Delirium, an acute state of confusion characterized by a fluctuating course, attention deficits, and severe behavioral disorganization, can affect more than half of patients admitted to the ICU. Risk factors for delirium in the ICU include age, severity of illness, and need for mechanical ventilation.

Delirium in critically ill patients is associated with adverse outcomes, including longer hospital stays, increased risk of cognitive impairment, and in-hospital and ICU mortality.

Most studies of ICU delirium have reported ICU or hospital mortality. Few studies have reported outcomes after hospital discharge ; those that have been performed at individual centers with up to 1 year of follow-up focused on ICU subpopulations and reported conflicting results. There is a growing body of literature suggesting that critical illness and ICU care have long-term consequences.

Given the high prevalence of delirium in critically ill patients and its well-documented consequences in the ICU and hospital, it is important to understand if and how delirium influences the health of patients recovering from critical illness.

Therefore, a large, multicenter, population-based cohort of critically ill patients admitted to the ICU was followed up to 2.5 years after hospital discharge to examine the association between ICU delirium and posthospital mortality and use of health resources.

Justification:

Delirium is common in the ICU and portends worse outcomes in the ICU and in the hospital. The effect of delirium in the ICU on post-hospital discharge mortality and the use of healthcare resources is less known.

Goals:

To estimate mortality and the use of health resources 2.5 years after hospital discharge in critically ill patients admitted to the ICU.

Methods:

This is a population-based, propensity score-matched, retrospective cohort study of adult patients admitted to 1 of 14 medical-surgical ICUs from January 1, 2014 to June 30, 2016.

Delirium was measured using the 8-item intensive care delirium screening checklist. The primary outcome was mortality.

The secondary outcome was a composite measure of subsequent emergency department visits, hospital readmission, or mortality.

Measurements and main results:

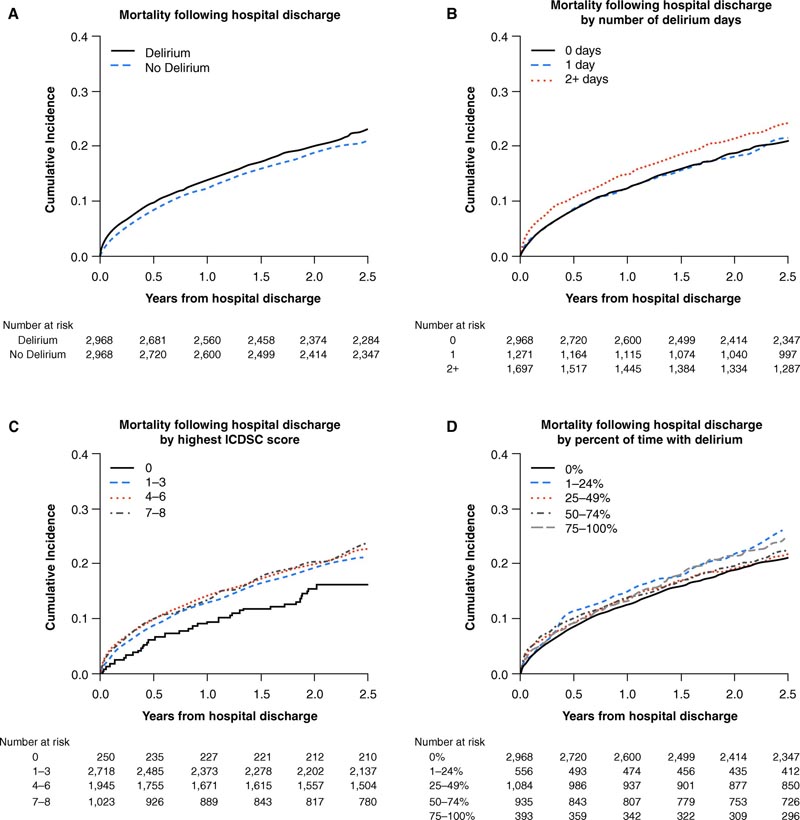

There were 5,936 patients with and without a history of incident delirium who survived to hospital discharge. Delirium was associated with increased mortality from 0 to 30 days after hospital discharge (hazard ratio, 1.44 [95% confidence interval, 1.08–1.92]).

