Background

The effects of pharmacologic blood pressure lowering in normal or high-normal blood pressure ranges in people with or without preexisting cardiovascular disease remain uncertain. Data from individual participants in the randomized trials were analyzed to investigate the effects of blood pressure-lowering treatment on the risk of major cardiovascular events based on baseline systolic blood pressure levels.

Methods

We did a meta-analysis of individual participant-level data from 48 randomized trials of pharmacological blood pressure-lowering medications versus placebo or other classes of blood pressure-lowering medications, or between more versus less intensive treatment regimens, that had at least 1000 people. years of follow-up in each group.

We excluded trials conducted exclusively with participants with heart failure or short-term interventions in participants with acute myocardial infarction or other acute settings. Data from 51 studies published between 1972 and 2013 were obtained by the Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trials Collaboration (University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom).

Data were pooled to investigate the stratified effects of blood pressure-lowering treatment in participants with and without prevalent cardiovascular disease (i.e., any report of stroke, myocardial infarction, or ischemic heart disease before randomization), overall and in seven systolic blood pressure categories (ranging from <120 to ≥170 mm Hg).

The primary outcome was a major cardiovascular event (defined as a combination of fatal and non-fatal stroke, fatal or non-fatal myocardial infarction or ischemic heart disease, or heart failure resulting in death or requiring hospital admission), analyzed by intention to treat.

Results

Data from 344,716 participants from 48 randomized clinical trials were available for this analysis. Mean systolic/diastolic blood pressures before randomization were 146/84 mm Hg in participants with prior cardiovascular disease (n = 157,728) and 157/89 mm Hg in participants without prior cardiovascular disease (n = 186,988).

There was a substantial spread in participants’ blood pressure at baseline, with 31,239 (19.8%) of participants with prior cardiovascular disease and 14,928 (80%) of individuals without prior cardiovascular disease having a systolic blood pressure less than 130 mm Hg.

The relative effects of blood pressure-lowering treatment were proportional to the intensity of systolic blood pressure reduction.

After a median follow-up of 4·15 years (Q1 – Q3 2·97–4·96), 42,324 participants (12·3%) had at least one major cardiovascular event.

In participants without prior cardiovascular disease at the start of the study, the incidence rate of developing a major cardiovascular event per 1000 person-years was 31 9 (95% CI 31 3-32 5) in the comparator group and 25 9 (25 4-26.4) in the intervention group.

In participants with prior cardiovascular disease at baseline, the corresponding rates were 39·7 (95% CI: 39·0–40·5) and 36·0 (95% CI: 35·3–36·7). ), in the comparator and intervention groups, respectively.

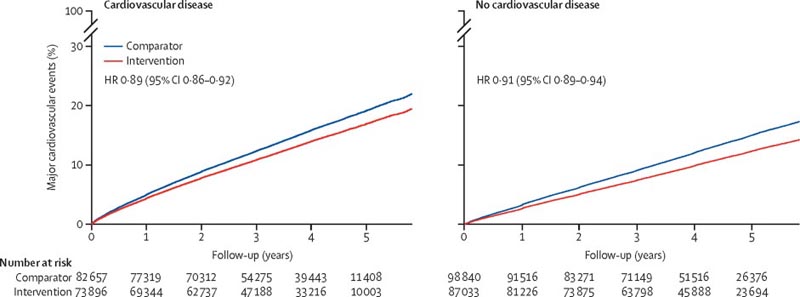

Rates of major cardiovascular events per 5 mm Hg reduction in systolic blood pressure, stratified by treatment assignment and cardiovascular disease status at baseline. Major cardiovascular events were defined as a composite of fatal or nonfatal stroke, fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction or ischemic heart disease, or heart failure causing death or requiring hospital admission. HR = risk index.

