In the 1960s, surgery for hiatal hernia (HH) and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) was introduced, based on anatomical principles. The technical foundations of that surgery were essentially dictated by experience.

The following findings were reported: an adequate segment of the intra-abdominal esophagus should be enveloped by the stomach, the antireflux barrier is efficient if the fundoplication acts under abdominal pressure, and tension on the sutures should be minimal to avoid disruption [1-4]. .

Since the early use of open antireflux surgery, controversy has arisen between surgeons who treat patients using dedicated techniques in cases diagnosed with a shortened esophagus [5-7], and surgeons who deny the existence of a short esophagus. [8-10].

The clinical results achieved by both parties did not differ, regardless of the adoption of an open or minimally invasive technique.

In 2008, a multicenter study led our group to find that true short esophagus (CVD) was present in almost 20% of patients who were routinely sent to surgery for GERD and/or non-axial hiatal hernias. (HHNA); This study was based on intraoperative measurements, obtained in centimeters, of the distance between the gastric folds considered the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) and the apex of the diaphragm, after extensive mobilization of the intrathoracic esophagus[11].

Recently, in a study conducted to evaluate symptomatic recurrence in patients who underwent laparoscopic repair of large HH, the authors did not perform any esophageal lengthening procedure, because an adequate segment of abdominal esophagus was always achieved after extensive esophageal mobilization. ; concluded that the use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for the medical management of GERD can reduce peptic stricture formation, which is associated with short esophagus, and that esophageal lengthening procedures should probably not be applied more [12]. In that study, the position of the EGJ in relation to the diaphragmatic hiatus was evaluated subjectively.

Once again crucial questions related to the short esophagus debate were raised: is it possible that, without an objective evaluation of the position of the EGJ, the gastric fundus can be inadvertently coiled around the hypocardiac stomach, which acquires a tubular shape like consequence of progressive esophageal shortening [11,13], and can fundoplication of the gastric fundus around the stomach be inadvertently considered as a tubular esophagus and achieve good clinical results?

The authors of the present work studied a series of 311 patients who underwent surgery in the first instance for the therapy of GERD and/or NAFLD types II to IV [14,15], in the Division of Thoracic Surgery, in the period from 2004 to 2017. These patients had been recruited in a prospective research protocol, based on the intraoperative measurement of the distance between the GEJ and the apex of the diaphragmatic hiatus, to evaluate the eventual presence and degree of true esophageal shortening, evaluation preoperative radiology of the anatomy of the esophagogastric tract, and a clinical-radiological-endoscopic follow-up program.

The case series study was carried out to define the following: frequency of CVD; and long-term results of personalized surgery based on the treatment of CVD with the left laparoscopic-thoracoscopic Collis-Nissen (CN) operation [16], and with wrapping of the gastric fundus around the subcardial stomach (stomach fundoplication around the stomach [FEAE]; this last technique was deliberately performed in a series of patients with an increased risk for Collis gastroplasty.

| Methods |

All cases consecutively presented by surgical staff and residents to undergo a primary minimally invasive antireflux procedure for GERD or HH, during the period 2004 to 2017, were considered.

Surgical therapy was indicated according to current guidelines for the treatment of GERD [17]: presence of type II to IV HH [15] associated with severe symptoms, in the absence of absolute contraindications was per se an indication for surgery. [11,18]. Preoperatively, patients underwent symptomatic evaluation, serial barium, and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy.

Functional tests were performed according to clinical patterns. Postoperative morbidity and mortality within 90 days were calculated. Patients participated in a clinical follow-up program based on evaluation of symptoms, endoscopic findings, and serial barium, after 1, 3, and 5 years, and then every 3 years. The duration of follow-up was calculated from the day of surgery to the day of the last complete follow-up.

The results of the surgery were scored according to the data collected at the last follow-up. Reflux esophagitis (RE) was calculated according to the Los Angeles classification [19].

Symptoms of reflux (RS), dysphagia (DF), dyspepsia (DP), and degree of RE were scored with the validated modified Visick semiquantitative scales [20,21], and the overall assessment of surgical outcome resulted from the combination of the postoperative grades for the parameters of SR, DF, DP and ER [11,13].

