0.38–0.87), and incident type 2 diabetes (HR 0.46, 95% CI 0.28–0.73).

Similarly, those who improved their lifestyle had a lower risk of all-cause mortality (HR 0.52, 95% CI 0.37–0.74), cardiovascular mortality (HR 0.46, 95% CI 0.26–0.81) and incident type 2 diabetes (HR 0.50, 95% CI 0.27–0.92).

Figure: Risk of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and incident type 2 diabetes for a different lifestyle trajectory. Hazard ratio of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality compared to a persistently unhealthy lifestyle. Risk indices were adjusted for age, sex, and educational level. Time of in-person follow-up years after the SMART2 study visit. HR: risk index; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Conclusions This study evaluated the relationship between self-reported lifestyle changes and mortality (cardiovascular) and type 2 diabetes. The findings emphasize the pressing need for continued attention to maintain or adopt a healthy lifestyle within the clinical management of patients with CVD. By incorporating lifestyle interventions into their treatment plans, healthcare providers can potentially mitigate the risk of cardiovascular mortality and type 2 diabetes for their patients. Ultimately, these findings underscore the profound impact that lifestyle choices can have on the outcomes and overall well-being of CVD patients. |