The hazard ratios (HR) associated with a reduction in systolic blood pressure by 5 mm Hg for a major cardiovascular event were 0·91, 95% CI 0·89–0·94 for participants without prior cardiovascular disease and 0·89 , 0 · 86-0 · 92, for those with previous cardiovascular disease.

In stratified analyses, there was no reliable evidence of heterogeneity of treatment effects on major cardiovascular events by baseline cardiovascular disease status or systolic blood pressure categories.

Interpretation In this large-scale analysis of randomized trials, a 5 mm Hg reduction in systolic blood pressure reduced the risk of major cardiovascular events by approximately 10% , regardless of previous diagnoses of cardiovascular disease, and even at normal or elevated values. - normal blood pressure. These findings suggest that a fixed degree of pharmacological blood pressure lowering is equally effective for primary and secondary prevention of major cardiovascular disease, even at blood pressure levels not currently considered for treatment. Physicians who communicate to their patients the indication for blood pressure-lowering treatment should emphasize its importance in reducing cardiovascular risk rather than focusing on blood pressure reduction itself. |

Research in context

Added value of this study

In this collaborative project, we collected individual participant-level data (IPD) from eligible large-scale trials of blood pressure-lowering treatment. With access to ENI from approximately 350,000 patients randomized to treatment in 48 trials, this analysis is the largest and most detailed investigation of the stratified effects of pharmacological blood pressure lowering.

Participants were first divided into two groups: those with a prior diagnosis of cardiovascular disease and those without. Each group was then divided into seven subgroups based on systolic blood pressure at study entry (<120, 120-129, 130-139, 140-149, 150-159, 160-169, and ≥170 mm Hg).

Over an average of 4 years of follow-up, a 5 mm Hg reduction in systolic blood pressure reduced the relative risk of major cardiovascular events by 10%.

The risks of stroke, heart failure, ischemic heart disease, and death from cardiovascular disease were reduced by 13%, 13%, 8%, and 5%, respectively.

The relative risk reductions were proportional to the intensity of the blood pressure decrease. Neither the presence of cardiovascular disease nor the blood pressure level at the beginning of the study modified the treatment effect.

Implications of all available evidence

This study calls for a change in clinical practice that predominantly limits antihypertensive treatment to people with higher than average blood pressure values.

Based on this study, the decision to prescribe blood pressure medications should not be based simply on a prior diagnosis of cardiovascular disease or an individual’s current blood pressure. Rather, blood pressure medications should be considered an effective tool for preventing cardiovascular disease when a person’s cardiovascular risk is high.

This study does not support recommendations specifying a minimum blood pressure threshold for initiation or intensification of treatment, or a minimum level for blood pressure reduction.

Discussion

In this largest source of randomized evidence for the effects of blood pressure lowering on cardiovascular disease and death, we find that the proportional effects of blood pressure lowering on cardiovascular outcomes are similar in people with and without cardiovascular disease. previous and in all categories of initial systolic pressure up to less than 120 mm Hg.

| On average, a 5 mm Hg reduction in systolic blood pressure reduced the risk of a major cardiovascular event by approximately 10%; the corresponding proportional reductions in the risk of stroke, heart failure, ischemic heart disease, and cardiovascular death were 13%, 13%, 8%, and 5%, respectively. |

Reference epidemiological studies have provided convincing evidence of a log-linear relationship between blood pressure and cardiovascular disease risk across the physiological range of blood pressure, without a threshold below which the associations were shown to differ materially.

Our study fills the evidence gaps and provides compelling evidence from randomized trials for the beneficial effects of blood pressure-lowering treatment across the spectrum of systolic blood pressure in people with or without a known diagnosis of cardiovascular disease.

Our findings do not support concerns about a J-shaped association between blood pressure and cardiovascular outcomes in observational studies, and rule out suggestions that blood pressure-lowering treatment is only effective when blood pressure is above a certain threshold.

