Presentation of a case A 67-year-old man with a history of atrial fibrillation treated with edoxaban that had begun to worsen 4 weeks before the consultation, with difficulty breathing. He is a smoker, consuming 40 packs a year. He has had previous exposure to asbestos from his work as a builder. The doctor requested a chest x-ray showing a unilateral (right) pleural effusion of moderate size. |

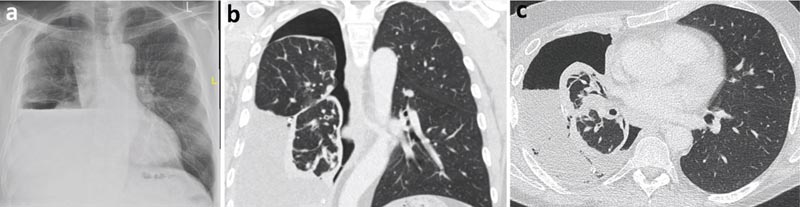

Figure 1: Initial chest x-ray

What is the cause of this patient’s symptoms?

Some patients with pleural effusion may have minimal symptoms, but others may experience shortness of breath with little ability to exercise. This may be associated with normal or reduced oxygen saturation.

The physiology of dyspnea associated with pleural effusion is not well understood, but reduced ventilatory capacity and gas exchange, as well as abnormal movement of respiratory muscles, with reduced rib cage expansion, are likely to contribute. and splinting of the diaphragm.

What is the cause of pleural effusion?

Although the etiology of this patient’s pleural effusion is unknown, certain risk factors (including a history of smoking and exposure to asbestos) make the authors suspect a malignant pleural effusion in the first place. Ipsilateral chest pain may suggest malignant mesothelioma.

Pleural effusions are classified by their biochemical properties into exudates and transudates, but they can also be due to blood, pus, and chyle.

| Common Causes of Pleural Exudates and Transudates | |

Exudates Infection (bacterial, tuberculosis, and parasitic) Malignancy (mesothelioma, lung and breast cancer) Connective tissue disease (rheumatoid arthritis) Drug-induced inflammatory conditions (e.g., pulmonary infarction) Acute pancreatitis Chylothorax | Transudates Congestive heart failure Hepatic cirrhosis Chronic renal failure Hypoalbuminemia

|

Application of Light’s criteria may be useful in diagnosing an exudative effusion. However, 25% of transudates are misclassified as exudates and therefore it may be necessary to calculate the serum/pleural fluid albumin gradient, in order to avoid misdiagnosis.

Light’s criteria for exudative effusions Exudative effusions will have one or more of the following. > Pleural fluid protein/serum protein > 0.5. > LDH in pleural fluid / LDH in serum > 0.6. > Pleural fluid LDH > 2/3 of the upper limit of serum LDH |

| LDH: lactic dehydrogenase |

Exudative effusions are commonly caused by infections, malignancy, and inflammatory disorders, such as in rheumatoid arthritis. The most common malignant pleural effusions are those caused by lung and breast neoplasms, affecting up to 15% of cancer patients.

Transudate effusions, often bilateral, are usually caused by an imbalance between oncotic and hydrostatic pressures and are associated with cardiac, renal, or hepatic failure. Nonmalignant pleural effusions have been shown to have high annual mortality rates. Up to 30% of pleural effusions receive a multifactorial etiological diagnosis, therefore it is essential to have an accurate etiological diagnosis, as this will affect the choice of subsequent management.

A week later, he went to see a pulmonologist .

What is the most appropriate intervention?

In patients with suspected undiagnosed malignant effusion, a pleural aspiration can be performed while planning the course of action to follow, and what the useful intervention will be if the pleural fluid has malignant cells.

Edoxaban was discontinued for 48 hours before the procedure due to the risk of bleeding. After aspiration of 1 liter of pleural fluid, symptoms improved. The liquid was sent to the laboratory for biochemical (proteins, lactic dehydrogenase and glucose), microbiological and cytological analysis.

Intervention in pleural effusions can be performed for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. If the cause of the spill is unclear, a decision must be made on the most appropriate intervention, based on:

- The symptoms and/or clinical status of the patient.

- The etiology of the pleural effusion (if established)

- If further studies are necessary.

It should be noted that when performing pleural procedures for fluid removal it is essential to use immediate or real-time thoracic ultrasound . In 2008, the WHO warned of cases of death and serious harm caused by the insertion of a chest drain.

The British Thoracic Society (BTS) recently published thoracic ultrasound training standards for clinicians also dealing with the management of acute respiratory problems and performing emergency thoracic ultrasounds.

On the other hand, non-urgent procedures are contraindicated in the presence of coagulopathy . That BTS advises avoiding procedures in anticoagulated patients until the INR (international normalized ratio) is <1.5.

As for direct oral anticoagulants , they should be discontinued for 24 to 48 hours, depending on renal function and bleeding risk, while therapeutic low molecular weight heparin should also be discontinued for 24 hours.