Cases of HH recurrence diagnosed with serial barium, even those smaller than 2 cm, and those in which medical therapy (H2 blockers and/or PPI) was administered, continuously or temporarily, were classified as “result poor” in the absence of symptoms or esophagitis [11,13,22].

The barium series was performed pre- and postoperatively to define the relationship between the GEJ and the diaphragmatic hiatus, in upright and supine positions, and also the morphology and type of HH. The cases were distributed into 2 groups: axial HH (HAH) and non-axial HH (NAHH).

The HHA group included patients with normal GEJ, sliding HH, and the morphological intermediate steps of GEJ migration, hiatal insufficiency, and concentric HH (leading to an acquired short esophagus) [23]. The HHNA group included types II to III to IV of the Landrenau classification [14,24]. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed using standard methods [19].

> Intraoperative evaluation of the GEJ position

Endoscopic-laparoscopic procedures performed to measure the distance between the GEJ and the apex of the esophageal hiatus, and the extent of mobilization of the thoracic esophagus [11], have been described extensively elsewhere.

Briefly: the endoscope is introduced through the mouth into the esophagus and the tip is placed at the level of the gastric folds (GEU); the surgeon applies 2 clips to mark the position, and the distance between the EGJ and the apex of the hiatus is measured without any downward traction on the stomach, in the presence of an HPA, after a 360º mobilization of the EGJ (first measurement ), and after complete mobilization of the intrathoracic esophagus (second measurement) or, only in cases of HHNA, after complete mobilization (second measurement).

The measurement was considered positive (+) if a EGJ was above, and negative (-) if the junction was below the diaphragm. According to the final length of the intra-abdominal esophagus (second measurement), the cases were grouped into 3 classes: long (length >- 1.5 cm), short (length between 0 and 1.5 cm), and ultrashort (length > + 0.1cm).

It has clearly emerged from the literature that when an antireflux operation is performed, at least 2.5 cm of tubular esophagus should be below the hiatus in the absence of tension on the stomach [11,13,25-29].

When the authors of this work established the study protocol, with the objective of evaluating the frequency of “short” esophagus in GERD and HH, based on endoscopic-laparoscopic measurements [11], they arbitrarily categorized the cases as “ long” and “short”, when there was more or less than 1.5 cm of subdiaphragmatic esophagus, respectively, to avoid overestimating the frequency of CVD [11].

Recently, it was again stated that if there is not a minimum of 2 to 2.5 cm of tension-free intra-abdominal esophagus after maximal intrathoracic mobilization of the esophagus, a shortened esophagus is confirmed [30,31].

In the present study, the esophagus was defined as “ultra-short” when the EGJ was stuck over the hiatus (>+ 0.1 cm), because in that situation, the upper margin of the fundoplication is necessarily positioned below the EGJ in the abdomen or above the GEJ in the thorax.

> Surgery

The patients were placed on the operating table in the lithotomy position: when the barium series showed a GEJ in the intrathoracic position, the left pelvis and thorax were elevated 45º to the right, to facilitate access through a left thoracostomy along the of the posterior axillary line, in preparation for performing thoracoscopic Collis gastroplasty [11,13,15].

Isolation of the GEJ and the diaphragmatic pillars, identification of the vagus nerve and the hernial sac, and resection of the lipoma were performed. Mobilization of the thoracic esophagus was limited in cases of GEJ in the intra-abdominal position, and was maximal in cases of shortened esophagus, to descend the GEJ at or a few millimeters below the esophageal hiatus.

Laparoscopic lax Nissen (NL) was performed when the abdominal esophagus was more than 1.5 cm. A left laparo-thoracoscopic CN operation was adopted when the intra-abdominal esophagus was less than 1.5 cm.