These findings have important implications for clinical practice. Currently, the approach to prescribing antihypertensives depends on an individual’s prior history of cardiovascular disease and blood pressure value. Although guidelines vary in the degree of emphasis on these two risk factors, they invariably modify recommendations based on them. For example, New Zealand has largely abandoned the approach to treating hypertension and recommends screening for overall cardiovascular risk in adults as the first step toward clinical decision making.

However, in the second stage, people classified as high risk for cardiovascular disease must also have high blood pressure to qualify for antihypertensive treatment. Most other guidelines have an even greater reliance on blood pressure, often with explicit criteria for diagnosis of hypertension in the first stage and then consideration of treatment in the second stage in a subset of hypertensive participants.

For example, in England, antihypertensive treatment for the primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases is not considered relevant when baseline systolic blood pressure is less than 140 mm Hg. Most guidelines also define a minimum level for lowering blood pressure, assuming that lowering blood pressure below a common threshold would be ineffective or have an uncertain or even harmful effect.

Our study requires a revision of these guidelines.

The finding that a fixed, modest degree of blood pressure reduction is expected to lead to similar relative reductions in the risk of cardiovascular events, regardless of current blood pressure or the presence of ischemic heart disease and stroke, requires consideration of a treatment to lower blood pressure for any individual who has a sufficiently high absolute risk of cardiovascular disease.

| By viewing antihypertensives as a tool to reduce cardiovascular risk, rather than simply lowering blood pressure, physicians are no longer required to make decisions according to an arbitrary and confusing classification of hypertension. |

The need and burden for accurate blood pressure measurement is also reduced. This will not only simplify decision-making, management, and communication of treatment strategies with participants, but, as shown in previous model studies, will also lead to more efficient care compared to alternative strategies that rely more than the absolute values of blood pressure.

However, the fact that stratified effects were similar across the phenotypes investigated does not necessarily mean that all patients are worth treating, or that there is no particular subgroup for which proportional risk reductions are greater or lesser. Even in the absence of heterogeneous treatment effects depending on baseline blood pressure and cardiovascular disease status, clinical decisions to treat elevated blood pressure will require consideration of factors such as an individual’s overall risk for future cardiovascular events, the potential risk of adverse effects, the cost of treatment and patient preferences.

In this context, our study emphasizes the importance of using multivariate risk prediction tools that have also been shown to be less sensitive to random errors of individual risk factors.

Our results also do not mean that it is appropriate to simply target blood pressure reduction to a common threshold for all individuals. Determination of the optimal magnitude of blood pressure ideally requires a comparison of different intensities of blood pressure reduction at different reference blood pressures.

Our study design cannot directly address this question. Rather, we show that the same fixed level of blood pressure reduction is expected to lead to similar levels of relative risk reduction over a wide range of baseline blood pressure levels, regardless of cardiovascular disease status.

In our prespecified analysis, we report the effects of a systolic blood pressure reduction of 5 mm Hg. However, as our meta-regression analysis shows, greater reductions in relative risk are expected with greater reductions in blood pressure, as is the case with multiple blood pressure-lowering drugs.

Therefore, the feasibility of modest systolic blood pressure reductions of approximately 15 mm Hg across all blood pressure strata, as shown in another BPLTTC study, along with the consistency of the effects shown in the present study, calls into question the scientific validity of defining a common blood pressure goal for all participants.

This study provides evidence against the widely held view that an individual’s blood pressure or prior diagnosis of cardiovascular disease per se are key factors in selecting or deselecting participants for blood pressure-lowering treatment.

These findings call for revision of global clinical guideline recommendations and suggest that antihypertensive medications are best viewed as treatment options for the prevention of cardiovascular disease regardless of an individual’s blood pressure level and prior history of cardiovascular disease. .

For people at risk for cardiovascular disease, drug treatment to lower blood pressure should become a cornerstone of risk prevention, regardless of cardiovascular disease or blood pressure status.

Funding: British Heart Foundation, UK National Institute for Health Research and Oxford Martin School.