There were no significant differences in mortality more than 30 days after hospital discharge (delirium: 3.9%, no delirium: 2.6%).

There was a persistently increased risk of emergency department visits, hospital readmissions, or mortality after hospital discharge (hazard ratio, 1.12 [95% confidence interval, 1.07–1.17]) throughout the period of the study.

Delirium and cumulative incidence of mortality (A) after hospital discharge among all patients, (B) stratified by number of days of delirium, (C) stratified by highest ICDSC score, and (D) stratified by percentage of time with delirium for the propensity score matching cohort. ICDSC = Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist.

Discussion

In this multicenter, propensity score-matched, population-based cohort study, we found that having had delirium in the ICU was associated with an increased risk of mortality in the first 30 days after hospital discharge.

Delirium was also associated with increased emergency department visits, hospital readmissions, or mortality up to 2.5 years after hospital discharge. Our findings suggest that when examining ICU delirium outcomes for research or quality improvement purposes, monitoring mortality up to 30 days after hospital discharge is likely sufficient. However, longer follow-up periods are needed when emergency department visits and hospital readmissions are also examined.

Our multicenter, population-based study, which followed nearly 6,000 ICU patients for 2.5 years , is the largest and longest follow-up of patients’ health and health resource use after ICU delirium. . Prior to this study, the literature on long-term mortality outcomes after ICU delirium comprised a total of 1,785 patients followed for durations between 6 and 12 months after ICU discharge. This literature was reviewed by Salluh and her colleagues, who identified four studies that reported conflicting results.

Subsyndromal delirium ( i.e., presenting with delirium symptoms that do not meet the diagnostic threshold) has received less attention in the literature. A systematic review by our team found an inconclusive association between subsyndromal delirium and mortality; three single-center studies (with sample sizes ranging from 162 to 537 patients) reported no association between subsyndromal delirium using the ICDSC and mortality in univariate and multivariable analyses. In the current study, a dose-response relationship between delirium severity and mortality was also not observed.

That is, the relationship between mortality and delirium was not different between patients who had shown subtensive delirium scores (i.e., ICDSC scores of 1 to 3) and patients who had shown delirium threshold scores (i.e. , ICDSC scores 4). However, up to 30 days after hospital discharge, both the number of days with delirium (i.e., 2 days more) and the percentage of time with delirium (i.e., between 25% and 75% of the hospital stay). ICU) were associated with increased mortality.

It appears that the amount of time spent with delirium (measured on both days and percentage of time) may portend a worse outcome than the severity of delirium in ICU patients who survive to hospital discharge.

Our research on the association between ICU delirium and subsequent health resource use in ICU patients after hospital discharge is new. An association was found between ICU delirium and subsequent ED visits, hospital readmissions, or mortality up to 30 days after hospital discharge. This suggests that the long-term burden of delirium is costly not only to the patient, but also to the healthcare system.

Our study had notable strengths , including the number of patients included and the duration of follow-up. Importantly, delirium was measured using the same validated instrument with the same time and frequency for all participants.

We were able to control for many potential confounders at the individual patient level and performed a propensity score matching analysis. Even with propensity score matching, residual confounding is possible, an inherent risk of observational studies. For example, given the nature of the data used, we were unable to control for the presence of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, which may be associated with both delirium and our outcomes of interest.

The linked administrative data used did not provide information on primary care visits or private supports (e.g., psychologist, family caregiver) used after hospital discharge. ICDSC assessment data was missing; however, the percentage of days without an ICDSC score was similar between the groups with and without a history of delirium.

The cause of death could not be determined for those who died within the first 30 days of hospital discharge, but proximity to ICU admission suggests that mortality may be modifiable by enacting specific discharge processes.

This multicenter, population-based study conducted in a single-payer health system allowed for comprehensive follow-up of all patients. Jurisdictions with different patient populations and health systems may have different experiences.

Conclusions:

ICU delirium is also associated with increased emergency department visits, hospital readmissions, or mortality after hospital discharge. Delirium is a common and life-threatening complication of critical illness that puts patients at risk for negative clinical outcomes and increased health resource use following an ICU admission. |