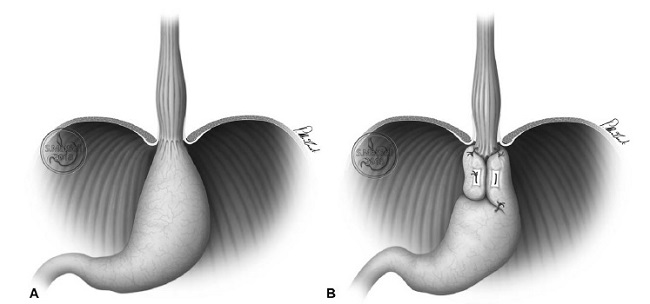

In a series of elderly patients affected with HH type III to IV who had significant comorbidity, and in whom the GEJ was still located at the level of the diaphragmatic hiatus after complete mobilization of the thoracic esophagus (abdominal esophageal length >+ 0 .1 cm) (Fig. 1A), the gastric fundus was deliberately wrapped around the stomach (FEAE) (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1: Stomach fundoplication around the stomach. In a series of elderly patients with HH type III or IV who had significant comorbidities, the EGJ was still located at the level of the diaphragmatic hiatus after mobilization of the esophageal hiatus (abdominal esophageal length = 0) (A), and the gastric fundus was wrapped around the stomach (FEAE) (B).

A Maloney plug was introduced by mouth into the stomach to perform NL and FEAE (54 Fr) and also CN (46 Fr). In the NL, CN and FEAE, the upper margin of the gastric fundoplication was fixed below the apex of the diaphragmatic hiatus via 2 lateral fundus-esophageal sutures, above or at the level of the EGJ (level of the clips), except in the cases of an ultrashort esophagus, in which case, despite maximum mobilization, the GEJ remained fixed above the hiatus.

> Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval

The present study was carried out in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki (1964, most recently amended in 2008) of the World Medical Association. The local JRI (IRST IRCCS Area Vasta Romagna) approved the use of the Division of Thoracic Surgery database for research purposes. Each patient provided written consent, and all patient information, including illustrations, was anonymized.

> Statistical analysis

Data are represented as the median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables, and as n (%) for categorical variables. The Chi-square test or Fisher’s test (expected number less than 5), and the Kruskal-Wallis or Mann-Whitney tests were used to analyze categorical and continuous variables, respectively.

The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare pre- and postoperative data. P values < 0.05 were considered significant. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

| Results |

Between 2004 and 2017, 311 patients (118 men; 37.9%; median age 57 years, IQR: 45-68) were referred for primary surgery for GERD and HH.

In the HHA group (170 patients), the intraoperative median distance between the EGJ and the apex of the diaphragm (– sign: EGJ below the hiatus; + sign: EGJ above the hiatus) was -1.5 cm in the first measurement (IQR: -2 to 0), while the second measurement (after esophageal mobilization) was -2.8 cm (IQR: -3 to -2.3).

In the HHNA group (141 patients), at the second measurement (the first measurement was not performed as explained in Methods), the median distance was -1.5 cm (IQR: -2.8 to 0) ( HHA vs HHNA; P < 0.0001). The median length of esophageal dissection was 8 cm (IQR: 5-10 cm) in the HHA group, and 11 cm (IQR: 9-12 cm) in the HHNA group ( P < 0.0001 ).

Data related to the intraoperative position of the EGJ after esophageal dissection for HHA and HHNA types of radiological classifications are reported elsewhere.

According to the final length of the intra-abdominal esophagus (second measurement), the cases were grouped into 3 classes: in 212 (68.17%) patients, the esophagus was long (length >- 1.5 cm); in 80 (25.73%) it was short (length between 0 and -1.5 cm); and in 19 patients (6.10%), it was ultrashort (length >+ 0.1 cm).

Mediastinal dissection was shorter in the long class (8 cm; IQR: 5-10) than in the short (11 cm; IQR: 10-12) and ultrashort (11 cm; IQR: 11-12) classes ( P < 0.0001).

Two hundred and thirteen patients (68.48%) underwent laparoscopic LN, and 82 patients (26.37%) underwent left thoraco-laparoscopic CN. A FEAE operation was performed in 16 patients (5.15%). The median length of the esophageal dissection performed in the LN was 8 cm (IQR: 5-10), that of the CN was 11 cm (IQR: 10-12), and that of the FEAE was 12 cm (IQR: 11-13) ( P < 0.0001).

In all cases classified as “long” or “short,” the upper margin of the Nissen fundoplateature was fixed above the native Z line, and below the apex of the diaphragmatic hiatus, regardless of the surgical technique.