Diagnostic thoracentesis

In most patients, the appropriate initial investigation is diagnostic thoracentesis.

Performed under ultrasound guidance, it is a minimally invasive procedure that allows the analysis of pleural fluid for diagnostic purposes. In malignant pleural effusions, pleural fluid cytology has variable diagnostic sensitivity. Previous BTS guidelines cited a diagnostic accuracy of 60%, but a recent study found that the sensitivity of cytology is approximately 45% to 55%.

The diagnostic sensitivity is greater in the presence of ovarian, breast and lung cancers (adenocarcinoma), 95%, 71% and 82%, respectively. In malignant mesothelioma , previous studies showed a diagnostic sensitivity between 16% and 73%. Although recently Arnold et al showed that the sensitivity was closer to 6%.

Furthermore, while the BTS guidelines advise that a minimum volume of 20-40 mL of pleural fluid is required to make the diagnosis, it has been proven that a minimum volume of 75 mL increases diagnostic sensitivity.

Even if a diagnosis is obtained, the material may not always be sufficient for molecular markers/ driver mutations , which will aid in decision making for immunotherapy or molecular targeted therapy.

Therapeutic thoracentesis

Therapeutic thoracentesis performed under ultrasound

The guideline allows for analysis of pleural fluid to aid diagnosis, as well as removal of a larger volume of pleural fluid for symptomatic relief. The procedure avoids the insertion of a chest drain and can therefore be performed on an outpatient basis to avoid hospitalization. If pleural fluid cytology is nondiagnostic, residual pleural fluid requires a major procedure, including image-guided pleural biopsy or thoracoscopy with local anesthetic.

Intercostal thoracic drainage

Intercostal chest drain insertion (ITD) performed under ultrasound guidance allows for analysis of pleural fluid, complete drainage of pleural effusion, and administration of intrapleural agents, if required.

Pleurodesis is commonly induced by administering a talcum suspension through the intercostal chest drain to prevent recurrence of probable or confirmed malignant pleural effusion. Talcum slurry pleurodesis has a 24% failure rate. This option may be appropriate for symptomatic patients with large-volume pleural effusions who are non-ambulatory, frail, in whom other invasive testing may not be appropriate, or when the etiology of the effusion is known.

The BTS guideline recommends caution if >1.5 L of pleural fluid is removed on a single occasion due to the risk of developing reexpansion pulmonary edema, a condition that can cause cough, chest pain, and even cardiovascular instability and collapse. .

Another alert highlights the need to guarantee controlled drainage to avoid this possible complication. Clinicians should note that interventions for pleural effusion, despite the use of thoracic ultrasound, should be avoided after hours, unless it is an emergency, to minimize errors and complications.

A chest x-ray following therapeutic thoracentesis revealed hydropneumothorax formation, raising the possibility of a nonexpandable lung. Fluid analysis of the exudative pleural effusion was requested (protein 40 g/l and LDH 620 IU).

Cytology revealed a lymphocytic effusion without malignant cells. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest demonstrated a parietal pleural cortex predominantly encompassing the right lower lobe, probably causing a nonexpandable lung.

Figure 2

a) Post-thoracentesis chest x-ray with hydropneumothorax (air and fluid in the pleural cavity).

b) Chest CT, coronal view.

c) Chest CT, axial view.

What is the most appropriate next intervention?

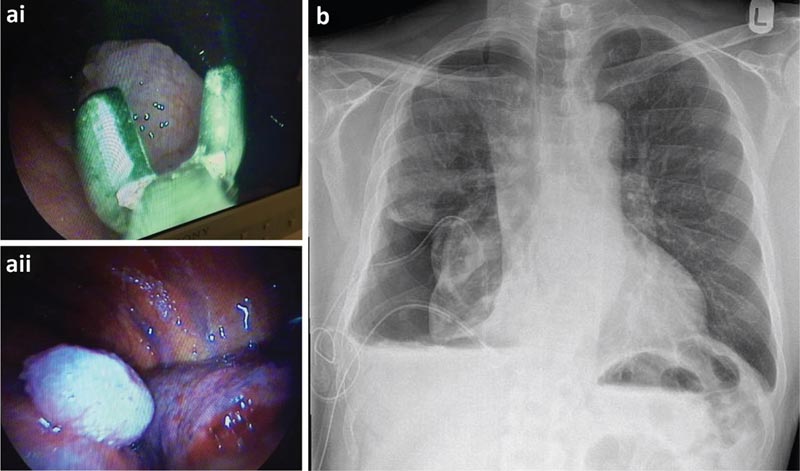

As pleural fluid cytology was not diagnostic, the patient underwent thoracoscopy under local anesthesia and moderate sedation (TAS), also known as medical thoracoscopy or pleuroscopy. It is a medical procedure performed by pulmonologists, which includes internal examination, biopsy and/or administration of therapeutic agents into the pleural cavity.

