Clinical case A 35-year-old man with a history of inflammatory bowel disease presents to the emergency department (ED) with 2 days of abdominal pain. The pain is not localized, fluctuates in severity, and does not radiate. He reports worsening nausea, vomiting, and anorexia during this time. His last bowel movement was 2 days ago and he denies melena or hematochezia. His surgical history is significant for an appendectomy 5 years earlier and a cholecystectomy 2 years earlier. On examination, he is pale and diaphoretic, and his abdomen is diffusely tender with guarding. His vital signs are: heart rate 110, blood pressure 92/60, and temperature 99.6°F. Although you are concerned about a small bowel obstruction, the patient’s vital sign abnormalities are suspicious of a complicated obstruction. |

What are your next steps in care?

Perforated hollow viscus is the feared complication of intestinal obstruction, often resulting in sepsis and peritonitis, with a mortality rate reaching 30-50%. In particular, closed loop obstruction and strangulated obstructions have a higher risk of perforation.

There are many additional causes of intestinal perforation, including trauma, foreign body ingestion, diverticulitis, inflammatory bowel disease, steroid colitis, peptic ulcer, ischemia, and cancer. Although some causes are more insidious than others, their prognoses are similar.

Subsequently, early recognition of patients at high risk of perforation, immediate diagnosis, appropriate management and urgent surgical consultation are essential to prevent mortality in patients with perforated hollow viscus.

Risk factors, signs and symptoms

Patients with a history of abdominal surgery, radiation therapy, inflammatory bowel disease, or colon cancer are at increased risk of intestinal obstructions and perforations. Specifically, the development of adhesions, anatomical changes from previous surgeries, tumors, and any chronic inflammatory process make patients vulnerable to the development of complicated intestinal obstruction.

Additionally, intestinal perforations present similarly to intestinal obstructions, and patients often experience nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and bloating.

On physical examination , patients may have localized or diffuse abdominal tenderness, often with guarding, and may have overactive bowel sounds (in early-stage bowel obstruction) or decreased or absent bowel sounds (in late-stage bowel obstruction). Although classically associated with intestinal ischemia, disproportionate pain may be found on examination in patients with perforation.

Furthermore, signs of sepsis and peritonitis , including fever and leukocytosis, are not uncommon in patients with perforated viscera. However, hemodynamic instability, such as hypotension and tachycardia, may be absent and patients may appear deceptively stable in cases of late presentations.

Emergency study

Serum laboratory studies are generally not specific for patients with intestinal perforation, but may be a useful guide for resuscitation and optimization for surgical intervention. Patients should be considered unstable and in need of rapid resuscitation and probably emergency surgery if they have hemodynamic instability, pH <7.2, base excess < -8, or evidence of coagulopathy.

In a patient with a high suspicion of a perforated viscus, the first image obtained is a standing abdominal radiograph . Abdominal radiographs are good screening tools due to their easy accessibility and low cost. Although abdominal radiographs can quickly detect perforation, they only have a sensitivity of 66-85% and may be nonspecific.

The most common finding of perforated viscus on radiography is free air beneath the diaphragm , but this may be absent if there is minimal free air or if the patient is lying down (due to condition) rather than standing (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1 . A standing anteroposterior abdominal radiograph shows free air beneath the left hemidiaphragm, concerning for a hollow viscus injury (white arrow).

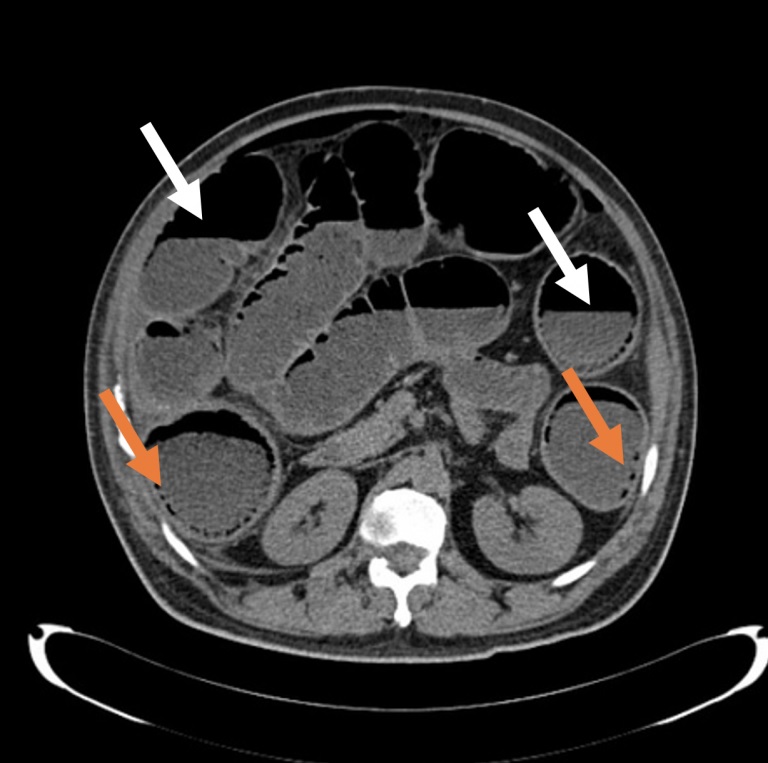

The sensitivity and specificity of computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis for intestinal obstruction approaches 100% but its ability to detect complications such as perforations is lower (Figure 2). Although considered the gold standard, CT only identifies the perforation site 82% to 90% of the time.