In 19 cases of “ultrashort” esophagus, all of which were treated with the CN technique, the Nissen fundoplication was intra-abdominal, but the Z line remained above the upper margin of the fundoplication, across or slightly above the diaphragmatic hiatus.

In 11 cases (3.53%), including 7 LN and 4 CN, a conversion to an open approach was necessary (2004-2011). The conversion had no influence on the surgical technique. Postoperative mortality was 0.6% (2/311 patients). The two patients who died had undergone surgery for HHNA, one of them died from pulmonary embolism, and the other had a fistula from Collis gastroplasty in the early phase of minimally invasive surgery [15,16].

Postoperative complications occurred in 7.7% (24 of 311) of patients, including 2% in the NL group, 5.7% in the CN group, and 0% in the FEAE group [NL: 1 case of hemorrhagic shock due to stress-induced gastric ulcer, 2 cases due to hypercompetent fundoplication (surgical revision), and 7 cases of minor complications; CN: 4 cases due to intraoperative separation of the mechanical suture, 1 case of gastric perforation, 1 case of intrathoracic migration of the fundoplication, 1 case of Collis gastroplasty fistula, 1 case of pulmonary embolism, 1 case of intestinal obstruction, 1 case of intraoperative hemorrhage, and 8 cases of minor complications]. All major complications occurred before 2008 [15,16,32].

Postoperative follow-up (309 surviving patients) lasted between 12 and 144 months, with a median of 96 months (IQR: 60-144) in the NL group, 96 months (IQR: 36-144) in the CN group, and 54 months (IQR: 12-108) in the FEAE group ( P = 0.580).

HH relapse occurred in 10 of 309 cases (3.23%), including 5.12% in the HHA group, 9.70% in the HHNA group, 5 cases in the LN group (2.41%). , 4 cases in the CN group (4.91%), and 1 case in the FEAE group (6.31%) ( P = 0.433).}

Surgery significantly improved the parameters of the SR, DF, DP, and ER (pre vs. postoperative evaluation: P < 0.0001). The overall results were excellent in 141 patients (45.63%), good in 137 (44.34%), fair in 19 (6.14%), and poor in 12 (3.89%). Of the 12 patients who had poor outcomes, 7 underwent repeat surgery for recurrent HH and 5 were treated with PPIs.

No statistically significant differences were calculated between the results achieved in the groups with NL, CN and FEAE ( P = 0.938).

In 19 cases of “ultra-short” esophagus treated with the CN technique, in which the upper margin of the fundoplication did not cover the native Z line, the result was excellent in 31.58%, good in 57.90%, and poor (recurrence of reflux esophagitis) in 10.52%.

| Discussion |

The core of the controversy regarding the frequency and management of short esophagus has historically centered on the pre- and intraoperative diagnosis of this entity.

The radiological intrathoracic position of the GEJ and the presence of an esophageal peptic structure are considered the most common predictors of esophageal shortening [11,12,13,23,33].

In the era of open surgery, the intraoperative diagnosis of short esophagus was completely subjective, as was the tension necessary to traction or push down the EGJ [4,6,7,13,34].

Laparoscopy and video recordings allowed surgeons the opportunity to review and discuss their findings with others [28,32,33,35]. The concept of CVD was introduced following intraoperative measurements of the length of the abdominal esophagus [11,13,34,36,37]. However, during laparoscopy, surgeons may underestimate the condition of esophageal shortening. The presence of pneumoperitoneum elevates the diaphragm and may give a false impression that an adequate length of the intra-abdominal esophagus has been achieved[11,13].

In the case of long-lasting GERD, when a HH evolves from a type of axial sliding in the NAFLD types [6], the proximal stomach, drawn upward, acquires a funnel-like appearance, the serosa loses its brightness, and the wall thickens [11]. The tubularized proximal stomach is difficult to distinguish from the distal esophagus [11]. As a consequence, it is possible to lose the exact position of the CGU.