Its main indication is the study of exudative effusions of unknown etiology, particularly when there is no pleural target for taking the CT-guided biopsy sample and pleurodesis. It is also useful for the diagnosis of pleural TB combined with sampling for culture and histology, with a sensitivity of up to 100%, depending on the prevalence.

The effectiveness of TAS in the diagnosis of malignancy is as high as that of biopsy in video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). This biopsy is generally done under general anesthesia and one-lung ventilation. TAS can also be used for therapeutic indications. Talcum powder pleurodesis can be used if the pleura appears abnormal on direct inspection. It is as effective as talcum slurry in achieving pleurodesis more effectively in patients with lung or breast cancer.

TAS may also be useful in pleural infections, allowing division of septa and adhesions, and helping to place chest drainage more accurately.

TAS can be performed using a semi-rigid thoracoscope that is similar in design to a flexible video bronchoscope or a rigid thoracoscope; both provide similar diagnostic accuracy.

The patient underwent TAS which showed a large number of nodules over the visceral and parietal pleurae. It was decided to insert an indwelling pleural catheter (PPC) at the time of thoracoscopy for a probable non-expandable lung.

a) Biopsies of parietal pleura taken during thoracoscopy and thoracoscopic view of a malignant nodule. b) Post-thoracoscopic chest x-ray.

What is the role of indwelling pleural catheters (PPC)?

CPPs are considered an important tool in the management of pleural effusions. A CPP is a soft, flexible, silicone tube with multiple fenestrations. Before entering the pleural cavity, it is introduced into a subcutaneous tunnel.

CPPs were initially designed as a second-line treatment for patients with malignant pleural effusion with nonexpandable lung or failed pleurodesis, and may remain in the pleural cavity and outlive the patient.

Nonexpandable lung (or trapped lung) occurs when the lung cannot expand after drainage of pleural fluid, either due to endobronchial obstruction or coverage of the visceral pleura by tumor.

The role of CPPs in the treatment of pleural effusion experienced a paradigm shift following the publication of the TIME2 and AMPLE trials supporting their use as first-line treatment. They are safe and reduce the length of hospital stay in patients who traditionally would have required prolonged and often multiple hospitalizations.

CPPs have changed the management of pleural effusions to a more outpatient setting. Drainage of CPPs is assisted by nursing staff, but patients can be advised and encouraged to drain and manipulate their own devices.

The frequency of drainage is commonly 2-3 times/week, but can be adapted to the patient’s needs. If the goal is palliative, then drainage may be guided by symptoms. However, if the goal is to achieve rapid pleurodesis with subsequent drainage removal then daily drainage may lead to a higher rate of autopleurodesis and a faster time to CPP removal. Autopleurodesis is defined as spontaneous pleurodesis without the use of a chemical agent.

Although it is not the objective of CPP insertion, it could be observed in up to 51% of patients with malignant pleural effusion. Furthermore, aggressive drainage with talc administration through the CPP may result in 2-fold higher rates of pleurodesis compared with insertion of the CPP alone. The role of CPPs in non-malignant pleural effusions is less defined and must be tailored to the patient.

The first randomized trial of refractory pleural transudates concluded that CPPs did not offer superior control of dyspnoea compared with therapeutic thoracentesis. In that trial, the CPP arm experienced more adverse events. In hepatic hydrothorax, a PPC can be placed with palliative intent, for patients who have exhausted medical management and are not candidates for transplant, or for those who require bridging treatment to manage the effusion before transplant.

As the use of CPPs becomes more widespread, physicians may encounter more complications related to their placement, which may occur in 10%-20% of patients. Pleural infection, catheter obstruction, and symptomatic loculations tend to be the most common and can be treated. In oncology patients, there is good evidence that there is no increased risk of CPP-related infection due to chemotherapy or immunosuppression.

Pleural biopsies revealed malignant epithelioid mesothelioma. After discussion by a multidisciplinary team, the patient was referred to oncology for treatment. The patient continued to drain his IPC 3 times/week and subsequently achieved autopleurodesis. The CPP was removed shortly afterward.

Summary Investigation of a unilateral pleural effusion is a common clinical scenario faced by both general practitioners and pulmonologists. With the high prevalence of malignant pleural effusions associated with lung cancer and other advanced-stage neoplasms, it is increasingly important to perform the correct and most useful studies. This is particularly important in relation to advances in oncological therapy, whereby diagnosis based solely on pleural cytology may be insufficient, and complementary pleural histology may provide additional information (including molecular analysis) to guide treatment. As with many aspects of modern healthcare, the investigation and management of patients with pleural effusions is increasingly being managed on an outpatient basis. With the adoption of same-day emergency services and pleural clinics in many hospitals, this provides patients with streamlined, efficient and effective care. This has been particularly relevant during the COVID-19 pandemic and reduces the cost and risk of hospital-associated infection for the patient. This, along with devices (such as the CPP) that have been designed specifically for patients who wish to remain at home, has allowed for the emergence of a modern approach to medicine. |