Subsequently, frequent reassessments, serial abdominal examinations, and consideration of the patient’s general clinical status are essential in patients with any obstructive process; New hemodynamic instability or peritonitis may suggest the development or worsening of intestinal perforation despite the lack of radiographic evidence on CT.

Additionally, up to 24% of small bowel obstructions require surgical intervention, either due to the development of complications or failure of medical treatment, and CT imaging in the ED can assist with surgical planning.

A CT scan with intravenous contrast is preferred to oral or rectal contrast, especially because patients with nausea and vomiting often cannot tolerate oral contrast. In the context of intestinal obstructions or perforations, the literature is scarce comparing the different contrast modalities (IV, oral or rectal). However, a meta-analysis showed no difference in perforation identification when comparing intravenous and oral contrast, although this study was performed in patients with perforation secondary to blunt abdominal trauma. If oral contrast is used, water-soluble contrast is preferred in case of contrast extravasation.

Although free air is highly suspicious for perforation, more subtle findings of intestinal perforation with or without concomitant free air include localized foci of extraluminal air, strands of mesenteric fat, thickening of the intestinal wall, extraluminal fluid, extraluminal abscess, contrast extravasation. oral and intestinal wall discontinuity. Additionally, free air can be found in the intraperitoneal, retroperitoneal, or extraperitoneal space, and its location further helps to elucidate the area of perforation along the intestine in unclear cases, which is useful for surgical planning.

Figure 2 . Axial section of a non-contrast abdominal CT showing air-fluid levels (white arrows) and multiple intramural air foci (orange arrows).

Differential diagnosis

Several conditions can mimic the radiographic findings of perforation on CT. Specifically, patients with recent abdominal surgery will have postoperative pneumoperitoneum for an average of two weeks; Infections such as emphysematous pyelonephritis or emphysematous cholecystitis will have air foci; barotrauma, pneumothorax, or pneumomediastinum can draw air between the abdominal wall and peritoneum.

While this list of differential diagnoses is not inclusive, it highlights the need for an accurate history and physical examination to help correlate clinical suspicion with radiographic data.

Alternative imaging modalities include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which is generally more expensive and less available in the ED, and bedside ultrasound. Ultrasound is user dependent but has a specificity of 84-100% and a sensitivity of 83-97% for recognizing small bowel obstructions (SBO). However, complications such as perforation may be more difficult to identify on ultrasound.

Management

In uncomplicated small bowel obstructions (SBO), medical treatment including antiemetics, analgesics, electrolyte optimization, and bowel rest can often resolve the obstruction. Additionally, a nasogastric (NG) tube can decompress the stomach and reduce the patient’s symptoms. There has been much debate about the usefulness of NG tubes in SBO, but there is a paucity of data regarding NG tubes for intestinal obstruction or perforation. Insertion of NG tubes for symptomatic patients, particularly those with active vomiting and abdominal distension, may be a reasonable strategy.

In any patient with an obstructive process, fluid replacement with balanced crystalloids such as lactated Ringer’s (LR), correction of acidosis if present, control of pain and nausea, and optimization of electrolytes are necessary. Unfortunately, data on specific fluid administration (liberal, restrictive, or goal-directed) are limited, especially in patients undergoing abdominal surgery, and the patient’s clinical status should dictate fluid management.

However, unlike uncomplicated obstructions, intestinal perforation requires urgent surgical consultation for surgical repair.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics should also be started early, ideally covering Gram-negative and anaerobic bacteria. A lesion of any size in the intestinal mucosa (edema, perforation, ischemia) can cause the translocation of intestinal microorganisms and, in the case of large defects, a frank fecal spill into the peritoneum.

Therefore, even if a patient does not appear septic, prophylactic antibiotic coverage of gram-negative and anaerobic bacteria should be administered. Specifically, physicians must cover Enterobacteriaceae, Klebsiella, and Enterococcus, with additional coverage for Staphylococcus (including MRSA) and Pseudomonas in patients with recent instrumentation or hospitalization. Strategies include piperacillin-tazobactam 4.5 g as a loading dose with 3.375 g given every 8 hours, ertapenem 1 g every 24 hours or metronidazole 1 g every 12 hours + ciprofloxacin 400 mg every 8 hours. Addition of vancomycin 20 mg/kg can be added to cover MRSA, if necessary.

Resolution of the case

The patient’s rectal temperature revealed a fever of 38.5 degrees. After receiving 2 liters of LR, as well as acetaminophen and morphine, the patient’s vital signs improve to HR 95, BP 115/70, and temperature 36.5°.

Upon recognition of sepsis, empirical piperacillin-tazobactam is started and blood cultures and laboratory tests are drawn, which return with a white blood cell count of 22,000.

Because the patient is too weak to stand, his supine chest and abdominal radiographs are unremarkable, but subsequent CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast shows a perforated small bowel obstruction.

Surgery is consulted and the patient is admitted for surgical repair of his intestinal perforation in the operating room.

Key points

|