In the present study, when the endoscopic-laparoscopic method was used [11], the distance between the GEJ (gastric folds) and the apex of the diaphragmatic hiatus (in centimeters) was measured, before and after mobilization of the thoracic esophagus, in 311 patients undergoing primary minimally invasive surgery for GERD and HH. After maximal esophageal mobilization, CVD (an abdominal esophageal length < 1.5 cm without the application of downward tension) was detected in 99 of 311 cases (31.83%).

In relation to radiological predictors, CVD was diagnosed intraoperatively in 28 of 170 patients (16.47%) in the HHA group, and in 71 of 141 patients (50.35%) in the HHNA group. The frequency of CVD observed in this case series was therefore 13% higher than that observed in the 2008 study [11], potentially due to the higher number of cases of patients affected with NAFLD who were operated on in the series. of cases from 2004 to 2017 (45.33%), than in the 2008 series (18.88%) [11], which was itself a consequence of the aging of the population, and improvements in laparoscopic surgery, that allowed this surgery to be performed in older patients [38,39].

Peptic stenosis was present in the case series of GERD and NAHH with open and laparoscopic surgery reported in the literature, in which Collis gastroplasty was never performed, the gastric fundus was occasionally rolled around a funnel-shaped stomach or inverted tubular, which was mistakenly identified as the esophagus. However, long-term results were satisfactory in more than 85% of these case series, despite the fact that specific surgical techniques for the short esophagus were not adopted.

The empirical decision to wrap the gastric fundus around the proximal stomach (FEAE operation) in 16 elderly and frail patients, in whom CVD was identified during surgery for HHNA, originated from these considerations, and the results of the present series were as good as those obtained with the NC technique.

The literature data and the authors’ empirical experience with FEAE suggest that one of the pillars of antireflux surgery, the notion that the gastric fundus must be wrapped around a suitably long segment of tubular esophagus to achieve a fundoplication, should be discussed.

In this case series, the long-term results of NL, CN, and FEAE techniques were evaluated after a median follow-up of 96 months, and showed a similar satisfaction rate of more than 90%, with a frequency of 3.2% of recurrence, diagnosed radiologically, of HH (recurrences < 2 cm were included).

The authors believe that these results depend on a combination of clinical and surgical actions. The meticulous identification of the characteristics of the HH and the position of the GEJ with respect to the diaphragmatic hiatus in the standing position during the barium series allowed them to correctly plan the operation, including the appropriate position of the patient on the operating table, and the choice of the appropriate surgical team [13,16].

Clips marking the GEJ in relation to the hiatus guided the extent of esophageal mobilization and the decision to perform LN or CN or, more recently, FEAE. It is worth emphasizing that the EJ mark is a precious aid to surgeons in training.

When performing NL, CN or FEAE, the authors always respect the following principles of surgical physiology: they seek to achieve a complete absence of tension on the fundoplication; and the upper margin of the gastric fundoplication was always placed below the hiatus and, except in a minority of cases of “ultra-short” esophagus, above the 2 clips marking the GEJ, to avoid the formation of an acid pocket between the margin. superior of the fundoplication and the Z line, due to the production of acid secretion by the oxyntic cells of the hypocardial portion of the stomach [40].

In the 19 cases of ultrashort esophagus (6.1%), the Z line could not be located below the diaphragmatic hiatus, and the upper margin of the fundoplication could be positioned only 1 to 1.5 cm above the Z line. native. Two of the 19 patients (10.4%) complained of GERD symptoms and mild esophagitis in the absence of HH recurrence; both patients underwent successful medical therapy.

| Conclusions |

In conclusion, the authors demonstrated that in the PPI era, CVD is present in almost a third of cases undergoing routine surgery for GERD or NAHH; This is particularly common in NAFLD types II and IV, and is currently incorrectly called “giant paraesophageal hernia” [22].

Based on a critical interpretation of the literature, one could argue that hundreds of FEAE procedures have produced good clinical results, most likely without having consciously performed those procedures [12].

This speculation, when combined with the results they achieved in their FEAE series, should be enough to attract the interest of esophageal surgeons, including believers and non-believers, within the domain of the short esophagus, and justify – from an ethical – their participation in a multicenter randomized trial to compare the results of CN and FEAE in CVD cases, using the clinical and surgical methods that the authors adopted in the case series of the present study.